Nazi collaborator monuments in Austria

Multiple honors for Ferdinand Porsche and his son, Ferry

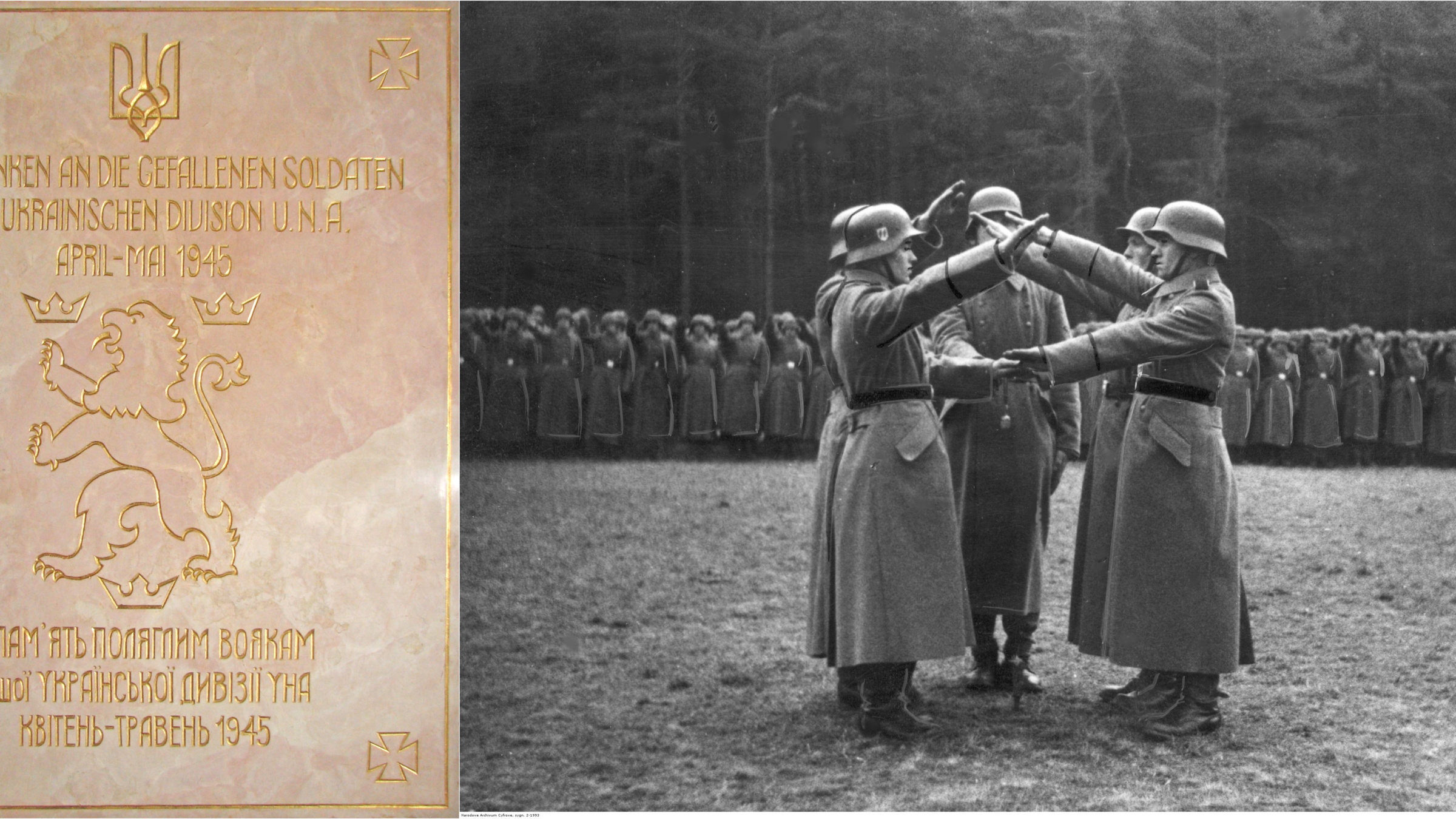

Left: SS Galichina plaque inside the Alte Kirche, Feldbach (Wikimedia Commons). Right: SS Galichina soldiers entering the division taking oaths, April 1943 (National Digital Archives Poland). Image by Forward collage

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email editorial@forward.com, subject line: Nazi monument project.

Note: in addition to the names listed here, Austria has numerous streets and monuments to individuals who were antisemites or outright Nazis but did not fully meet the criteria for inclusion for this project. Examples include chemist Richard Kuhn, who denounced Jewish colleagues; poets and prominent Nazi Party members Maria Grengg and Karl Pschorn; political leader Karl Renner, who advocated for the Nazi takeover of Austria; the Nobel laureate Konrad Lorenz, a Nazi Party member who worked in the Office of Racial Policy promoting eugenics; and others. See coverage in the Forward, The Local.at, Der Spiegel, the New York Times and JTA.

Gmünd (Carinthia) and 16 other locales — A park and bust of Ferdinand Porsche (1875–1951), an automotive engineer who designed the eponymous car line and the Volkswagen Beetle. He was also a decorated member of the Nazi Party and the SS who built weapons like the Tiger tank for the Nazis. Most disturbingly, his plants used slave labor from Eastern European conscripts and concentration camp inmates; the Volkswagen plant is infamous for murdering up to 400 infants — the children of its slave workers.

Vienna’s Ferdinand Porsche Street is a good example of the inherent limits of contextualization: the idea that streets and monuments to despicable figures should be dealt with not by renaming and removal but via explanatory plaques highlighting the honoree’s dark side (contextualization is being considered for Confederate statues in America).

In 2013, a report commissioned by the Vienna government listed Porsche’s street as a top priority for “intense discussions.” Instead of renaming, the city went with contextualization. Porsche’s street now has a plaque explaining that “The problems in [Porsche’s] biography are his membership in the NSDAP [Nazi Party] and SS, the employment of forced laborers and his work in the Nazi armaments industry.” (below left).

Critics in the newspaper Kurier have pointed out that the fact that those “problems” weren’t considered problematic enough to rename the street only reinforces the whitewashing: the message is that Vienna is fully aware of Porsche’s horrific acts, but does not deem them to be grounds for disqualification.

See the street name report (in German), Vienna press release about installation of explanatory plaques (Google translation here) and coverage of protest action of the Austrian Union of Jewish Students which drew attention to Vienna street names on the anniversary of Kristallnacht.

Porsche also has a monument at the Vienna University of Technology (below right); a bust in the St. Peter an der Speer museum, the Ferdinand Porsche FernFH university (partially owned by the province of Lower Austria) and a street in Wiener Neustadt; a museum at Mattsee; and streets in Amstetten, Enns, Felixdorf, Graz, Hallein, Knittelfeld, Krems an der Donau, Leibnitz, Linz, Salzburg, Sierning, Steyr, Tullnerbach-Lawies and Wals-Siezenheim. (Note: this paragraph was updated in October 2022.)

Update (August 2023): Linz’ Porsche Street has been renamed Wittensteinweg after philosopher Ludwig Wittenstein. Thanks to Johannes Kaska of the Archives of the City of Linz for aid in tracking this story.

See the Czech Republic, Germany and U.S. sections for more Porsche monuments.

***

Vienna — A street named for Franz Häußler (1899–1958), teacher who founded the Jung-Urania Nazi youth organization. Häußler created Jung-Urania in 1934, after Austria shut down other Hitlerite youth groups. His goal was to ensure the fostering of Nazism in children. When the Third Reich took over Austria in 1938, Häußler became a Nazi Party member and Jung-Urania was absorbed into the Hitler Youth. See Häußler’s biography on the Vienna government street listing page (Google translation here).

Above left, Hitler Youth hanging signs on Vienna Jewish shops to mark them as Jewish-owned. Above right, Hitler Youth forcing Jews to clean the streets of Vienna, 1938. Such rituals of public humiliation often precede genocide; over 47,000 Austrian Jews were murdered in the Holocaust.

Feldbach and two other locales — A plaque to soldiers of the 14th Grenadier Division of the Waffen-SS (1st Galician) aka SS Galichina. This was a Ukrainian unit in the Waffen-SS, the military arm of the Nazi Party responsible for carrying out the Holocaust. SS Galichina became known for war crimes such as the 1944 Huta Pieniacka massacre, when its fighters burned 500–1,000 Polish villagers alive.

Southeast Austria has gravesites of SS Galichina fighters in Feldbach and nearby towns. After the war, veterans’ groups erected several memorials to this Waffen-SS unit. The memorials coyly refer to SS Galichina as the “1st Ukrainian Division of the Ukrainian National Army”. SS Galichina was renamed this at the very end of the war; the unit’s whitewashers use this on memorials because it doesn’t include the attention-grabbing “SS.”

Feldbach’s Alte Kirche Catholic Church has an SS Galichina plaque inside the church (above left) as well as a separate stone memorial outside. In 2018, the town removed the lion and crowns divisional insignia from the stone memorial. Removing the SS Galichina symbol was billed as a “compromise” to allow the memorial to remain. It’s unclear whether the lion and crowns insignia was removed from the plaque inside the church as well. It should also be noted that the “compromise” fails to address the core issue, say critics, which is that even without the insignia, the monument clearly honors and glorifies a Waffen-SS division that committed war crimes.

There are additional SS Galichina memorials in Bad Gleichenberg and the parish church at Bierbaum am Auersbach. Above right, SS Galichina oath ceremony, 1943.

See Twitter thread from Moss Robeson who found videos of SS Galichina veterans holding commemoration ceremonies at these memorials. See the Australia, Canada and Ukraine sections for more SS Galichina monuments.

#Thread of monuments & memorials in southeastern Austria honoring the Ukrainian (“Galician”) Division of the Waffen-SS, which apparently played a significant role in staving off the Red Army there in the last few weeks of WW2, effectively securing the area for British occupation. pic.twitter.com/HBEH8VC6DA

— Bandera Lobby Blog (@mossrobeson__) July 4, 2020

Zell am See – Added October 2022. The Ferry Porsche Congress Center convention and performance venue, above left, and a street honoring Ferdinand Anton Ernst Porsche, commonly known as Ferry Porsche (1909–1998). Like his father, Ferdinand Porsche, Ferry Porsche was a member of the Nazi Party and an SS officer involved with slave labor in the Porsche factory in Stuttgart.

See coverage in Haaretz and the book “Nazi Billionaires” or Forbes essay by David de Jong. See the Germany and U.S. sections for more Ferry Porsche honors.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO