Behind The Scenes On ‘Shtisel,’ Netflix’s Surprise Ultra-Orthodox Hit

Gone are the decrepit Mea Shearim streets of ‘Shtisel’. Image by Shtisel

This article originally appeared in the Yiddish Forverts.

On a recent Tuesday evening, more than 2,200 fans of the Israeli television show “Shtisel” streamed into Manhattan’s Temple Emanu-el to watch a lively stage discussion with three of the series’s leading actors and its producer.

The Israeli drama about an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family in Jerusalem, which was very popular with both secular and religious Israeli audiences during its two-season run from 2013 to 2015, gained a huge American following once Netflix picked it up and added English subtitles.

Since then, the show has become a prime topic of conversation at Shabbos tables across the U.S. and engendered several popular Facebook groups like “‘Shtisel’ — Let’s Talk About It” and “Shtisel Addicts.”

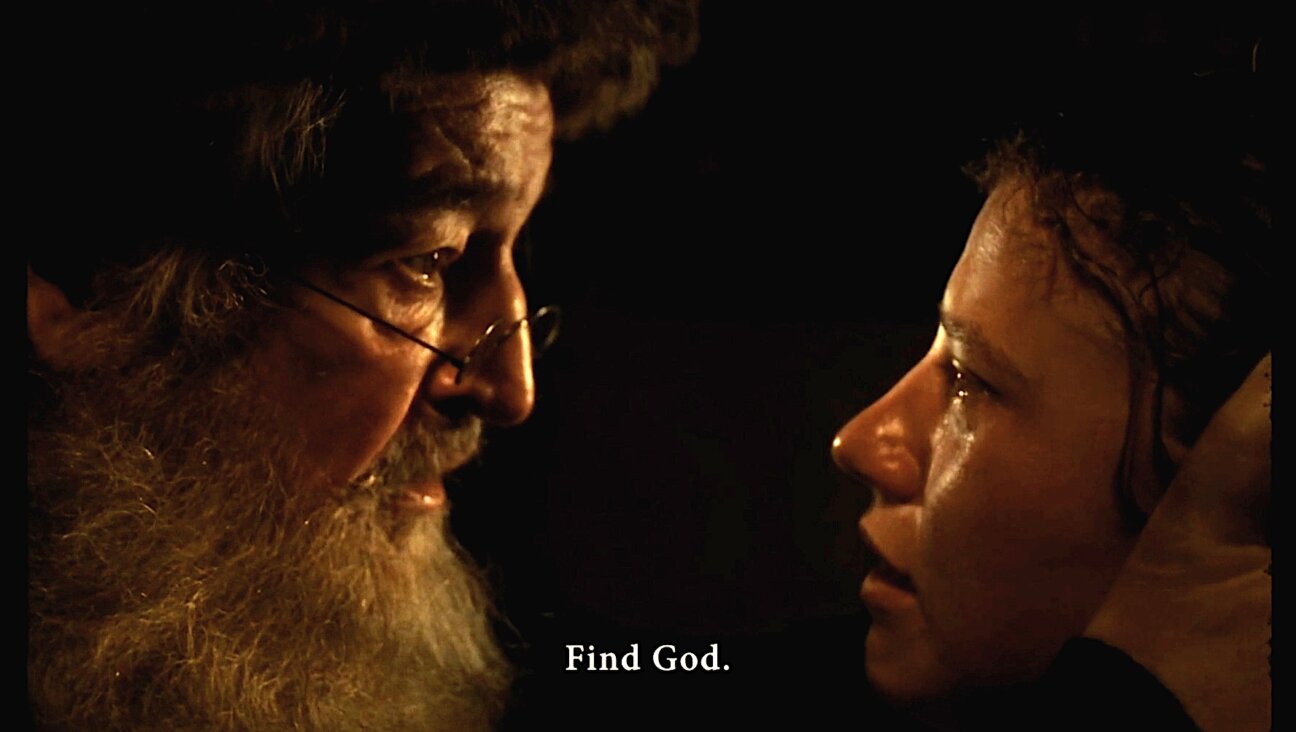

Dov Glickman, who plays Shulem Shtisel, and Michael Aloni, who plays Akiva Shtisel, during the program. Image by Rukhl Schaechter

In fact, tickets for the June 11 show sold out so fast that a second discussion was added the following evening to satisfy demand. All in all, about 4,600 people attended the two events, which were sponsored by the Jewish Week, the United Jewish Appeal and Temple Emanu-El.

The two panel discussions, as well as three others in Los Angeles and New Jersey, gave Americans a rare opportunity to hear the actors in “Shtisel” discuss their program in English. The mood among the attendees was one of excitement and anticipation; before the talk began, even strangers were striking up conversations, discussing the show’s characters and favorite episodes.

The four participating in the discussion were Doval’e Glickman, the actor who plays the patriarch, Sholem Shtisel; Michael Aloni (Kive, Sholem’s son), Neta Riskin (Giti, Sholem’s daughter) and producer Dikla Barkai. Ethan Bronner, senior editor at Bloomberg News, moderated.

Glickman was hilarious, acting out absurd moments on the set. One instance he particularly highlighted was a time when the show’s crew directed him through his earpiece to walk in and out of a religious book store in the ultra-conservative neighborhood of Mea Shearim. After the scene was shot, Glickman, who had been shouting to the invisible crew throughout the filming, asked the perplexed Hasidic bookseller why he didn’t react. His response? “Come next week, I’m getting some new books.”

Dov Glickman, who portrays Shulem Shtisel, answering questions. Image by Rukhl Schaechter

But Glickman also shared some serious moments. “You have to understand, I grew up on French and other European films, I was a man of the world,” he said. “But then every morning I was putting on beard and peyos [sidecurls] and all the clothes and suddenly it hit me: ‘Shtisel’ made me realize I’m a Jew.”

When Bronner suggested that Aloni’s character of Kive, who loves to sketch and gets slowly drawn into the Israeli art world, might want to leave the religious life altogether, Aloni vehemently disagreed. “No, Kive does not want to leave the Haredi world,” he said. “Think about it: The one time he forgets to lay tefillen he feels terrible. It’s just that he’s searching for inspiration.”

All four panelists emphasized their shock at the success of this modest drama about ultra-Orthodox Jews — and not just in Israel and the U.S. “One day, I was walking on a street in Brazil minding my own business,” Aloni said, “when suddenly I hear someone yell: ‘Hey, Kive!’ I turn around and there is this Brazilian guy grinning at me, saying: ‘Can I take a selfie with you?’ Turns out he was a local valet and wasn’t even Jewish.”

Riskin shared a number of insights she gained while learning to play Giti, a Haredi mother of four children. “When I came for the first meeting with my coach, I brought a pad full of questions,” she said. “I was sure she would teach me Torah. Instead she said: ‘No, I want to see you walk.’ So I walked from one side of the room to the other; the coach looks at me and says: ‘OK, I see we have a lot of work to do.’ We started doing walking lessons.”

Riskin learned that when Giti leaves the house, her goal is “not to be seen, to try to be invisible, like a ghost; make no eye contact; just go from Point A to Point B.”

The actress thought the writers did a brilliant job shaping Giti’s character, particularly after her husband, Lippe, runs away to Argentina. “In Homer’s ‘The Odyssey’, we follow the man on his adventures, not the woman who waits for him,” she said. “But here we stay with the woman left behind because her story is more interesting than following Lippe as he runs around with other women.”

Even more surprising, Riskin said, is Giti’s refusal to hear about what Lippe did after he finally returns and wants to confess all. “I couldn’t believe it!” Riskin exclaimed. “What do you mean she doesn’t want to know? But then I realized she has a plan. She doesn’t want pity. She wants to make a good shidduch for her children. By not considering his story important, Giti suddenly flipped the power balance between them. He’s now the weak person; she’s the strong one.”

Throughout the discussion, the four participants repeated how stunned they were that that “Shtisel” was a hit with secular Jews. But Aloni pointed out that he was even more impressed that Haredis were watching. “They simply used WhatsApp to download it,” he said. “It was an amazing thing for them, because here they saw themselves.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO