More than shtetl and pogrom: Inside the movement to translate Yiddish

A group of Yiddish translators wants the world to know how modern, feminist and relatable Yiddish literature actually is.

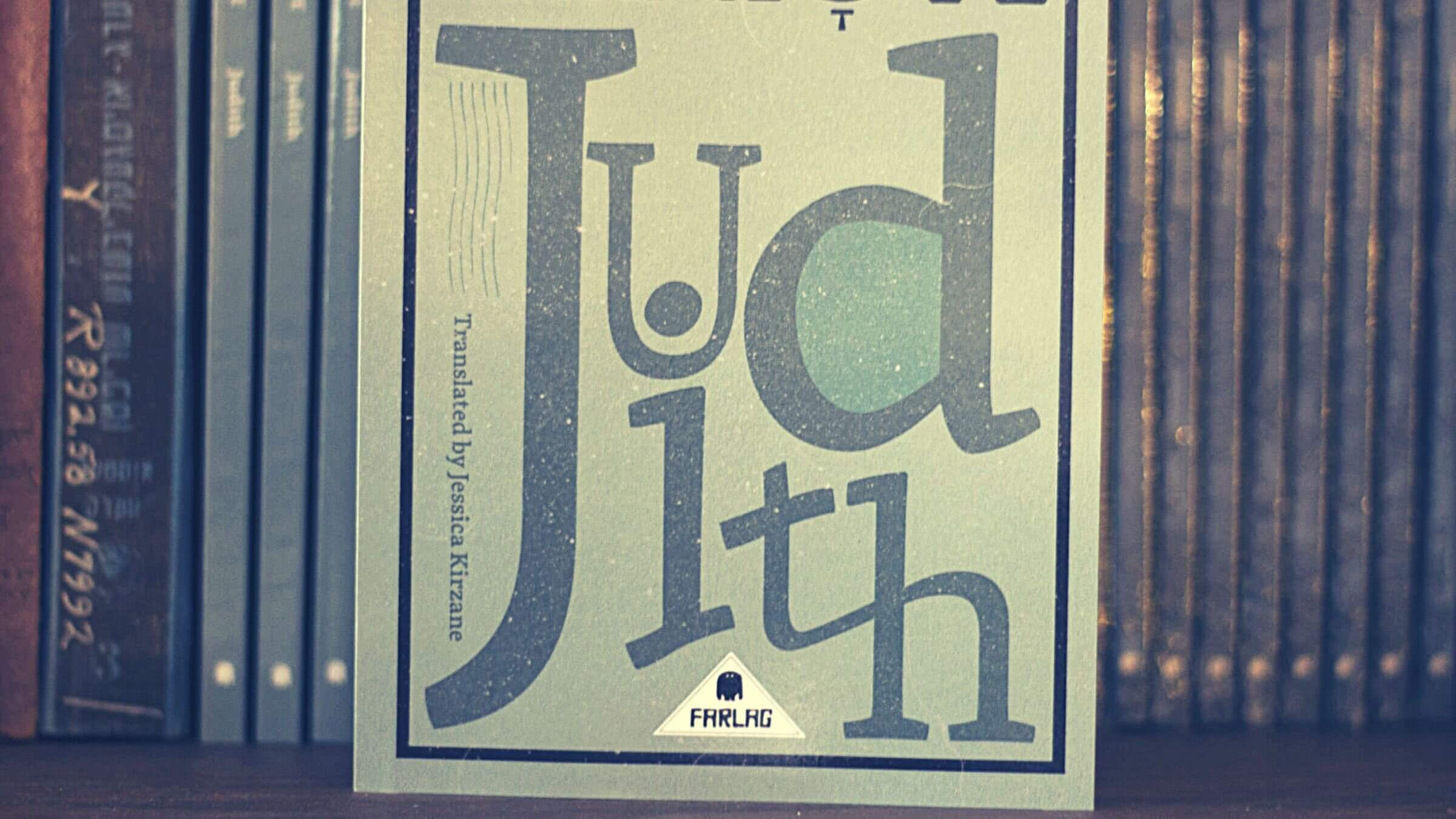

“Judith” by Miriam Karpilove, translated by Jessica Kirzane, published by Farlag Press. Courtesy of Farlag Press

“Yiddish has been made to represent the failure of Jewish life in Europe,” remarked Mindl Cohen, academic director of the Yiddish Book Center. Connecting Yiddish with shtetls, pogroms and the Holocaust created a narrative of an old-fashioned way of life that disappeared in the wake of modernity and antisemitic violence. The message was that “this culture didn’t survive, maybe because it wasn’t fit to,” Cohen said.

But the narrative might change if Yiddish literature were better known. Yiddish didn’t lose the battle with modernity; on the contrary, modern Yiddish literature thrived in the 20th century and never died. “Read a crazy sexy poem from a woman writer in the nineteen-teens,” Cohen suggests. Or a novel about a man who indulges in continental philosophy in interwar Berlin. Or a novel by a woman about her skepticism that “free love” in turn-of-the-century New York was good for women.

If only people knew. The problem is, relatively few secular people can read modernist Yiddish writing. (Hasidic Jews speak Yiddish, but are unlikely to read secular Yiddish literature.) And because of the dominant narratives around Yiddish, there’s no demand for it in translation. Instead, people turn to Yiddish literature to experience a lost world of Jewish tradition that serves as an escape from modernity as well as a post facto justification for its demise.

“People have preconceived ideas of what Yiddish is; if you’re going to read something in translation from what Yiddish is, you want it to fit a sentimentalized view of the Jewish world, and fit your preconceived view of that world including Holocaust memoirs and religiosity,” said Jessica Kirzane, assistant instructional professor of Yiddish at the University of Chicago. “There is an expectations gap; Yiddish literature is not just about Jewishness. So much of Yiddish literature was about modernization, and was rebelling against the Jewishness that people turn to Yiddish for.”

The expectations gap is related to the limitations of the Yiddish literary canon. Many of those considered to be “classical” writers, like Mendele Mocher Sforim, Sholem Aleichem and Y. L. Peretz, depicted the old shtetl as backwards places worth poking fun at and longing for in equal measure. Female writers have been shut out of the canon, with the exception of their poetry. The canon is what influenced public knowledge of Yiddish culture, because these were the works that were translated and popularized, furthering the narratives of backwardness and the inability to modernize.

Yet in the Soviet Union, modernist Yiddish writers dominated the literary scene (though many were later executed by Stalin). Soviet-Yiddish writers were comfortable with urban, sophisticated Europe and complex narratives, yet their work is not widely known or associated with Yiddish. One such writer was Moyshe Kulbak, whose “Childe Harold of Dysna” depicted an Eastern Europe protagonist going to cosmopolitan, interwar Berlin, indulging in existentialist philosophy and becoming a socialist.

The United States had its own modernist writers, many of them women. In early 20th century New York, Miriam Karpilove wrote “Diary of a Lonely Girl.” The book takes readers through the dating life of a woman unsatisfied with the modern, leftist concept of “free love.” In the latter half of the 20th century, Blume Lempel wrote short stories, including “Oedipus in Brooklyn,” a complicated and disturbing tale about a woman in an incestuous relationship with her blind son, pretending that he is her dead husband.

These stories challenge public understandings of Yiddish literature and culture, but have been locked away because they’re only available in Yiddish.

But Sebastian Schulman, executive director of KlezKanada, says the canon and therefore narratives of Yiddish culture can change. “The study of Yiddish literature is so small, comparatively, that the canon is whatever it is we decide it will be,” Schulman said. After all, only a scant 2% of Yiddish literature is estimated to have been translated.

What does it take to change these hard-wired perceptions among the general public and especially the Jewish public? It takes creating an entire infrastructure, including translator training, specialty publishing houses, social media and marketing. Ten years ago, the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, became the epicenter of this effort.

That was when Schulman started the Yiddish Translation Fellowship, devoted to training the next generation of translators under the auspices of the Yiddish Book Center. (The fellowship has been run by Mindl Cohen since 2018, herself a fellow in 2015. Kirzane was also a fellow.) Schulman staffed it with literary translators possessing backgrounds in a variety of languages to teach students how to make artful, and not just literal, translations.

Ten years and 80 fellows later, a robust network of translators trained in the art of literary translation was ready to share the manuscripts they are required to complete as part of the fellowship. But a roadblock emerged: Publishing was nearly impossible.

Large publishers typically reject most translated works, even those from more widely spoken languages. In fact, it’s estimated that only around 3% of books published in English are translations, an absurdly small number compared to other languages. (Walk into a bookstore in Israel, for example, and see for yourself how many books published in Hebrew originated in other languages.)

Because mainstream English-language publishers rarely accept translations, with the exception of a handful of classics and surefire hits, some small independent publishers emerged in the 1980s to focus almost exclusively on translated books.

Archipelago Books, for example, writes on its website that it’s “striving to find visionary international writers whom American readers might not otherwise encounter.” But therein lies the problem for Yiddish books: Yiddish writers are mostly not contemporary. It is hard to persuade even these presses that a novel from a century ago might contribute to the national literary conversation.

A handful of academic presses do publish Yiddish translations. Notably, the Yiddish Book Center partnered with Yale University Press to issue 10 translations in the New Yiddish Library series, and Syracuse University Press had its own Yiddish translation series. But while these publishers were amenable to releasing English translations of Yiddish books, they really didn’t change the general conversation. Their prices were so high and copies of books so few, they had a hard time reaching the non-academic public.

Over time, it became clear that there was a need for publishing houses dedicated specifically to Yiddish translation, that could sell copies widely and cheaply. Schulman, who has translated from Yiddish and Esperanto, observes that presses that publish translations from less-known languages can serve as advocates for them.

In the last few years, frustrated fellowship-trained translators have launched their own presses in order to publish and disseminate Yiddish works: Naydus Press in Ohio, Farlag Press in France, and the Yiddish Book Center’s in-house White Goat Press.

Jordan Finkin started Naydus Press (Naydus rhymes with Midas) in 2017 as a side project to his day job as a rare book and manuscript librarian at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. He named the press after the early 20th century Yiddish poet Leyb Naydus, who infused his writing with classical Greek mythology, Western European culture and Middle Eastern motifs. “I think he’s fantastic as a true European aestheticist, art for art’s sake.” Finkin said. Naydus represents a challenge to the notion that Yiddish literature is parochial.

So far, Naydus Press has published two books, including the cosmopolitan “Childe Harold of Dysna,” translated by Robert Adler Peckerar. Finkin draws upon his translation skills and his role as Hebrew Union College Press’s co-director to get works out with a limited budget. While it costs only $5,000 to publish a book, he says “the single greatest problem is funding, because I have a full-time job; shnorring for donations is a full-time job.”

Farlag Press, which was launched in 2018, has published four books, two of them novels. One was Kirzane’s translation of another Karpilove novel, “Judith: A Tale of Love and Woe.” Three more books are due out this year. As for funding, founder Daniel Kennedy believes he has a winning formula: subscriptions. “Our approach for this year was to offer subscriptions for everything we publish in 2022. So far the response has been very encouraging and it has allowed us to gather the funds we need to produce the books,” he wrote in an email.

White Goat Press at the Yiddish Book Center has published a new Yiddish textbook and four translations since its founding in 2019. White Goat has a considerable advantage in funding compared to the other presses because it can rely on its parent organization.

But none of these publishing houses see themselves as the answer to the lack of a publishing pipeline. They would rather play an advocacy role. “White Goat Press could publish a few books a year, but we also support others to get them out to non-dedicated publishers to increase visibility,” said Mindl Cohen. “I’m helping translators make the case to small presses.” The Yiddish Book Center also gives non-Yiddish publishers funds to defray costs and encourage them to take on projects.

Alongside publishing houses, online literary journals are part of the quest for new readers. Having a short story appear in one of these journals raises the profile of relatively unknown Yiddish writers. “I’ve learned that it’s really important to publish in journals, because you’re introducing a new author,” Cohen said. At the end of the day, it’s an all-of-the-above approach. “We’re building a mix,” she said.

As these initiatives stepped up, other publishers that didn’t believe there was a market for English translations of Yiddish books started reconsidering. After Wayne State Press rejected Kirzane’s translation of “Diary of a Lonely Girl” (later picked up by Syracuse University Press) for being too niche, the publishing house changed its approach. They recently published a collection of Yiddish short stories: Anita Norich’s translations of Chana Blankshteyn’s “Fear and Other Stories.”

The conversation in the media is changing too. A recent article in The New York Times celebrated the revival of female writers by translators like Kirzane, Norich and others. The LA Review of Books published thoughtful reviews of three recent Yiddish translations, two of them from the new Yiddish translation presses: “Childe Harold of Dysna,” and “From the Vilna Ghetto to Nuremberg: Memoir and Testimony,” a collection of poet Abraham Sutzkever’s writings as a partisan fighter in World War II. “Yiddish has a seat at the table in places it never had before,” Schulman said.

College syllabi and social media have also contributed to the shift in perception. At the University of Chicago, Kirzane teaches courses about books that she and other fellowship graduates have translated. One of Kirzane’s pupils, Cameron Bernstein, made TikTok videos talking about and reenacting parts of Yiddish literature. Bernstein’s pioneering efforts got her a job at the Yiddish Book Center as a communications fellow handling the center’s social media while continuing to work on her personal TikTok, where she has more than 40,000 followers.

Schulman thinks these efforts are finally making a difference. Yiddish comes from a place of being somewhat “maligned,” he says, but this recent cultural mainstreaming is normalizing perceptions of the language, even in formerly hostile or indifferent Jewish circles. And the gradual recognition of modernity in Yiddish literature, pushed in part by the publication of translated works, is building up a new narrative of pride for the language and culture.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO