An Echo of Jewish Lublin through Yiddish Fonts

“Normally, a poster would not include so much empty space. But any poster about Lublin must contain empty space,” Robert told me.

I was standing in the print shop of Dom Słów or The House of Words in Lublin, Poland, next to visionary printer Robert Sawa in his signature ink-stained apron, his long graying hair pulled back in a ponytail.

Robert was going to create a poster for an international seminar I was co-chairing with Dominika Majuk for memory workers (people working — often in the cultural sector — to preserve the memory of a group or individual who is no longer present) from all over Europe. The seminar was organized in partnership with Germany’s EVZ Foundation, whose mission it is to keep alive the memory of the injustice of Nazi persecution and to work for human rights and international understanding.

The House of Words (Dom Słów in Polish) is a printing house and cultural center dedicated to the printed word. It is part of Brama Grodzka-Teatr NN — a municipal institution in Lublin committed to preserving the memory of the Jews of Lublin. They print materials on old printing machines, like a rare German linotype machine from the early 20th century. I had worked closely with Brama Grodzka for several years, but was less familiar with The House of Words.

The poster was to commemorate this inspiring gathering of people who are devoting their lives to remembering the victims of Nazism: Jews and Roma, forced laborers and others.

As we stood in the basement of Dom Słów, surrounded by fonts, old machines, and the smell of ink and grease, Robert gave me a peek into his creative process. He told me he was taken aback by the length of the seminar’s title: “Local Perspectives on Difficult Histories: An Open Exchange for Best Practices in Memory Work.” He described this as a “dramatic and sad situation.”

He decided to relegate the title to the bottom part of the poster and leave a big space above with only our logo and our quote taking up small parts of that space.

By noting that a “normal” poster would not include so much empty space but that any poster about Lublin must contain empty space, Robert taught me how deep the work of remembrance goes in Brama Grodzka. Even the typographer becomes a memory worker.

It was a statement of a profound yet simple truth: Most of the Jewish quarter of Lublin had been destroyed by the Germans after they deported 28,000 of Lublin’s 43,000 Jews to the Bełżec death camp. House by house, street by street, the area at the base of the castle was destroyed. Lublin has a hole in the middle of her heart where the Jews should be, and a literal empty space where my ancestors and those of my fellow Lubliners had lived for centuries. That emptiness must be recognized.

Robert explained that the words in the title of the seminar were like characters in a play and the fonts were the actors playing the parts. The first actor to be cast in a leading role was the word “work”. For this,he used one of the oldest fonts, called Renaissance.

“Renaissance has gone through a lot,” Robert told me. “You can see all its scars. Fonts don’t lie. They can’t lie. You can see all their holes and imperfections. They tell a story.” Who better to tell this story than these old letters, witnesses to memory?

According to Robert’s thinking, the word memory is a little younger than work but it is still played by quite an old font, a nameless one, like so many of the people who used to walk the streets of Lublin.

The logo for the seminar was the lamp that burns 24/7 in memory of Lublin’s Jews; the lamp at the top of the poster illuminates the empty space. And in very small letters is a quote by Brama Grodzka’s Deputy Director, actor and storyteller Witek Dąbrowski: “There is Light because there is Memory. There is Light but not Life.” This quote about Light sits under the lamp in the empty space.

Perfect, right?

Not yet.

At Dom Słów they make paper. The paper is made by a woman named Sylwia — often using materials she finds foraging in woods and meadows. Sylwia gave Robert some beautiful, rough pieces of thick paper that gave him an idea: Why not emboss the names of the non-existent streets in the empty space? This would create a ghost-like presence; the street names would be visible only when held up to the light at a certain angle, and only if the person looking had the patience and the desire to see them.

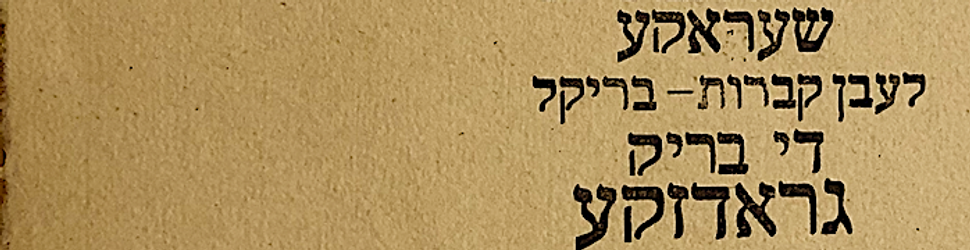

Yiddish fonts are part of the Dom Słów collection, and he had the idea to do this in Yiddish, but he did not feel he had the right or the knowledge to put those Yiddish letters together. None of the people who work at Brama Grodzka are Jewish, so he asked me to help.

I gathered the Yiddish spellings of those Jewish streets from a researcher at Brama Grodzka, Pior Nazaruk, who had taken two intensive Yiddish summer courses at YIVO. I don’t know why it was so gratifying, picking out the letters one by one to form the names of the streets and places that made up the landscape of my ancestors’ city, Lublin. I picked the letters out of an old typography box and formed the names in Yiddish—backwards so that Robert could print them forwards. Forming names of streets that no longer exist: One that my great-great grandmother Nechama Borensztajn was born on — Nadstawna Street. One that my mother and grandmother were born on: Szeroka Street—an iconic street in Jewish Lublin that no longer exists. In its place stands a parking lot.

And the strangely named Farkakte Brom, or Dung Gate. According to Piotr Nazaruk, “Though officially called Podzamcze Gate, in Yiddish it was known as Farkakte Brom or Fardoste Brom, both meaning the same thing. It is hard to say why, maybe it was indeed used, even in some distant past, as a place where people used to throw away waste. The Polish name Brama Zasrana also existed and meant the same thing.”

There was something sacred in the act of physically putting the letters in place to form Yiddish words in a place where the Jewish culture was wiped out. They have not been together in those combinations for a long time. I imagine if they were aware they would be grateful that someone remembers.

After I laid out the street and place names, Robert printed them out with ink so we could check for mistakes. Before pushing down the lever on the old machine to ink the fonts he said in Polish:

“They’ve been waiting a long time.”

“They?” I thought to myself, not being sure if I had understood. “Who was he talking about?”

And then it hit me. He was talking about the fonts. These fonts, which had miraculously made it out of Europe, and gotten to Israel, had now come back to Poland, thanks to a donation by a couple in Israel, Jacob and Shoshana Schwartz. The fonts had not been used for perhaps eighty years. Ironically, the first time they would be used now would be in order to recall those distant, now-destroyed places where our families used to walk. He paused before dousing them with ink.

Pointing to the poster, Robert used the term “podzamcze,” which means “under the castle.” That’s the area of Lublin where the majority of Jews once lived; it was mostly destroyed by the Germans after they sent 28,000 Lublin Jews to Bełżec to be gassed. At first I was confused. Why is he saying, podzamcze and pointing to the poster? Then I realized he was pointing to the empty space on the poster and for him empty space and podzamcze were synonymous.

Robert explained that the poster with the embossed street names would remain in Lublin and that seminar participants would take home originals on regular, thin poster paper (each one printed out by hand and thus a unique original, not a copy) that did not contain the Yiddish street names. They would remember that they had seen the poster with the names here in Lublin; those streets exist only in memory, and, sadly, that is how it must remain.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO