An Ashkenazi delicacy made of fish sperm

It was popular not just with Jews, but with Poles who ate it for the meatless Christmas Eve meal

Illustration by Mira Fox

It was a simple meal. Herring, potatoes, bread and kratsborsht — a sweet and sour sauce made from the sperm of a mature male herring.

My father, Mayer Kirshenblatt, recalls his mother making this meal in Opatów (Apt, in Yiddish), Poland, when he was a child. My father associated herring, which was abundant and relatively cheap, with poverty. But herring dressed with milt sauce (milt refers to the fish semen) has a long and distinguished history in East and Central Europe. Even the name of the dish reflects its venerable status.

Herring in the Old Polish Style (Śledzie po staropolsku) is one of several fish dishes Poles eat for Wigilia, Poland’s meatless Christmas Eve meal. In the most popular Jewish cookbook of the 19th century — Rebekka Wolf’s Kochbuch für Israelitische Frauen (Cookbook for Jewish Women) — milt sauce appears in the recipe for Häringsalat (herring salad). Wolf’s book was so popular that between the years 1851 and 1933 it went through 14 editions.

The Jewish authors of two other popular cookbooks included recipes for this sauce as well. Aunt Babette’s Cook Book (1889) and The Settlement Cook Book (1903) explain how to prepare pickled or marinated herring from scratch, including the instructions for the milt sauce. One distinct advantage of milt sauce for Jewish cooks was that it provided creaminess without the cream, making it pareve, so it could be served at meat meals.

In Polish cookbooks published in the early 19th and 20th centuries, the milt sauce in recipes for marinated herring (Śledzie marynowane) and the ingredients in herring sauce (Sos ze śledzi) are almost identical to kratsborsht but they add the sauce to the herring, rather than serve it as a dip the way my grandmother did.

Calling milt sauce kratsborsht seems to be unique to Yiddish speakers. The word krats means “scratch” or “scrape.” To make a kratsborsht you have to open the milt sac and scrape the semen from the membrane. Gad Zaklikowski, in the memorial book for the town of Sokolov-Podliask, recalls a cook who served “hering-milkh” (herring milt) sauce together with the herring, and then said: “This is a kratsborsht.” Zaklikowski himself must have found the name odd because he added, “That is what she called it,” as if to say “I’m not making this up.” He also praised her presentation of this dish, saying it was like “a wealthy man’s meal.”

You also find the delicacy mentioned in Yiddish literature. Sholem Aleichem’s 1901 sketch about a restaurant in his fictional shtetl, Krasrilevke, includes a scene where the proprietress asks the guest if he would prefer his herring with roe (fish eggs) or milt.

Kratsborsht even made it to American shores. In 1904, a young man, Joel Russ, arrived in New York from the town of Strizev (Strzyżów in Polish) and began peddling herring from a barrel on the Lower East Side — a common trade in those days. Not long after this, he established the renowned appetizing business Russ & Daughters.

Throughout the years, many Jewish homemakers have bought herring from Russ & Daughters. Herring with kratsborsht remained a classic dish on the American Jewish table well into the 1970s, when Mark Federman, the third generation to run Russ & Daughters, took over the business.

During the 1990s, as Federman recalled in an interview, the FDA ruled that cured uneviscerated fish and the wooden barrels in which they were delivered posed a health hazard. After that, gutted herring, without roe or milt, began arriving in plastic barrels. Before the FDA ruling, Russ & Daughters employees would give the milt to customers who asked for it or they’d discard it. As Federman noted, “The milt was the original cream sauce, without the cream. I tasted milt but found it off-putting.”

Demand for herring declined as old-timers avoided salt, moved to Florida or passed away, while for the younger generation, Federman said, “Herring is an acquired taste, because they don’t like it to start with. They consider it déclassé, disgusting.”

That might just change, thanks to Josh Russ Tupper and Niki Russ Federman, the fourth generation to run Russ & Daughters, who recently added “Schmaltz and a Shot” to the menu of their trendy café on Orchard Street. The appetizer consists of schmaltz herring, a boiled potato, raw onion and a shot of vodka. For the younger demographic, Federman said, “acquiring a taste for herring is a rite of passage.”

As for kratsborsht, it remains a lost culinary tradition of the Yiddish table awaiting its rediscovery by a new generation.

*

Below you’ll find what my father, Mayer Kirshenblatt, recalled about kratsborsht in his hometown of Apt (Opatów, in Polish):

Mother sent me to my grandmother’s store to buy a herring. They did not wrap herring in paper as paper was in short supply, and even newspaper was precious. The shopkeeper would wrap a little piece of newspaper around the middle of the herring, just big enough for my hand to hold it. Brine would drip from the head and tail of the herring. On the way home, I would lick the drops of brine.

A herring was an important part of the diet. A woman could make a whole banquet from a herring. When purchasing a herring, you always asked for a male. After washing the herring and opening it up, mother would remove the milt or milekh, a long sack of semen. She would open the milt and scrape the semen away from the membrane, which she threw away. To the semen, the zumekhs, she added minced onion and a little vinegar and sugar to taste to make a sauce, a zuze. This was called a kratsborsht or scratch borsht because the semen had been scraped from the membrane. Everyone got a little piece of herring, a small piece of bread to dip in the kratsborsht, and maybe also a boiled potato. That was supper.

A few boiled potatoes, bread, and a piece of the herring made an excellent meal for a poor family. My mother had to be a gourmet cook to make a herring into a meal for the whole family. One herring would feed a family of four or five. Many people did not even have that and went to bed hungry.

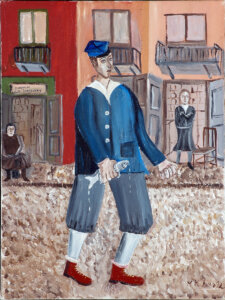

(This and many more of Meyer Kirshenblatt’s memories of Apt can be found in the book, They Called Me Mayer July: Painted Memories of a Jewish Childhood in Poland Before the Holocaust, which also includes his paintings to illustrate the stories. He began painting these memories in 1989 when he was 73 years old. An exhibition featuring his artwork will open in May at POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw.)

Recipe for Kratsborsht

1 milt

White vinegar and sugar to taste

Water

1 small minced sweet onion

Remove the milt from a mature male herring.

Gently cut open the milt and scrape out the semen. Mash it well or strain through a sieve. Discard the membrane.

Add vinegar and sugar to taste, mixing well to make a creamy sauce.

Add a little water to adjust the taste and consistency.

Add minced onion.

Serve with pieces of rye bread for dipping, alongside slices of herring and boiled potatoes.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO