After I Witnessed A Tragic Accident, An Odd Torah Phrase Gained New Meaning

Image by iStock

This article originally appeared in the Yiddish Forverts.

Whether we notice it or not, we’re often faced with small ethical moments forcing us to decide quickly how to react. A young man steps into the subway car, begging for money or something to eat. You can ignore him, or you can fish out the banana that you had packed in your bag for an afternoon snack.

Or a neighbor has recently undergone chemo and although you know visiting her is the right thing to do, you hesitate because you just don’t know what to say.

But sometimes something happens in which your decision can literally determine the fate of a person’s life. That’s the story I’d like to share with you.

It happened on a Shabbos morning in early December. Walking home from my synagogue in Riverdale, New York, I began thinking about an unusual phrase a friend of mine had pointed out to me from that morning’s Torah reading, Vayeshev. The phrase – “Haker-na!”, a command that means “Recognize this!” – appears only twice in the entire Bible, and both times, oddly, in that morning’s reading. Like a student of literature eager to understand the author’s meaning of a mysterious turn of phrase, I began wondering what this expression could mean.

The first time we read the phrase “Haker-na!” is in Chapter 37, Line 32, right after Joseph’s brothers tear his fine robe from his back and sell him to a group of Midianite merchants. In order to prevent their father, Jacob, from discovering what they had done, the brothers dip Joseph’s robe in goat’s blood and concoct a story that a wild animal had devoured him. They present the bloodied garment to their father with the words: “We found this. Haker-na! Recognize now whether this is or is not your son’s robe.”

The second time we read this phrase is in the same Torah reading but later – years later, in Chapter 38: Joseph’s brother, Judah, spends the night with a prostitute, unaware that the disguised woman is his daughter-in-law, the widow, Tamar. When Judah discovers that his daughter-in-law is pregnant, he is ready – like all the others – to have her punished to death, until she cleverly proves that he is just as guilty as she. Standing before the judges who have sentenced her to death, she draws out the three objects she had asked Judah to give her as collateral when they slept together: his signet, his cloak and his staff. She displays the three articles before him and the judges and says: “Haker-na, recognize this!”

Reflecting on this curious phrase, I suddenly spied, just one block from my home, a nearly bald elderly man lying in the middle of the street, close to a minivan. He was barefoot, his head and legs were bloodied and two young women, apparently in their 20s, were kneeling by his side. One of them had an orange streak through her dark hair and was yelling: “Please, answer me! Say something!” The second woman was speaking into her mobile phone, apparently with the dispatcher at 911, saying: “Yes, I think she’s breathing but I’m not sure!”

That’s when I realized the injured person was a woman. It was also then that I noticed a curly blond wig leaning against the windshield and speculated that this had probably fallen off the injured woman’s head during the accident, although exactly what had happened was still unclear.

Suddenly, the woman on the telephone looked up at me and asked hopefully: “Are you a doctor?”

“No, I’m sorry,” I replied. Meanwhile, a crowd had begun to gather around the three women, all waiting for the ambulance to arrive. 5 minutes passed, 8 minutes, 10 minutes, nothing.

Suddenly, I remembered that the Jewish ambulance service, Hatzolah, often comes faster than a city ambulance, or at least it does in Riverdale. I didn’t know the phone number by heart so I ran home and called the number. They asked me where the accident had occurred, thanked me and hung up. I ran back to the scene and saw a man wearing a yarmulke and a suit running in the direction of the injured woman – a Hatzolah volunteer. 30 seconds later, a fire truck and police car arrived, and finally, the ambulance. The woman with the orange streak in her hair was escorted, sobbing, into a second car.

I went home, shaken. Later I learned from local news reports that the minivan had indeed hit the woman as she crossed the street. Sadly, she didn’t survive the trauma and died on the way to the hospital. Her name was Beatrice Kahn, she had just celebrated her 89th birthday the day before and had just begun attending a folk-dance class. “This was not her time to go,” her daughter, Judy, told reporters.

Hearing the bitter news, my heart grew heavy and quickly turned to anger at the New York ambulance service for having arrived more than 15 minutes after they were called. It was then that I realized that this tragedy was my own “haker-na” moment. Most of us aren’t physicians or health professionals. We don’t know how to give first aid to a wounded victim, so we rely on others to do it. But sometimes it happens that we can do something. When that young woman turned to me, asking: “Are you a doctor?” I should have understood that in this case, I could have helped. I could have immediately called another ambulance service that I knew often came faster than the city ambulance. Who knows? Maybe that difference of 5-8 minutes could have altered the fate of Beatrice Kahn’s life.

Sometimes we have no choice and need to rely on others to do what’s necessary. But every once in a while, we need to take the initiative. The lesson here? Don’t be shy. Recognize your own strength. Haker-na.

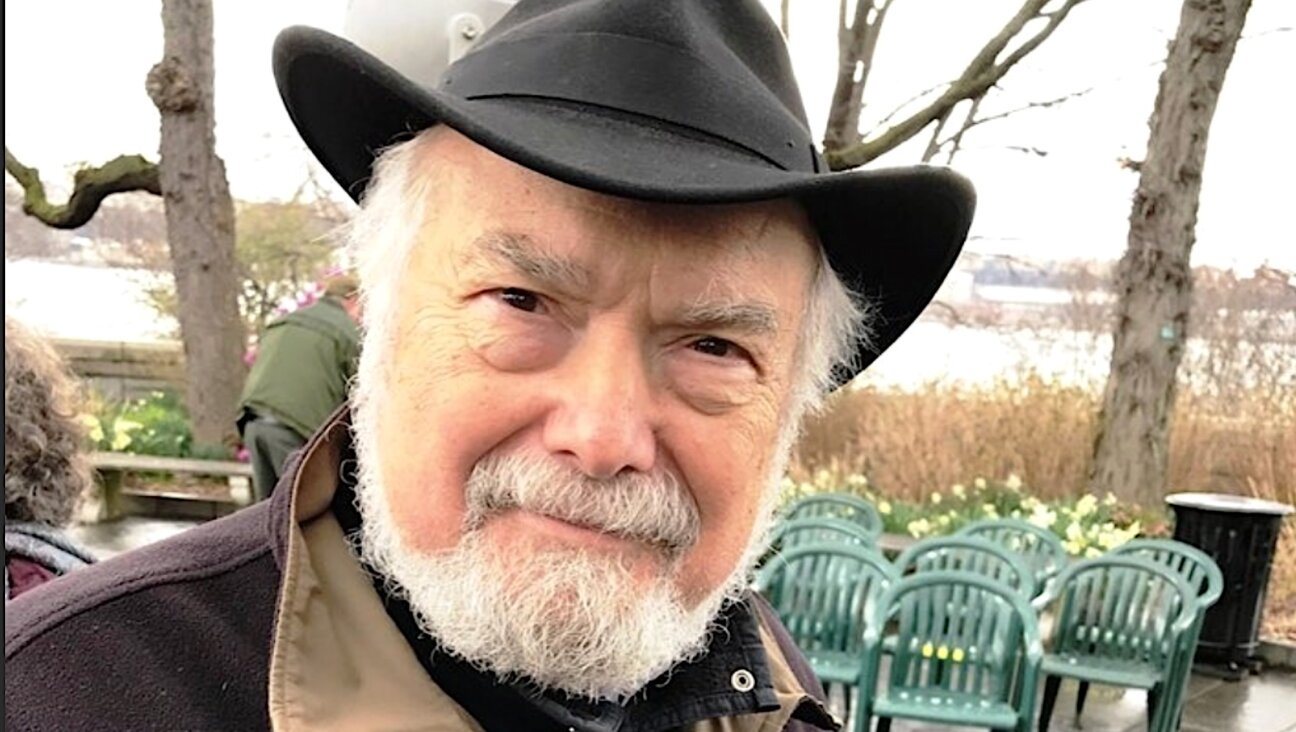

Rukhl Schaechter is the editor of the Yiddish Forverts.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO