How I, a Chabadnik, discovered Chaim Grade’s novels

Courtesy of the Newfield family

In the Chabad yeshiva in Crown Heights, where I was a student in the early 1980s, Yiddish literature was non-existent.

Sure, we spoke Yiddish in school and we read the text of the Rebbe’s Yiddish sermons, but Yiddish literature was never mentioned. Then again, we didn’t read English literature either. We studied the Torah, Talmud, and Jewish law all day, every day, including Sunday. Our school, Tents of Torah, was founded in 1956 with the express purpose to be the first (and only) yeshiva in America to teach its students a pure torah curriculum. And so they did. By the time I came around, the yeshiva had 1,000 students, from pre-k to post seminary.

Year after year, I sat with my fellow classmates repeating the Biblical verses with their Yiddish translation. The truth was, many of us didn’t really understand either Biblical Hebrew or Yiddish. We spoke English at home and between ourselves. But Tents of Torah refused to allow English to be spoken in the classroom. The running joke was, Tents of Torah graduates were illiterate in three languages, Hebrew, Yiddish and English.

Once, my 11th grade teacher tried to explain to us a difficult Talmud passage in English, as Yiddish wasn’t his first language. All of a sudden the principal opened the classroom door. Our teacher quickly switched back to Yiddish.

In 1999, when I was 20, I got a summer job at a Chabad outpost in the Sydney suburb of St. Ives, Australia. My main tasks were reading the torah in shul, leading services, and giving bar mitzvah lessons to local public school children. Since our summer is their winter, it was frigid cold when my friend and I drove to the synagogue each morning at 6:30 am. We opened the doors, set up the prayer books, and led the service. By 7:30 am the davening was over and the minyan dispersed.

One morning, after the davening, I went down to the basement of the rabbi who led the youth group and discovered a crate of books in the closet. Among them was a paperback copy of Chaim Grade’s “Rabbis and Wives.” A blurb by Eli Wiesel on the back cover of the book read: “One of the greatest – if not the greatest – Yiddish novelists. Surely he is the most authentic.”

I had heard of the Yiddish writers I. L. Peretz and Sholom Aleichem, since my non-observant paternal grandmother was a Yiddishist and loved reading me their stories, especially Peretz’s “Bontshe Shveig,” and Sholem Aleichem’s “Tevye Der Milkhiker.” But Chaim Grade’s name was foreign to me.

I decided to take the book home with me.

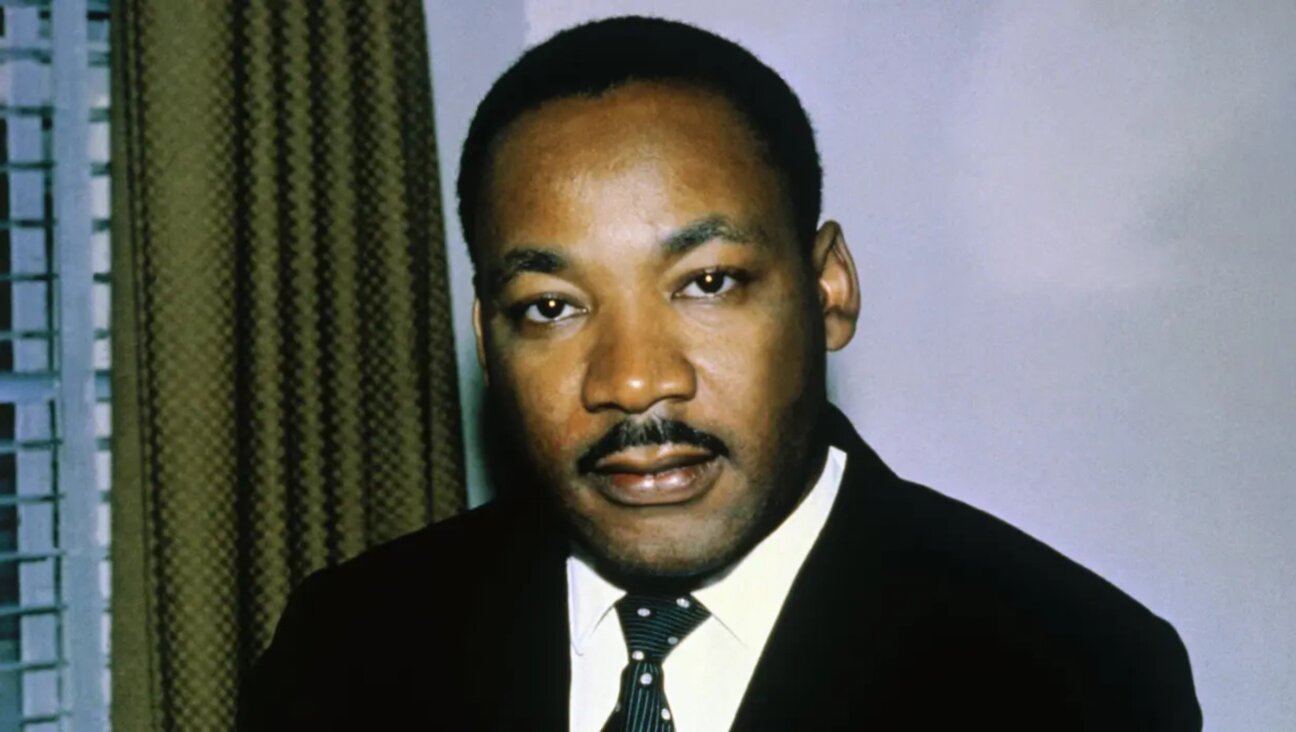

Yossi Newfield, with Chaim Grade’s book, “Rabbis and Wives”, in Sydney, Australia, 1999 Courtesy of the Newfield family

That night, I opened the book, which contained three novellas. From the first page of the first story, ‘The Rebbetzin,’ I was hooked. It was as if I finally found someone who understood my many questions and doubts.

Ever since I had entered the yeshiva, I was torn between what I was taught inside its walls and what I saw outside. In the yeshiva, I was taught that studying Torah was superior to any other kind of study. As the Yiddish song says, “Toyre iz di beste skhoyre – Torah is the best merchandise.” When I was very young, my mother used to sing this to me every night at bedtime. But at the same time, my father was a physician; his Harvard Medical School diploma proudly hung in his small home office. Eventually, my mother banished his small office to the dilapidated basement, lest his secular books and degrees remind my three brothers and me that we weren’t being taught English properly. Still, l knew he didn’t graduate Harvard by studying Torah. He grew up in a secular Jewish family, excelled at public school, went to Columbia College, and then went to Harvard. Halfway through medical school, he discovered Chabad and upon his return to New York joined the community. If toyre iz di beste skhoyre, why did my father spend his life practicing medicine?

Year after year, as I sat bent over the Talmud, tractate after tractate, I couldn’t seem to shake these questions off. Is the Torah the only knowledge worth attaining, or is there other wisdom, too? What would I do for a living once I finished my yeshiva studies? I wouldn’t even have a high school diploma, so getting into college would be out of the question.

I now researched all I could about Chaim Grade. He grew up in pre-war Vilna, and attended the mussar yeshiva of Nevardok. But the allure of the secular world was too strong. He eventually abandoned the yeshiva, joined the Yiddish literary group Yung Vilna, and became a writer. Nevertheless, his years in the yeshiva took their toll. For the rest of his life, he wrote extensively about his yeshiva experience. He desperately wanted to free himself from his yeshiva mindset, but couldn’t. Unlike I. B. Singer, who wrote on the American Jewish experience and translated his own short stories and novels into English, Grade wrote only on his pre-war yeshiva experiences, and only grudgingly allowed some of his prose novels to be translated into English. His refusal to accommodate his American readers probably cost him the Nobel Prize. He knew this, and bitterly resented Singer’s getting the prize as well as his subsequent success. But there was little Grade could do to change his nature. Even fifty years after leaving the yeshiva, he remained chained to its front door.

As soon as I returned from Australia I went to the main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library and found the two volumes of Grade’s novel, “The Yeshiva” (the English translation of his magnum opus, “Tzemakh Atlas”) in its basement stacks. I borrowed the first volume, went home and began reading.

Although the volume was 400 pages long, I finished it in a week’s time and was left deeply shaken. The struggles Grade so masterfully described between faith and doubt, between Torah and the world, in his words, di kloyz un di gas, were my own. The main protagonist of the Yeshiva, the yeshiva principal Tzemakh Atlas, followed the Torah but doubted the existence of its Giver. He was torn between the Torah’s demands and his own needs and desires.

Until then I had always taken great pride in my Talmudic learning. I was looked up to by my family, friends, and teachers and felt deeply connected to the long chain of tradition. But I knew that if I continued on this path, I would never be able to follow my father into the field of medicine. In terms of secular education, I was illiterate. As much as I enjoyed the give and take of the Talmud and rabbinic codes, I wanted to be a professional. Yet my own father was the one who put me into a yeshiva that taught nothing besides the Talmud and Jewish law. It was very confusing.

I wanted to check out Volume 2 of “The Yeshiva” to see how the story ended, but I knew that if I did, I might end up like Grade himself, outside the yeshiva’s insular world. The thought of abandoning the yeshiva horrified me. The intense friendships I had forged through years of khevruse, one-on-one study with a Talmud partner, was my home.

Over the next three years I read Grade’s “Der shtumer minyen” in Yiddish, and “The Agunah,” “The Well,” and “My Mother’s Sabbath Days” in English, but I still couldn’t bring myself to check out Volume 2 of “The Yeshiva.”

One spring day, as the holiday of Shavuos was approaching, my family decided to spend the holiday at our great-aunt’s boutique hotel in the Hamptons. In the early 1970’s, she had saved an annex to the historic Irving Hotel from demolition and renovated its 70 guest rooms. The hotel sat on five acres of land, just a stone throw away from the village. Initially, we didn’t visit the hotel for the Jewish holidays, as there was no synagogue in town. But in the late 1990s, Chabad set up an outpost across the street so we began spending the holidays there. With nine children, we usually set up camp in the main guest house called The Terry.

Knowing Shavuos was a two-day holiday without access to radio or TV, my mind kept thinking about Grade’s second volume of “The Yeshiva.” I needed something to read over the holiday, as we lounged under the sweeping cherry blossoms on the main lawn. The temptation to see how the story ended was too strong. I checked out the book from the local library.

There’s an old Jewish custom to stay awake all night studying the Torah on the first night of Shavuos. I was planning to do it this time as well. But by the time the holiday meal ended I was exhausted. It was already 11:30 pm, and most of the kids had gone to bed, as did my father. Not wanting to make the trek back to the synagogue alone, I curled up on the couch with Grade’s “Yeshiva.” As my eyes kept closing, I forced them open and read on. By the time the morning sun rose, I had finished the book and I knew that there was no going back to the yeshiva. As I dozed off I realized that Moses may have given the Jews the two tablets, but Grade gave me the two volumes of “The Yeshiva.”

Yossi Newfield (right) with his father, Dr. Shlomo Newfield, and a brother, Zalman, at his father’s 70th birthday in 2021 in Glen Cove, New York Courtesy of the Newfield family

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO