Why the rabbi cursed his congregation

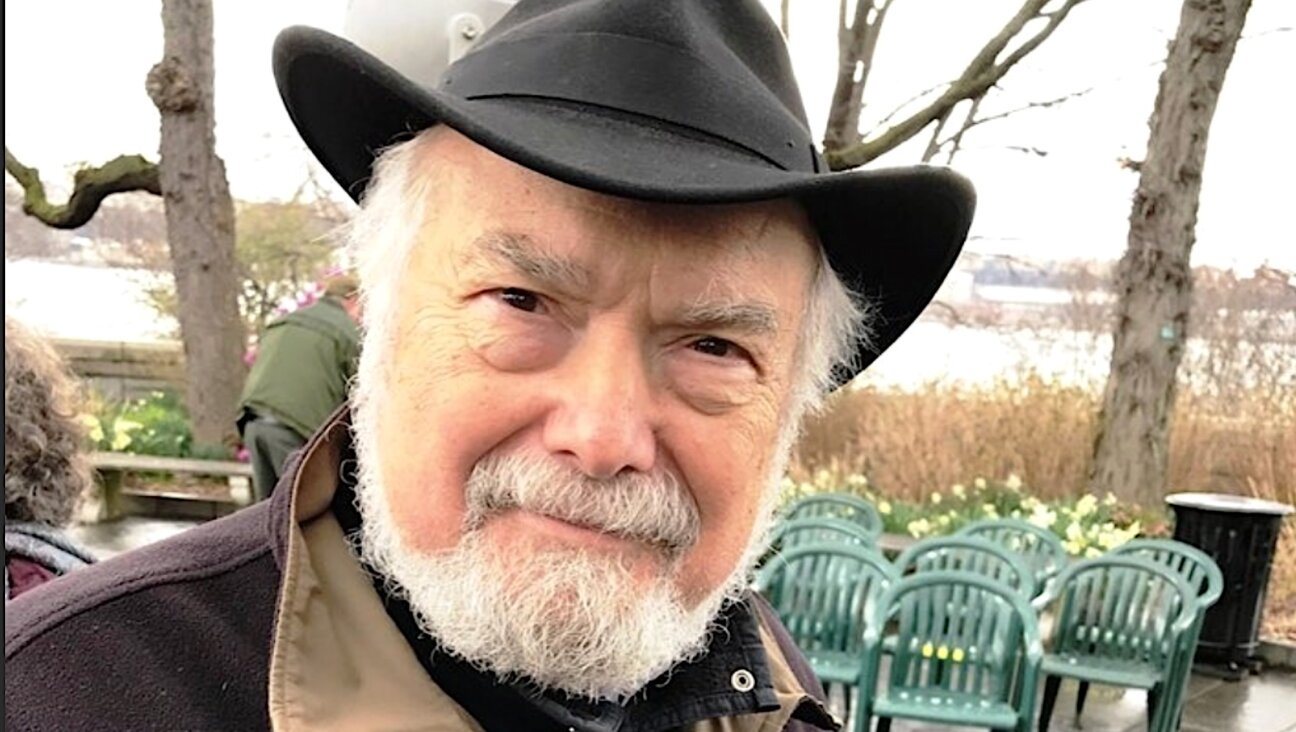

Image by Rukhl Schaechter

Read this article in Yiddish

Last September, the Forward published an article about a very curious incident in 1926, in which the rabbi of a Yonkers Orthodox synagogue opened the aron kodesh, the ornamental closet in the synagogue housing the Torah scrolls, and cursed the congregation.

The author of that article, Nancy Klein, whose parents joined the synagogue, Ohab Zedek, several years after the incident, remembers hearing the grown-ups whisper about the scandal but was never able to ascertain why the fiery Hungarian-born rabbi, Philip (Shraga) Rosenberg, resorted to such a dramatic demonstration.

Mysteriously, Rabbi Rosenberg then swapped pulpits with his son, Rabbi Alexander Rosenberg, in Cleveland, Ohio. The father stayed in Cleveland for the rest of his life and his son became a popular respected rabbi, not only in his own synagogue, but throughout the New York area.

Eager to learn more about this compelling story, I contacted Rabbi Philip Rosenberg’s descendants, but they, too, didn’t know the details. Rabbi Berel Wein, a historian who had a close relationship with the son, said in an interview that the elder rabbi swapped pulpits with his son in order to give him the opportunities that the New York area would afford a much younger rabbi. But as Mrs. Klein hints in her article, Rabbi Philip Rosenberg’s choice to leave Ohab Zedek was not exactly voluntary.

Some important clues to this mystery lie in a letter written to an officer on the board of Ohab Zedek in January, 1923. The letter was from Rabbi Mordechai Leib Winkler, a respected Orthodox rabbi overseas, in the city of Mad, Hungary. Apparently, the board member, a Hungarian-born dentist named Dr. Simon Miller, had asked Rabbi Winkler whether a synagogue could appoint a rabbi who had previously served as the rabbi of a “Status Quo” community – the name given to a community that chooses not to affiliate with the Orthodox establishment. Rabbi Winkler responds: “I cannot hold back my great astonishment. What was this congregation thinking when it gave him the rabbinic position, after this rabbi served for eleven years as the rabbi of a Status Quo community?”

What exactly was a Status Quo community, and why was Rabbi Winkler so opposed to it? In Hungary, in the late 1800s, a schism raged between the traditionalist Orthodox rabbis and the modern “Neolog” movement. Some communities chose not to affiliate with either the Orthodox or the Neolog movements, calling themselves Status Quo communities. Many of Hungary’s leading Orthodox rabbis banned affiliation and cooperation with both the Neolog and the Status Quo communities. It didn’t matter if the members of the Status Quo synagogues were observant Jews. Because they didn’t affiliate with the established Orthodox movement, they were deemed beyond the pale.

Though not mentioned by name, there is no doubt that Miller’s question to Rabbi Winkler was about Rabbi Phillip Rosenberg. Before immigrating to the United States, Rabbi Philip Rosenberg had indeed been the rabbi of a Status Quo community in Hungary, a position he inherited from his father-in-law.

In those days, though, the term “Orthodox” meant different things in the United States than it did in Hungary, and by any American standard or definition, Rabbi Rosenberg was an Orthodox rabbi. Though it isn’t surprising that the stringent Rabbi Winkler ruled against Rabbi Rosenberg, it is surprising that he was consulted in the first place. That brings us to Simon Miller himself, the board member who wrote the letter.

In addition to being a leader on the board of Ohab Zedek, Dr. Simon Miller (1887-1971) was also the founder and lay leader of a local Zionist organization as well as the founder, editor and contributor (under various pen names) of a rabbinic journal called Apiryon.

As it turns out, there was a debate that raged in the pages of Apiryon, in which Miller sharply criticized the stark self-separation of the Orthodox rabbis in Hungary from the other streams of Judaism in Hungary and Germany. So if Miller was so opposed to uncompromising, stringent rabbis like Rabbi Winkler, why did he bring him into the fray at all? Apparently, Miller knew that getting the support from Rabbi Winkler would help him engineer Rabbi Rosenberg’s ouster.

So why did Miller want to get rid of Rabbi Rosenberg in the first place? In Rabbi Winkler’s letter, there’s mention made of a disagreement that Miller had with Rabbi Rosenberg: apparently, Rosenberg wanted to decertify a local ritual slaughterer, against Miller’s wishes. Rabbi Rosenberg was also a strong supporters of the non-Zionist Orthodox movement Agudath Israel which Miller, a devoted Zionist, criticizes fiercely in his magazine.

To be sure, feuds between rabbis and lay leaders are nothing new. What was different in this case, and what apparently led Rabbi Rosenberg to curse not only Miller but the entire congregation, was that Miller had used a leading Hungarian rabbi to undermine Rabbi Rosenberg’s Orthodox credentials. To be fired is one thing; to be accused of impiety is something else entirely.

But there are several plot twists in this tale. First of all, the pulpit-swap that Rabbi Phillip Rosenberg engineered with his son was apparently not the first time that he had worked out a compromise to prevent the humiliation of being ousted as rabbi. When Phillip’s own father, who was rabbi of the town of Tasnad, Hungary, passed away in 1898, he, Phillip, became a candidate to succeed him. But some members of the community opposed his appointment and spread rumors that he was too modern. So he resolved the fight by offering to withdraw his candidacy in favor of his brother-in-law, this way ensuring that the pulpit would remain in the family. His pulpit-swap with his son 25 years later followed almost the exact same script!

Secondly, it seems that Rabbi Phillip Rosenberg, who had once been ousted for being insufficiently Orthodox, seems to have gotten the last laugh. His son, Alexander, ended up becoming not only very popular among his congregants, but was also widely praised for his work as administrator of the Orthodox Union’s kashrut division for over 20 years, where he helped end corruption in the kosher certification industry and made kosher food widely available to all American Jews. Secondly, just this past February, the OU appointed a new executive director, Rabbi Moshe Hauer, as its new executive director whose wife, Mindy, is Rabbi Alexander Rosenberg’s granddaughter! So as it turns out, despite the attempt to undermine Phillip’s Orthodox bona fides, two of his descendants rose to the top of the American Orthodox establishment.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO