Banning Carlebach Melodies Would Be Self-Defeating

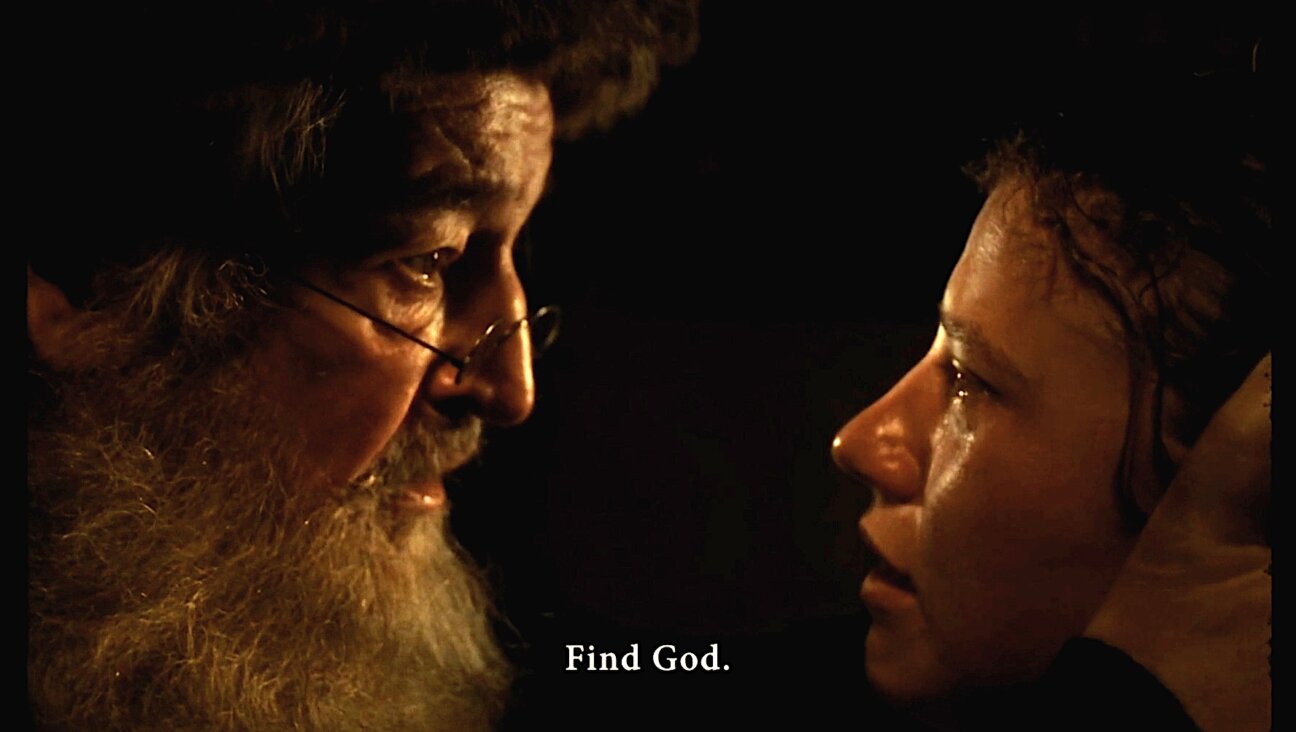

Rabbi Carlebach singing at a wedding. Berkeley, California, 1973. Image by Getty

This article originally appeared in the Yiddish Forverts.

As the list of accusations of sexual harassment against well-known figures continues to grow, it isn’t surprising that charges against spiritual leader and composer-singer Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach have resurfaced, leading some of his accusers to call for a ban of his melodies, many of which have become an integral part of the Jewish prayer service.

Throughout his 40-year career, Carlebach was like a rebbe to young American Jews seeking a more spiritual path in Judaism. The movement had grown out of the general mood in the 1960s and 70s, in which the younger generation rejected the conventional institutions of their parents, including their synagogues which they viewed as too formal, inflexible and focused on material needs.

As a result, a new kind of “synagogue” appeared: the Havurah. Here, young men and women would gather in a modest room on shabbos and yom-tov to pray, sometimes even while sitting on rugs. Reb Shlomo, as his followers called him – the charismatic scion of an esteemed rabbinic family – would often lead these informal services where he inspired worshippers with his heartfelt sermons, spreading a message of love and kindness towards fellow Jews or to anyone in need. He also set the prayers to lovely niggunim that he had composed himself, and that were so easy to learn that over the years they became a familiar element in communal Jewish prayer, particularly on Friday nights when welcoming the Sabbath. Although Carlebach passed away in 1994 his niggunim can now be heard in tefillah services ranging from ultra-Orthodox to Reform, throughout the US and Israel.

For those who say they were victimized by Carlebach, it can be jarring sitting in shul listening to people singing his melodies and it’s understandable why they and their supporters feel it’s inappropriate to honor a man accused of sexual misconduct.

As one who has written about accusations of sexual harassment against another well-known Orthodox rabbi, I certainly don’t mean to whitewash the issue. If Carlebach were alive today, I would absolutely support the accusers’ right to report their claims.

But when people demand that we stop singing his tunes in solidarity with the accusers, I have to disagree. First of all, Carlebach is no longer here to defend himself. I’d also like to believe that if he were alive, and did indeed wrong these women, he would take full responsibility and begin a serious process of healing and atonement.

Secondly, boycotting his melodies simply doesn’t make sense. As a child of Holocaust survivors I’ve often heard relatives and friends vowing never to buy a German car or any product produced by a German firm. Considering that most German goods are of high quality, this kind of pledge has always puzzled me. For years, I enjoyed a dishwasher produced by the German company, Bosch. I figure, if Bosch makes good dishwashers, why shouldn’t I benefit from them? If I did refuse to buy high-quality products simply because they were produced by the Germans, I’m only punishing myself.

Thirdly, and this is a point well-made by my colleague, Laura Adkins, the hundreds of melodies that Carlebach brought into the davening has inspired thousands if not tens of thousands (including myself) to experience the prayers on a visceral level instead of just reciting text. For many Jews, it’s one of the main reasons they began attending shul more often.

Finally, Carlebach made it cool to use the traditional Ashkenazi pronunciation during the service. In the 1960s and 70s – a time when Hebrew school teachers were constantly changing the Yiddish names of their students to Hebrew (Berl and Faige became Dov and Tzipora); in a time when the Ashkenazi pronunciation would elicit laughter outside the Haredi world, Carlebach unself-consciously continued to wish people a Gut Shabes and Gut Yontef like his forefathers did, instead of the more mainstream Shabbat Shalom and Shavua Tov. And when Carlebach spoke or sang Ashkenazi, no one laughed.

Although there may have been serious flaws in Carlebach’s character, he managed to single-handedly deepen the intensity of the Jewish religious experience for countless Jews throughout the world. Just as we Jews need to separate the strengths and the deep ethical flaws of our forefathers (King David, for example, had a soldier killed at the front just so that he could take his wife), so too we need to acknowlege the strengths and flaws of Shlomo Carlebach. Otherwise, by banning those melodies that have given so many Jews a deeper connection to their heritage, we’re only punishing ourselves.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO