How a Hebraist Israeli party ended up boosting the Yiddish press

In honor of Yom Ha’atzmaut read why the ruling party Mapai published not one, but two Yiddish newspapers.

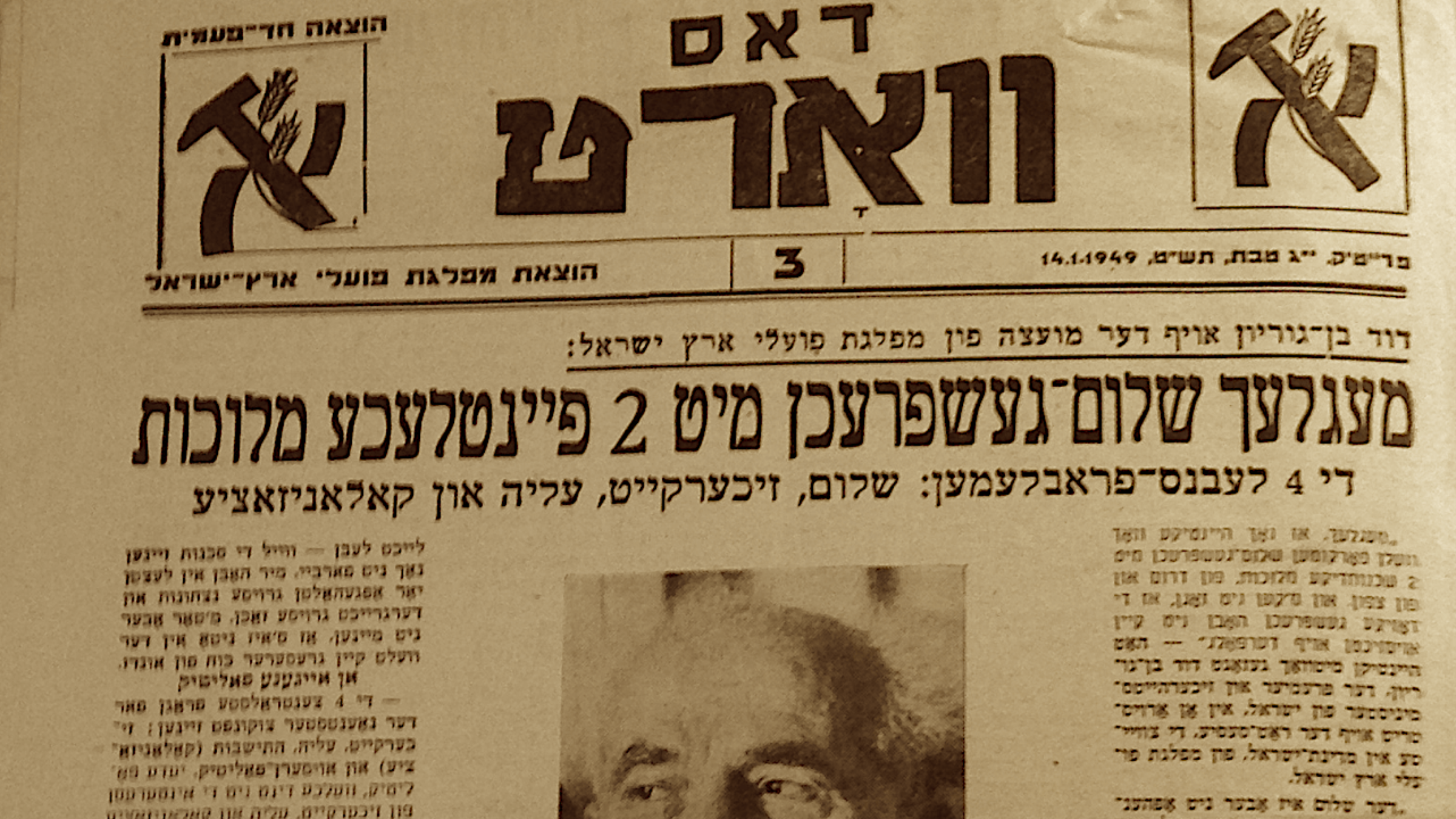

The first of two Yiddish newspapers published by the ruling democratic socialist party Mapai. Photo by Rachel Rojanski

Few Jews in Israel or abroad today know that during the 1950’s, about 100 Yiddish newspapers and periodicals were launched in the Jewish state. Some were short-lived, while others came out for a number of years, even decades. Between 1948 and 1970, 20 – 30 Yiddish newspapers and periodicals were published in Israel each year – despite the strong pressure exerted by Israeli leaders for its new citizens to learn how to speak and read Hebrew.

Only a small number of these periodicals were privately owned; the most prestigious of them being the leading daily, “Letste nayes” (Latest News), which went out regularly for five decades. Most private owners of Yiddish newspapers were new immigrants, often Holocaust survivors, who had been journalists or newspaper editors in Europe and wanted to renew the publication of an older paper in Israel. This was the case with the bi-weekly “Yidishe bilder” (Jewish photographs), which was founded in a DP camp in Munich immediately after the Holocaust, and the monthly “Lebns-fragn” (“Life Issues”) published by the Jewish Labor Bund.

Some editors of private Hebrew newspapers reached out to these new immigrants from Eastern Europe as well, by publishing separate Yiddish editions. One of these was the weekly “Veltshpigl” (“World Mirror”) – a Yiddish version of the sensational anti-establishment magazine, “HaOlam Haze” (“This World”).

But these privately owned newspapers were in the minority. The overwhelming majority of publications in Yiddish were issued by public organizations and institutions, such as Israel’s national trade union center, Histadrut, or by political parties who were interested in reaching out to Yiddish readers, especially the immigrants, because throughout the 1950s the Yiddish-speaking public was regarded as highly literate, making it attractive to publishers looking for political or financial gain. Of course, to attract that audience and hold its attention, these had to be quality papers with a range of content, including literary and cultural content. In paradoxical fashion, then, many of the same people and organizations that were opposed to Yiddish for ideological reasons actually contributed to the development of a vibrant Yiddish press in Israel.

Many of the earliest Yiddish newspapers in Israel were published by organizations with a radical left orientation that had promoted the Yiddish press back in Europe. But soon the country’s hegemonic political parties also began to recognize the importance of the Yiddish-reading public as a target for their propaganda. The first of these was the ruling party, the democratic socialist party, Mapai.

On January 7, 1949, even before “Letste nayes” was founded, Mapai began publishing its own semi-weekly newspaper in Yiddish, “Dos vort” (“The Word”). The title was a precise translation of Davar, the Hebrew name of the daily newspaper published by the Histadrut. The public understood full well that this new Yiddish paper was representing Mapai.

On January 25, 1949 the first elections to the transitional Israeli Parliament (the body that preceded the Knesset) took place. Mapai, the strongest political party in pre-state Israel and the ruling party in the early years of the state, needed a platform for its labor-oriented political message. “Dos vort” was initially meant to serve that function in those elections. The Mapai editors weren’t subtle about their intentions. Alongside its logo, each issue had a picture of the letter aleph – the same letter that appeared on Mapai’s ballots.

After the elections, “Dos vort” continued to appear twice a week for almost two years, essentially becoming a regular Yiddish newspaper. In February 1951, “Dos vort” expanded to six pages, added photographs and began to appear three times a week on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. Another sign of its development into a regular Yiddish paper came in January 1952, when the editors added a serial novel to its pages. So this was how Mapai, whose leaders held the reins of power in Israel and spearheaded the country’s militant Hebraistic policy, became the first public body in Israel to publish a Yiddish newspaper.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. In 1953, Mapai decided to launch a second Yiddish paper, “Di tsayt” (“The Time” ), which also came out three times a week – Sundays, Mondays, and Tuesdays, precisely those days that “Dos vort” was not coming out. It was obvious that this wasn’t a new paper at all. Essentially these two papers were complementing each other, in effect transforming it into a full-scale daily. Its front page carried a notice informing readers that, in fact, “Di tsayt” and “Dos vort” had the same editors and writers.

Despite this continuous catering to Yiddish readers, even Mapai leaders began to feel that they weren’t doing enough, especially since the legendary editor and owner of “Letste Nayes” – Mordkhe Tsanin – didn’t stop criticizing both Mapai and Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion for their politics. It was then that Mapai decided to try to create a higher quality Yiddish newspaper, but its leaders simply couldn’t find a skilled editor. In 1960 the party bought “Letste Nayes” from Tsanin, while keeping him on as editor. Though the purchase was never made public, it meant that the ideologically Hebraist party now owned and ran Israel’s most important Yiddish newspaper. It continued to do so for over thirty years.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO