The British Chief Rabbi that never was

Rabbi Louis Jacobs was ostracized by the British Orthodox rabbinate but his view of Jewish theology resonated for me

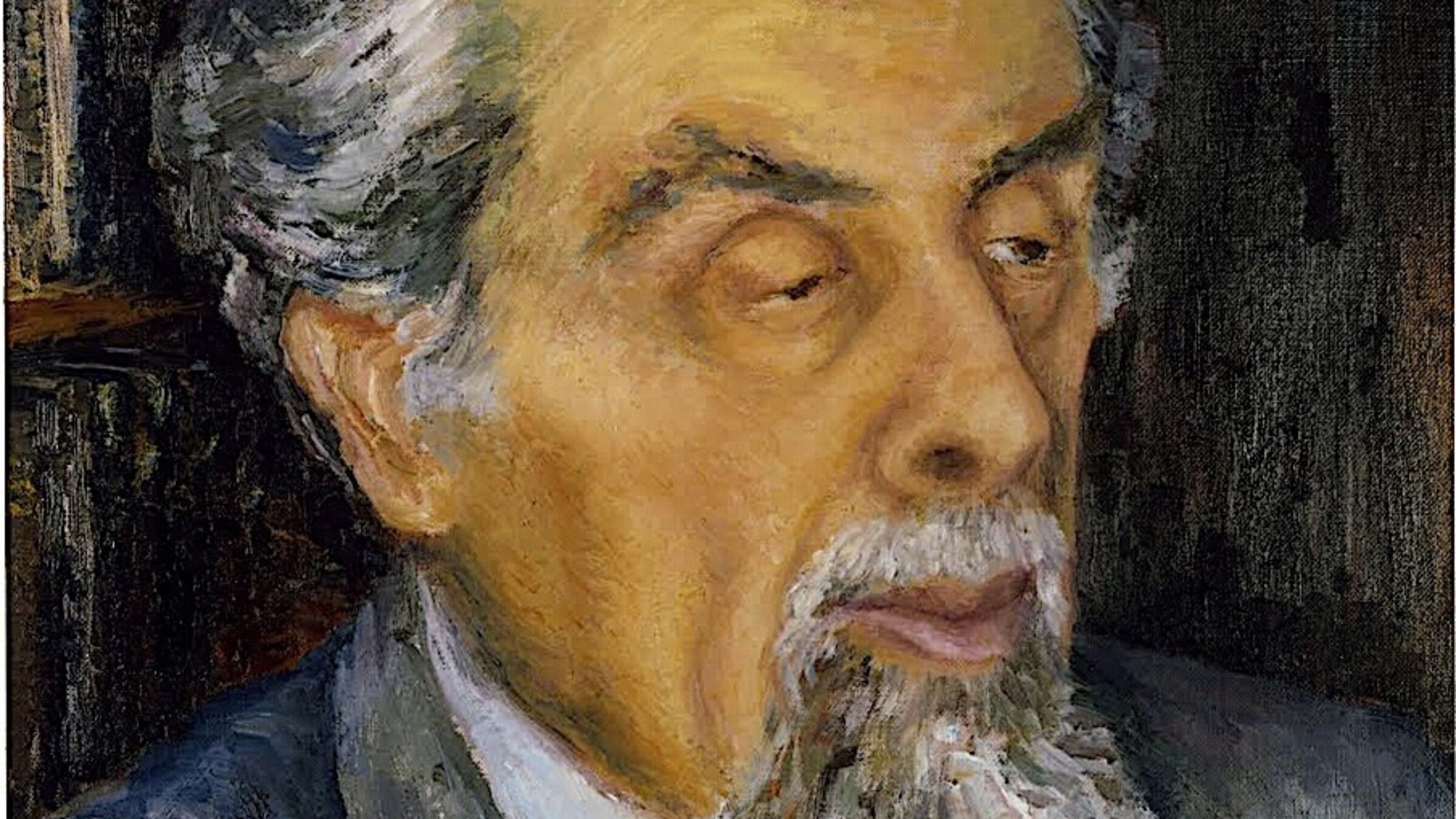

Courtesy of Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies

Rabbi Louis Jacobs (1920–2006) was the greatest British Jew who ever lived, according to a 2005 survey by The Jewish Chronicle. This was a surprise to me, since I never even heard of him until I was 22 years old.

While Rabbi Jacobs had stellar Orthodox credentials, his unique understanding of Jewish theology ruffled many feathers within the British Orthodox establishment. For a time in the 1960s, Rabbi Jacobs was in line to become the chief rabbi of the British Commonwealth. But once he published his seminal book We Have Reason to Believe he was sidelined and ostracized from the United Synagogue. He never became the chief rabbi.

Why? The book challenged the traditional belief in the origins of the Torah.

My first interaction with Rabbi Jacobs came about in a most unusual way. As a student in the Chabad Semikhah (ordination) program in Melbourne, Australia, in 2002, most of my waking hours were spent on the minutiae of Jewish law. I was studying the Shulkhan Arukh, a 16th-century code of Jewish law by Rabbi Joseph Caro. We studied the rudiments of the kosher slaughtering process and the complex laws surrounding the kosher kitchen.

One afternoon, I noticed a fellow rabbinical student reading a book called The Search for God at Harvard, by journalist Ari Goldman. Since my own father discovered God during his time at Harvard in the early 1970s, I was curious to read the book. So I borrowed it.

‘The Torah did not descend from heaven’

About halfway through the book, Goldman introduces Rabbi Jacobs, who at the time in the mid-1980s was a visiting scholar at the Harvard Divinity School. Rabbi Jacobs believed that the Bible, the Torah, did not descend from heaven the way most Orthodox Jews believe. Based on the formulation of Maimonides, or the Rambam, in his seminal code of law, the Mishna Torah, Orthodox Jews believed that the Five Books of Moses were literally dictated by God to Moses, without any input or originality on the part of Moses himself.

Jacobs rejected this simplistic formulation on account of the many discoveries made in ancient Near East studies, geography, anthropology, linguistics, and general historical knowledge. For him, while the Torah was divinely inspired, it was also a product of its time and place. In the 30 books he published over the years, Jacobs labored to explain that the Torah was indeed from God, but not in the way it was conventionally understood.

For me, reading about Jacobs’ unique understanding of Jewish theology was like manna from heaven. For years, I struggled to accept that God dictated each and every word of the Torah to Moses. This became apparent to me when I noticed the differences between the two versions of the Ten Commandments. The first version appears in the book of Exodus and the second — in the book of Deutoronomy.

How Israelites’ rituals were influenced by Egyptian practices

For example, the last of the ten commandments warns against coveting your neighbor’s possessions, such as his house, his wife and his servants. However, while the first version in Exodus lists “house” before “wife,” in Deuteronomy the order is reversed, with “wife” listed before “house.” If God literally dictated the Torah to Moses, why would he reverse the order in the second version?

To my surprise, even the Haredi Artscroll publication on the Torah (the Stone Edition) acknowledges that it was Moses who reversed the order in Deuteronomy. Commenting on the second version of the Ten Commandments, Artscroll writes: “In Exodus, property is mentioned first, but here Moses mentioned sensual desire first because average human beings have stronger lusts for sensual gratification than for additional property.”

If it was Moses who reversed the order, then clearly the second version of the Ten Commandments was not dictated by God.

In another example, the ancient Israelites were enslaved in Egypt for some four hundred years. Our forefather Jacob and his son Joseph were embalmed with the ancient Egyptian funerary rites. The Bible recounts (Genesis, chapter 50) how the patriarch Jacob was mourned for 70 days. However, unlike today when the shiva (the seven-day mourning period) is practiced following the burial, the 70 days of mourning for Jacob took place prior to his burial. Clearly, they did this on account of the ancient Egyptian practice of mourning prior to the burial. This difference highlighted for me how the Bible was a product of its time and place. Continuing to believe in the literal dictation by God to Moses became untenable.

The perils of sharing Jacobs’ theology with family

Rabbi Jacobs’ theology rang true to me and I tracked down many of his books at the small Jewish public library in Melbourne, known then as Makor. First, I read his most controversial book, We Have Reason to Believe. Then I turned to his books Beyond Reasonable Doubt, Helping With Inquiries: An Autobiography, and Principles of the Jewish Faith. I especially enjoyed his book Religion and the Individual: A Jewish Perspective, published by Cambridge. After I returned to Brooklyn, I began sharing Rabbi Jacobs’ books with friends and family members. Since no members of my family had ever heard of Rabbi Jacobs, it was all a curiosity to them, and they didn’t take his ideas too seriously.

With time, one of my sisters married a Hasid from London, who knew very well what Rabbi Jacobs stood for. As I showed my brother-in-law one of the Jacobs books in my home library, he frowned and proclaimed: “You know, Rabbi Jacobs is an apikores, a heretic!”

I smiled politely but didn’t respond. It was clear that it wasn’t just Rabbi Jacobs he was accusing of heresy.

Jacobs saves the day for Chabad

Ironically, it was Rabbi Jacobs’ expert testimony in 1985 that helped secure a victory for the Chabad movement in its legal battle over the Chabad library, despite the fact that Chabad leaders no doubt saw him as a heretic too. At the time, the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s nephew, Barry Gurary, removed priceless books from the main Chabad library, claiming that they were his as an inheritance from his grandfather, the previous Chabad rebbe Yosef Yitzchok Schnersohn. In order to compel Gurary to return the books, Chabad sued him in civil court.

Chabad paid Rabbi Jacobs $6,200 for his appearance in court during the bitter civil litigation that ensued. Even though Chabad considers him a heretic, it was Jacobs’ testimony that ultimately brought about the victory they so desperately needed.

To this day, I continue buying and reading books by and about Rabbi Jacobs. Throughout my first job as a rabbinic intern in Somerset, New Jersey I used Rabbi Jacobs’ book of sermons, Jewish Preaching: Homilies and Sermons, as the basis for my own weekly Sabbath talks. I frequent the website, Friends of Louis Jacobs, run by Jacobs son Ivor. I continue to follow the scholarship regarding what has regrettably become known as the “Jacobs Affair.” The recently issued biography on Jacobs by Harry Freedman, Reason to Believe: The Controversial Life of Rabbi Louis Jacobs, was wonderful. When asked: “So what kind of Jew are you?”, my answer remains the same: “I’m a Jew for Jacobs.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO