Nazi collaborator monuments in Germany

The country where Adolf Hitler came to power has a mixed history on Holocaust memory

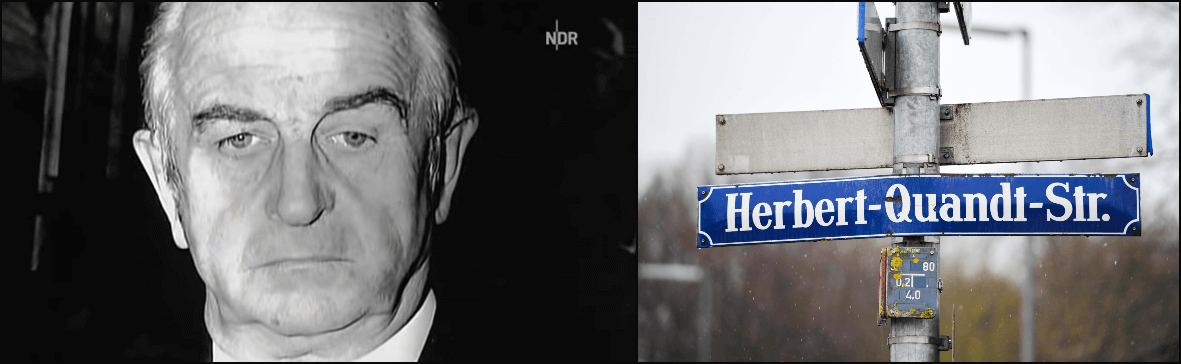

Left: Herbert Quandt (Screenshot from “The Silence of the Quandts,” YouTube). Right: Herbert Quandt Street, Munich (Alessandra Schellnegger/alessandraschellnegger.com). Image by Forward collage

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email editorial@forward.com, subject line: Nazi monument project.

Note: In addition to the examples listed here, Germany has hundreds of streets and monuments to individuals who were antisemites and/or Nazi Party members but did not fully meet the criteria for inclusion in this project. They are listed at the end of this article.

Berlin and 17 other locales – a bust of Ferdinand Sauerbruch (1875–1951), a pioneer in surgery who was head of the medicine branch of Nazi Germany’s Reich Research Council, the body responsible for funding and authorizing experiments on concentration camp inmates. In that capacity, Sauerbruch was aware of and approved mustard gas experiments conducted on concentration camp prisoners by the infamous August Hirt. Originally, Sauerbruch welcomed the Nazi rise to power and received the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Swords, the Third Reich’s highest honor. However, he’s also said to have attempted to end the Nazi euthanasia program – certainly a brave action under the Third Reich – and supported victims of Hitler’s regime.

This deeply ambivalent figure also has streets in Alfeld, Altrip, Bad Berleburg, Blaustein, Cottbus, Greifswald, Gunzenhausen, Homberg (Efze), Itzehoe, Koblenz, Lübbecke, Lünen, Mölln (Schleswig-Holstein), Ratzeburg, Töging am Inn and Ulm as well as a school in Großröhrsdorf. See nuanced Annals of Surgery article on Sauerbruch’s legacy.

Note: The street in Blaustein was added to this entry January 2023.

Wolfsburg and 62 other locations – A bust and street honoring Ferdinand Porsche (1875–1951), designer of the eponymous car line and the Volkswagen Beetle. Porsche was a member of the Nazi Party and the SS, recipient of the War Merit Cross, and Hitler’s favorite engineer. Above left, Hitler speaks at a ceremony for laying the foundation stone of the Wolfsburg factory, May 26, 1938. Porsche is on the far right.

Porsche was far more than Hitler’s car dealer – he designed weapons such as the Tiger tank for the Nazis. Most disturbingly, his plants used slave labor including conscripts from Eastern Europe and concentration camp prisoners. The Volkswagen factory in Wolfsburg is infamous for murdering up to 400 infants – the children of their slave laborers.

Porsche has another bust in Kaufbeuren; a bust and information plaque (at the Porsche Museum) and a school in Stuttgart; a bust in the Prototype Museum in Hamburg; a school in Weissach; and streets in Althengstett, Bad Kreuznach, Bad Wörishofen, Balingen, Besigheim, Bischofswiesen, Bonn, Bremen, Bretzfeld, Buchloe, Cloppenburg, Cologne, Crailsheim, Denzlingen, Dettingen an der Iller, Ellwangen, Emden, Erkelenz, Espelkamp, Essingen (Baden-Württemberg), Ettlingen, Frankfurt, Freudenstadt, Friedrichshafen, Garching an der Alz, Gattendorf, Gera, Giengen, Gilching, Göttingen, Grünstadt, Günzburg, Gütersloh, Hanover, Heinsberg, Hilden, Holzwickede, Kaisersesch, Leimen (Baden-Württemberg), Lippstadt, Magstadt, Murr, Nagold, Nufringen, Offenbach, Reiskirchen, Reutlingen, Rodgau, Rostock, Saterland, Schifferstadt, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Seligenstadt, Stade, Stephanskirchen, Tarp, Vöhringen (Baden-Württemberg) and Weil der Stadt. Note: Streets in Erkelenz, Freudenstadt and Tarp were added to this list in October 2022; streets in Dettingen an der Iller, Kaisersesch and Rostock were added January 2023.

See Volkswagen’s history page with photographs, Jewish Virtual Library for list of German companies which used slave labor and coverage from the New York Times and Time. For a history of how German car manufacturers have whitewashed their wealth, see “Nazi Billionaires” by David De Jong (his essay in the New York Times here). See the Austria, Czech Republic and U.S. sections for more Porsche honors.

Greifswald and three other locales – The University of Greifswald’s Alfried Krupp Institute for Advanced Study, named after Alfried Krupp (1907–1967). An industrial mogul and convicted war criminal, Krupp not only armed Nazi Germany but used 100,000 slaves. These were concentration camp inmates and prisoners of war, including children. Estimates vary as to how many slaves were worked to death by Krupp; what’s clear is that they labored in abhorrent and deadly conditions.

Krupp’s role in the Holocaust’s labor system was egregious enough to warrant its own Nuremberg tribunal. Among his company’s assets was a large factory staffed with Auschwitz prisoners. “When they could no longer work, the SS took them away to be gassed,” is how a former Nuremberg prosecutor described the factories run by Krupp and others.

Krupp’s punishment for being convicted of crimes against humanity was a 12 year sentence; he served a total of six (including pre-trial confinement) before his sentence was commuted by John McCloy, the U.S. High Commissioner for Germany notorious for freeing dozens of Nazis. McCloy even ordered the restitution of Krupp’s assets that had been seized by the court. Krupp admitted no guilt, telling the court he was “only doing my duty.”

Krupp has been rebranded as a civic benefactor in the usual fashion: pumping money into public works that bear his name. Krupp’s honors include a bust in his Greifswald institute; a street, hospital (with bust), concert hall (with bust), school, nursing home and bust (in the Villa Hügel Krupp family museum) in Essen; the Alfried Krupp Student Laboratory for Science in Ruhr University Bochum; and a residential college in Jacobs University in Bremen.

Below left, Krupp testifies at his war crimes trial, 1947; below right, prisoners building Krupp’s factory at Auschwitz. See essay on the whitewashing of Krupp, New Eastern Europe; teaching information at Facing History; and paper and book by Stanley Goldman, the son of a concentration camp survivor who was forced to work for Krupp.

***

Burbach (North Rhine-Westphalia) and four other locales – A street named for Friedrich Flick (1883–1972), another industrial titan who powered the Nazi war machine and made massive profits using slave labor. Flick was part of Freundeskreis Himmler (“Himmler’s Circle of Friends”), a group of industrial magnates intimately connected to the Third Reich: these figures financially buttressed the Nazi regime, reaping massive profits in return. According to Nuremberg prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz, Flick “met regularly with Himmler.” His steel empire was built on the expropriation of Jewish businesses – the Nazi-sanctioned seizure and sale of stolen Jewish property – as well as the use of tens of thousands of slave laborers. As many as 40,000 slaves were killed working for Flick.

After the war, Flick and his nephew Bernhard Weiss (1904–1973) were found guilty of crimes against humanity and war crimes. Flick’s penalty was seven years; he served a total of five (including pre-trial confinement) before being released by John McCloy (see Alfried Krupp entry above). Weiss was sentenced to two and a half years and served around one. Within several years after his release, Flick once again became one of the richest (and likely the richest) men in Germany.

Above left, Freundeskreis Himmler members visit Dachau concentration camp, 1936. Flick is fourth from left, with cane. On the far left is SS head Heinrich Himmler, one of the principal architects of the Holocaust. Above right, Flick at his war crimes trial sentencing, Nuremberg 1947. Flick has additional streets in Maxhütte-Haidhof, Schwandorf and Teublitz; Weiss has a square in Hilchenbach.

Munich and five other locales – Industrial magnate Herbert Quandt (1910–1982) and his father Günther ran the AFA battery company. Herbert Quandt was AFA’s director of personnel and manager of Petrix GmbH, the firm’s Berlin subsidiary. The family’s wealth grew through appropriation of Jewish assets and the use of 50,000 slave laborers.

The conditions at Quandts’ plants, where concentration camp inmates were exposed to acids and poisonous gases with no protection and no drinking water, were so lethal that the company lost an average of 80 slaves a month, with a slave expected to live no more than six months. The Hanover plant had a gallows.

After the war, the Quandts largely avoided even nominal attention to their crimes. A Nuremberg prosecutor later stated that had his deeds been known, Günther Quandt would’ve been in the dock for crimes against humanity.

The Quandt empire, which went on to buy BMW, acknowledged little of this until the airing of a 2007 documentary “The Silence of the Quandts”. Herbert Quandt has streets in Munich (Google translation here), Dingolfing, Göttingen, Hildesheim and Regensburg as well as a school in Pritzwalk. BMW also has the BMW Foundation Herbert Quandt which, according to its mission, “promotes responsible leadership.”

Espelkamp – When it comes to the intersection of industry and the Holocaust, few corporations have as deep a connection as IG Farben. The chemical conglomerate got slave labor from 30,000 Auschwitz inmates, conducted horrific medical experiments on prisoners and manufactured Zyklon B, the gas used to carry out the genocide. Nuremberg held a separate trial for IG Farben; one of the men convicted was Max Ilgner (1899–1966), IG Farben board member and Wehrwirtschaftsführer (Third Reich military economic leader). Ilgner was sentenced to three years, but served less than one. Upon his release he got a job organizing the creation of Espelkamp, a town for displaced persons and refugees, then became a lobbyist and the CEO of a chemical company.

Espelkamp has a street for Ilgner; in 2020, the town refused to rename it. (Google translation here). Above right, IG Farben plant at Auschwitz, 1941.

Hanover – A fountain and street dedicated to Fritz Beindorff (1860–1944), owner of the writing materials manufacturer Pelikan. In 1932, Beindorff signed an infamous letter from German industrial magnates urging the government to make Hitler chancellor. After the Nazis took power, Pelikan not only received slave labor but housed at least one work education camp. These brutal camps run by the Gestapo (Third Reich secret police) imprisoned laborers who had broken regulations or were deemed uncooperative; according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the death rates in these camps approximated that of concentration camps. Below, the Pelikan plant festooned with swastikas for its 100th anniversary, 1938.

In 2014, Hanover commissioned a report regarding landmarks named after Nazis; Beindorff’s street was recommended for renaming. The city refused to change the name but pledged to create a memorial plaque for the slaves of Beindorff’s plant. As of June 2021, no plaque has been installed.

See summary of report (Google translation here), coverage of debate over Beindorff in Hannoversche Allgemeiner Zeitung (Google translation here and here) and photos and summary of Pelikan’s Nazi past on Joshua Danley’s blog.

***

Hanover and four other locales – In 2019, the heiress to the Bahlsen food company triggered international headlines after indignantly claiming her family – which used slaves during WWII – “did nothing wrong” and “treated them well.” (She later issued an apology statement for her comments).

During WWII, the corporation was run by the brothers Werner, Klaus and Hans Bahlsen. All three were Nazi Party members and two (Werner and Klaus) funded the SS. The Bahlsen empire used 2,150 slaves in a biscuit factory it took over in Nazi-occupied Kyiv. It also “employed” an additional 700 slaves in Germany, mainly Eastern European women forcibly sent to toil in its Hanover plant.

In 2000, Frankfurter Rundschau published a firsthand account from one of the women taken from the Kyiv factory to Hanover. She said: “In August 1942, after the end of the shift, we saw that the building was surrounded by soldiers with sheepdogs. Nobody was let through the gate. The youngest, most powerful of our ranks were sorted out – 260 people. Without explaining anything, we were loaded onto trucks and taken to the train station, where we were put into freight wagons. The head of this shameful operation was our boss himself – Werner Bahlsen. Terrible crying and screaming began. And suddenly music boomed from the speakers. Our mothers and relatives came running to the train station, someone had managed to notify them that we were being taken away. They tried to give us food and clothes, but the soldiers pushed them away with rifle butts.” (Excerpt quoted in Handelsblatt, Google translation here.)

In 1972, Klaus Bahlsen established a foundation that lavished Hanover with public projects, pouring millions into the city (Google translation here); Bahlsen’s biography on the foundation website says nothing about his Nazi background or that his wealth was gained from slave labor (Google translation here). The foundation’s description on the official Hanover city website is similarly silent on this (Google translation here).

Hanover has a fountain (detail, top right), nursing home, cancer center, dormitory, bridge and walkway named after him or him and his wife. Outside of Hanover, Bahlsen’s foundation funded the Klaus Bahlsen Tower, an observation tower for watching sea eagles in Gartow; the Klaus Bahlsen Haus nutrition center at Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences in Wallenhorst; the Klaus Bahlsen Center for Sustainable Nutrition in Aurich (built in partnership with the city of Aurich); and the Klaus Bahlsen Haus information center in Usedom. Note: The Hanover cancer center was added to this entry January 2023.

See coverage in Der Spiegel, which unearthed the extent of Bahlsen’s ties to the Third Reich (Google translation here), Wolfsburger Allgemeine Zeitung (Google translation here) and investigation by FragDenStaat (Google translation here). Above left, Ukrainian women being forcibly taken from Kyiv to work in Germany.

Hamburg and Henstedt-Ulzburg – In 2017, Hamburg issued a report of landmarks honoring Nazis. On it are a street and high school named for Kurt Körber (1909–1992), technical director of Universelle-Werke Dresden, a weapons manufacturer which used over 3,000 slave workers. According to the report, Körber, a Nazi Party member, was involved in establishing a slave labor camp for Universelle. Hitler’s regime also gave Universelle 700–800 women workers from the Ravensbrück concentration camp complex.

After the war, Körber, much like the other Nazi Party members and war profiteers in this section, established a foundation and spent millions on public projects. This includes the Haus im Park senior art center and event space, which displays a bust and a plaque with a quote by Körber. Another bust sits in the Körber foundation’s current headquarters while the KörberHaus cultural center is set to open in 2022; it’s unclear what, if any, monuments to Körber it’ll have.

Körber’s street in Hamburg was named in 1998; the high school in 2007. They’re part of a pattern which has seen numerous German municipalities proactively and consciously name streets and schools for Nazis over the past 25 years. The fact that such whitewashing is taking place even in Germany shows the degradation of Holocaust remembrance. The school’s profile of Körber mentions nothing about his Nazi membership or use of slaves (Google translation here). See summary of report (Google translation here). Below, slave labor from inmates in Ravensbrück.

Update (October 2022): There is also a street named for Körber in Henstedt-Ulzburg, a town of about 25,000 people about 15 miles north of Hamburg.

***

Ladenburg – A street for Albert Reimann Jr. (1898–1954), antisemite and staunch Nazi supporter whose industrial chemical business used slave labor. Reimann Jr. along with his father, Albert Reimann Sr., began supporting the Nazis in the early 1930’s. In 1937, Reimann Jr. assured Heinrich Himmler the family were “absolute followers of racial theory” (Google translation here). The company’s female slaves were physically and sexually abused to such an extent that the local Nazi office stepped in to admonish the company. Perversely, both Reimanns attempted to paint themselves as anti-Nazi activists after the war.

In 2016, the Reimanns – one of the wealthiest families in the world whose conglomerate owns Panera Bread and Krispy Kreme, among others – commissioned a report about their wartime past. “We were ashamed and white as sheets. There is nothing to gloss over. Their crimes are disgusting,” said the family spokesperson, a rare admission made without the typical caveats German dynasties employ to minimize their crimes. Above right, concentration camp prisoners at forced labor, Dachau, May 24, 1933.

Neuhof (Hesse) – A street for August Rosterg (1870–1945), another industrialist who signed the 1932 letter calling for Hitler to be made chancellor (see Fritz Beindorff entry above). He was also a member of the Freundeskreis Himmler (see Dachau photo in Friedrich Flick entry above; Rosterg is fifth from left, next to Flick). Rosterg capitalized on the Nazi takeover – he ran Wintershall, a potash and oil empire that seized industrial assets stolen from Jews and used slave labor, including 1,360 inmates from the Buchenwald concentration camp. Above right, Buchenwald inmates building the Weimar-Buchenwald rail line, 1943.

Bad Soden — The spa town on the outskirts of Frankfurt has a conference center named for Nazi Party member and war profiteer Adolf Messer (1878–1954). Messer’s welding, cutting and industrial gas company employed slave labor and manufactured weapons for the Third Reich. In 2019, student protests forced Frankfurt’s Goethe University to rename a campus lounge that honored Messer. See coverage in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (Google translation here) and Frankfurter Rundschau (Google translation here).

Taufkirchen (bei München) and three other locales – A street named for Willy Messerschmitt (1898–1978), eponymous airplane engineer whose firm used inmates from the Gusen I and Mauthausen concentration camps. The prisoners toiled under heinous conditions, with the death toll rising into the tens of thousands. Above left, Messerschmitt (right) with Hermann Göring at a Messerschmitt factory, 1941. Above right, prisoners at a Messerschmitt plant.

After the war, Messerschmitt served two years in prison at which point he was released and promptly continued to run his firm. He has more streets in Bergheim, Essingen (Baden-Württemberg) and Laupheim.

Teningen – A street and a plaque on the Protestant church of Köndringen (Evangelische Kirche Köndringen) honoring aluminum magnate Emil Tscheulin (1884–1951). Tscheulin was an early adopter who played a crucial role in establishing the Nazi foothold in Teningen. Afterward, he was appointed Wehrwirtschaftsführer, appropriated stolen Jewish businesses and heavily utilized slave labor, including from concentration camps.

In 2011, Teningen’s citizens initiated a review of Tscheulin’s bloody past; both the street and the church now have explanatory tablets about the profiteer.

Kassel – The official city website touts August Bode (1875–1960) as an “ingenious designer…the Nestor of wagon construction,” likening him to the ancient Greek sage. (Google translation here). What the profile doesn’t mention is Bode’s railroad wagon firm Wegmann used slave labor from thousands of concentration camp inmates and prisoners of war. It also omits the fact Bose was a Nazi Party member, Wehrwirtschaftsführer and financial supporter of the SS. Kassel has refused to rename Bode Street. Above right, Buchenwald prisoners building the Weimar-Buchenwald rail line, 1943.

Völklingen – In 1935, steel tycoon Hermann Röchling (1872–1955) urgently petitioned Adolf Hitler with a problem: Röchling was worried the Nazis weren’t being antisemitic enough. The fervent Third Reich supporter lived in the Saar industrial region on the border of France and Germany. He was concerned that insufficient repression of Jews risked turning the Saar into “a Jewish nature reserve.”

During WWII, Röchling was appointed Wehrwirtschaftsführer and proceeded to use slave labor in his steel works: 261 slaves were killed, including 60 children. After the war he was convicted of crimes against humanity, which hasn’t stopped his home region from giving him a memorial. Below left, Rochling giving the Nazi salute; below right, Rochling meets with Hitler.

***

Coburg and two other towns – Coburg has a rich history with the Third Reich: in 1931, it became the first German town to elect a Nazi mayor, its coat-of-arms once featured a swastika and the Nazi Party’s first national honor was the Coburg Badge. Coburg also has a bust and street named after Wehrwirtschaftsführer and Nazi Party member Max Brose (1884–1968), who made a fortune during the Third Reich and used slave labor.

Brose’s firm, today called Brose Fahrzeugteile, adorns its headquarters with a bust of its founder. In 2015, despite protests from the Central Council of Jews in Germany (the country’s largest Jewish organization) Coburg honored Brose with a street. The naming was championed by Brose’s grandson, the billionaire CEO of Brose Fahrzeugteile. Brose also has streets in Hallstadt and Weil im Schönbuch.

See coverage in the Financial Times, Focus Online (Google translation here), inFranken.de (Google translation here) and Süddeutsche Zeitung (Google translation here and here).

Kleinostheim – The corporate history section of the website for precious metals and technology company Heraeus admits it used forced laborers from seven countries and that Reinhard Heraeus (1903–1985) was one of the two cousins running the company during that time. Today, the corporation’s Kleinostheim subsidiary is located on Reinhard Heraeus Ring.

There are no available photos of Heraeus. Above left, Ravensbrück prisoners weaving straw; above right, inmates doing construction at a quarry near Buchenwald.

Munich – A street for Friedrich Hilble (1881–1937), head of the Munich welfare office who eagerly advocated for “work-shy” individuals – the unemployed and those on welfare – to be sent to the Dachau concentration camp. Dachau was the first regular camp established by the Third Reich; the arrest and imprisonment of “asocials” was a key step toward preparing Germany for the notion of eliminating “useless” individuals. Munich has not renamed Hilble’s street despite the city archives recommending it. See coverage in Süddeutsche Zeitung (Google translation here) and Bild (Google translation here).

Fürstenfeldbruck and 45 other locales – A street for Wernher von Braun (1912–1977), the scientist responsible for giving Germany the infamous V-2 rocket used to shell civilian areas. Von Braun, a Nazi Party member and decorated SS officer, built his rockets using slave labor from the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp complex where, for the first six months of its existence, inmates were forced to live and work underground.

There are many accounts of the conditions in these hellish worksites where prisoners were routinely murdered by starvation and exhaustion. Von Braun himself visited the Dora camp system over a dozen times; he was well aware of these conditions. After the war, von Braun rose to fame working for NASA. According to a von Braun expert, he never came close to taking responsibility over his use of slave labor. Above left, von Braun with Third Reich military brass, 1941.

Germany had renamed its last von Braun school in 2015, but he still has dozens of streets including in Amberg, Ampfing, Aschau am Inn, Baunatal, Bonn, Bruckmühl, Bürstadt, Denklingen, Ditzingen, Dreieich, Elze, Eppelheim, Eschenbach in der Oberpfalz, Fröndenberg, Gersthofen, Grafschaft, Heusenstamm, Höchst im Odenwald, Jockgrim, Königsbach-Stein, Laupheim, Leimen (Baden-Württemberg), Limeshain, Mainz, Miden, Neu-Isenburg, Neuss, Oberaudorf, Oberkochen, Oberkotzau, Olfen, Osterholz-Scharmbeck, Pirmasens, Putzbrunn, Roding, Thannhausen, Viernheim, Wagenfeld, Waldkreiburg, Wallenhorst, Walsrode, Wildeshausen, Zirndorf and Zweibrücken. There’s also a von Braun bas-relief in the recently decommissioned Berlin-Tegel airport; the relief’s fate is unclear. See Süddeutsche Zeitung on the stirring quest of Holocaust survivor David Salz to get von Braun’s name stripped from a German school (Google translation here). See the U.S. section for more von Braun honors. Note: The streets in Baunatal, Fröndenberg, Oberaudorf, Oberkochen, Oberkotzau and Waldkreiburg were added to this entry in January 2023.

Left: Klaus Riedel. Right: Riedel bust, Bernstadt auf dem Eigen (Wikimedia Commons). Image by Forward collage

Bernstadt auf dem Eigen – In 2008, relations between the U.K. and Germany hit a tense point when Britain learned about the naming of a German middle school after Klaus Riedel (1907–1944), designer of the V-2 rocket used by the Nazis to kill thousands of Brits. Despite the uproar, Bernstadt refused to rename the school, which has a bust of the designer; the city also has a bust of Riedel (see photo). According to Riedel’s biographer, the scientist “knew exactly what the rocket would be used for.” Note: The school’s bust to Riedel was added to this entry in October 2022.

Munich – In 2010, Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko orchestrated the installation of a plaque to Yaroslav Stetsko (1912–1986) and his wife who had lived in Munich after WWII. Stetsko was a leader in the Stepan Bandera faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-B) paramilitary which had collaborated with the Nazis and participated in the Holocaust.

Stetsko’s antisemitism reached genocidal levels: he had written “I insist on the extermination of the Jews and the need to adapt German methods of exterminating Jews in Ukraine.” Five days prior to the 1941 Nazi invasion of Ukraine, Stetsko assured Bandera: “We will organize a Ukrainian militia that will help us to remove the Jews.” The OUN-B followed through by inciting and participating in mass pogroms right as Germany invaded. Stetsko also led the OUN-B’s self-proclaimed government which had formally pledged allegiance to Hitler. See the Ukraine and U.K. sections for more Stetsko glorification.

Weissach – Added October 2022 — A kindergarten honoring Ferdinand Anton Ernst Porsche, commonly known as Ferry Porsche (1909–1998). Like his father Ferdinand Porsche (see earlier entry), Ferry Porsche was a member of the Nazi Party and an SS officer involved with slave labor in the Porsche factory in Stuttgart.

See coverage in Haaretz and the book “Nazi Billionaires” by David de Jong (his essay on Porsche in Forbes here). See the Austria and U.S. sections for more Ferry Porsche honors.

Plattling – added March 2024 – A memorial plaque to soldiers of the Russian Liberation Army (ROA) at the town’s war cemetery. The ROA, a Russian collaborationist formation in the Third Reich, was led by Andrey Vlasov, a Soviet general who had defected to Germany. According to historian Christopher Simpson, “Vlasov’s organization consisted in large part of reassigned veterans from some of the most depraved SS and “security” units of the Nazis’ entire killing machine.”

Above left, Vlasov (second from left) and fellow collaborator Fyodor Truhin (far left), in Dabendorf, 1944. Note the ROA patch on Truhin’s arm. Above right, Vlasov speaking to ROA troops, 1944. See the Czech Republic, Russia and U.S. sections for more monuments to Russian collaborators.

Editor’s note: In addition to the above, Germany has many streets and monuments to people whose World War II activities did not meet the criteria for inclusion in this project, but are nonetheless problematic. They include:

- bacteriologist Paul Uhlenhuth, who denounced Jewish colleagues to the Nazis and applied for permission to conduct experiments on concentration camp inmates (historians aren’t sure whether the experiments were carried out, otherwise Uhlenhuth would’ve been included in the project);

- transportation magnate Alfred Kühne, who forced out his Jewish business partner (who was later murdered in Auschwitz), joined the Nazi Party and transported stolen possessions of murdered Jews for the Nazis;

- antisemitic writers Heinrich Sohnrey (whose work influenced the Nazi movement), Agnes Miegel (who extolled Hitler in poems), Gustav Frenssen (who churned out rabidly antisemitic tracts), Waldemar Bonsels and August Lämmle;

- composer Hans Pfitzner, a Holocaust denier;

- Nobel laureate Konrad Lorenz, a Nazi Party member who worked in the Office of Racial Policy promoting eugenics;

- Nazi functionary Fritz Kiehn;

- Evangelical Lutheran bishop August Marahrens, who sidled up to the Nazis.

See coverage of the above examples in Forbes, Der Spiegel, the New York Times, JTA, Handelsblatt, taz (Google translation here), Die Welt (Google translation here), DW and Zeit.

A particularly fascinating and ongoing case is about the legacy of pathologist Robert Rössle, who is honored with a bust, street and medical research institute/hospital in Berlin. See discussion in Time.news and coverage of the quest of Dr. Ute Linz to remove Rössle’s honors in taz (Google translation here) and Berliner Zeitung (Google translation here).

There’s also the strange case of numerous German towns with church bells dedicated to Hitler, which gives a fascinating glimpse into battles over the country’s Nazi legacy.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO