Reclaiming my great-great-grandfather’s prayer book and the Yiddish world he lived in

Image by Gabriel Zuckerberg

Read this article in Yiddish

June 2020 through August 2021 was supposed to be a gap year for me as I moved from my undergraduate to graduate studies. I didn’t plan for the pandemic, let alone its impact on my Jewish, scholarly and music communities. We were all forced to adapt to online formats, reshaping our interactions—and often, unveiling our honest opinions.

All the while, I’ve been relearning Judaism through the lens of Yiddish culture. Many in my generation who were raised in the Reform movement have moved away from it, realizing its assimilated, German-Jewish disposition and soft yet resolute adherence to Zionism.

But this doesn’t mean that we’ve rejected Judaism. In fact, I was raised in a community where the word “secular” doesn’t mean just non-religious, but rather non-Jewish; in other words, the Christian default.

It wasn’t till much later that I learned the history of the Jewish Labor Bund and its commitment to secularism, Yiddishism and non-Zionism. In Hebrew school we also learned, if implicitly, that Hasidim and the Neturei Karta are fanatics. Hebrew school never taught me about the beginnings of the Hasidic movement and its subversively populist bent. My peers and I were fixed into a gray area, given little insight into why the gray was so hazy. So now, more and more of us want to reconnect to those roots that have almost withered, secluded by the norm.

This past May, my father suggested that I drive from my apartment in Somerville, Massachusetts, to visit my grandparents in New York for Mother’s Day weekend. Coincidentally, all four of my grandparents had recently relocated to the same neighborhood in Somers, New York, and my older sibling, Jules, was planning to make the same visit. I arrived in New York and, for the first time in over a year, enjoyed a series of unexpectedly typical family meals, with much discussion about our family history.

As it turned out, Jules was just as eager to learn about our grandparents and great-grandparents as I was, especially about the culture and politics of our ancestral Pale of Settlement, in Czarist Russia. Our conversation eventually led to a fervor to learn our heritage language, Yiddish. A tad baffled by this, our 91-year old Grandpa Fred recalled that, some years ago, a relative of ours had donated a makhzer (holiday prayerbook), that had belonged to his own grandfather (my great-great-grandfather), Nathan Cohen, to the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachussetts.

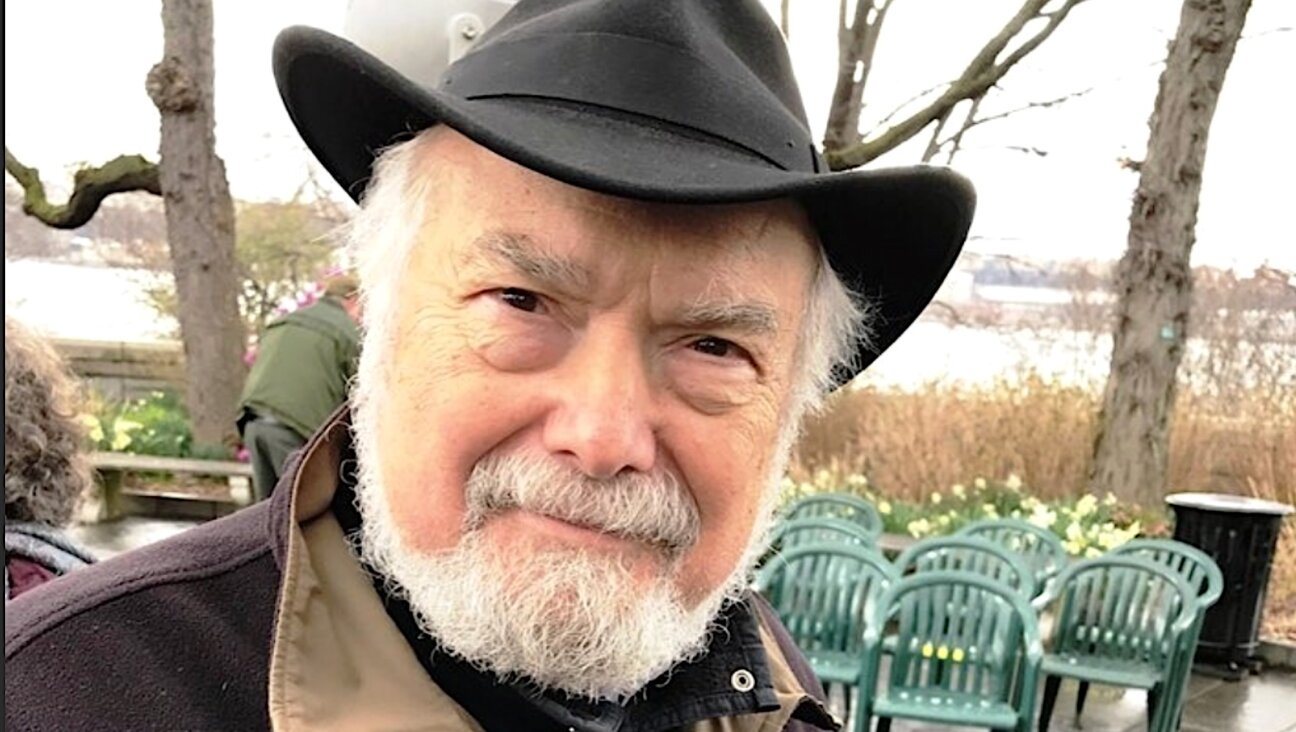

My great-great-grandfather, Nathan Cohen Image by Gabriel Zuckerberg

Grandpa Fred told me that Nathan Cohen was named Nokhim Akhitovich before immigrating through Ellis Island. In my own genealogy research, I discovered that Nathan was born in the shtetl of Yezne, known today as Jieznas, Lithuania. Fred remembers him fondly because he had had a tense relationship with his own mother and no connection at all with his father, so his grandfather, Nathan, stepped in as the parent Fred needed. Though Nathan died 72 years ago, he and I are now reconnecting in two ways — through my grandfather Fred and through Nathan Cohen’s prayer book.

The prayer book was issued by a venerable publishing house in Vilna in 1894-95 Image by Gabriel Zuckerberg

I decided then that I had to find this family heirloom. As my friend, Sarah, suggested, I emailed the Yiddish Book Center’s bibliographer and editorial director, David Mazower, who replied just eleven minutes later. Mazower told me that he was thrilled to hunt down my ancestral makhzer. Two days later, he emailed me that a librarian at the Yiddish Book Center had found the book! Turns out that it’s a special prayerbook used for the spring holiday of Shvues (the Yiddish pronunciation of Shavuoth), issued in 1894-95 by the venerable publishing house in Vilna — Rosenkranz & Schriftsetzer. I was struck by the serendipity that I had first contacted Mazower just around the end of Shvues.

So even before the makhzer arrived at my house, I had already made my decision: Next year, when Shvues rolls around again, I’m going to take my great-great-grandfather Nathan’s prayerbook to shul with me, reviving it from its previous artifact status and breathing new life into it.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO