Activists to Novominsk Rebbe: Support Victims, Not Predators

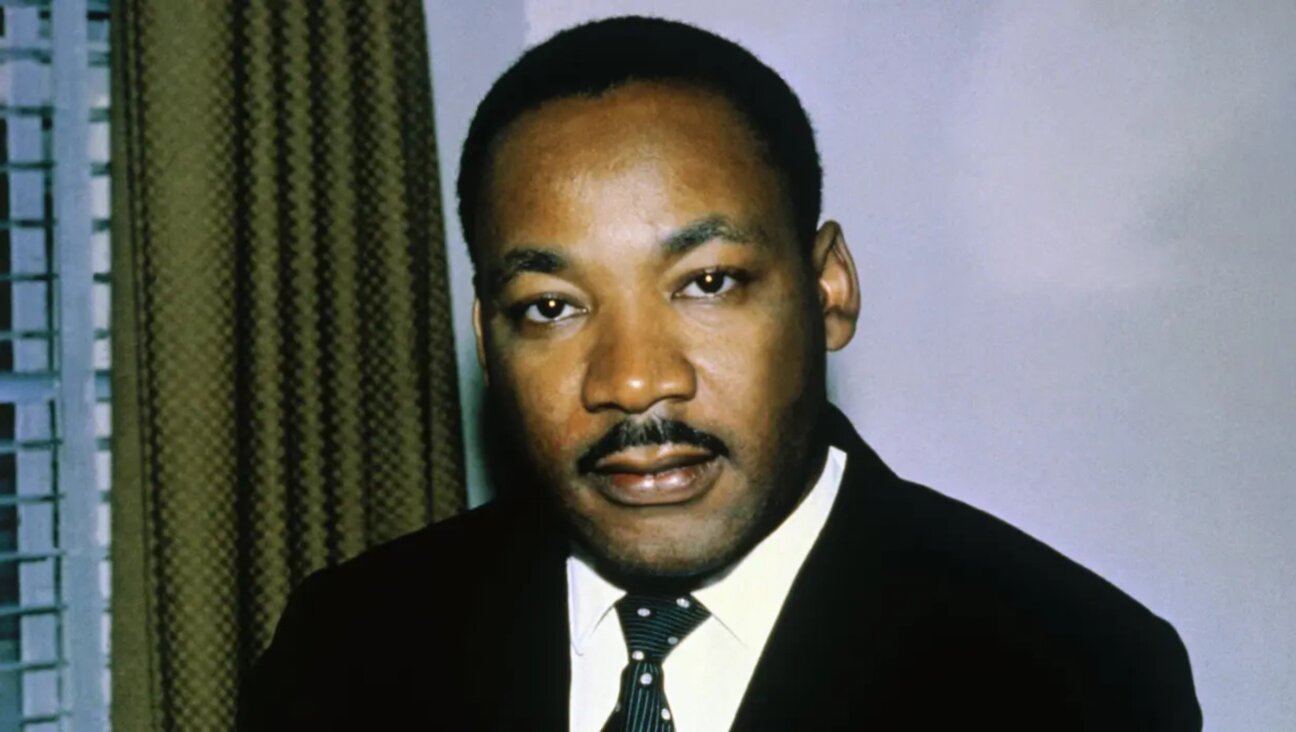

Image by Mo Gelber

This article originally appeared in the Yiddish Forverts.

The third child sexual abuse awareness protest in Brooklyn this year got off to a quiet start. That was actually good news for the dozen demonstrators in front of Borough Park’s Novominsk Yeshiva on this warm fall afternoon.

At a previous rally, elsewhere in Brooklyn, an ultra-Orthodox passerby had told demonstrators that God was offended by men and women protesting together and they were all going to die. Then he set a flyer on fire. The subject of child sexual abuse is so inflammatory that Asher Lovy, a seasoned activist in the movement for a Child Victims Act (CVA) in New York State, a survivor of child sexual abuse and the organizer of all three protests, now insists on a police presence at every protest demonstration.

Upon the arrival of an NYPD Community Affairs police car at the protest last month, Lovy marshaled his troops into action with an electronic bullhorn and the confidence, borne out, that the police were on hand to keep the peace. The likelihood of violence now reduced, Lovy led his allies against Rabbi Yaakov Perlow — the Novominsker rebbe and an opponent of the CVA — in a recitation of slogans at a Brooklyn corner thick with Hasidic schoolchildren, Sunday shoppers and curious onlookers.

“Protect victims, not rapists!” the protesters chanted.

Lovy bans the use of profanity at his demonstrations, but the slogans stung nevertheless.

“Hey Perlow, Zwiebel, Halacha has no SOL!” the protestors yelled, pointing to Rabbi Perlow and Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel, vice president of Agudath Israel, a U.S.-based Orthodox policy-setting organization, as defenders of New York State’s statute of limitations (SOL), which caps a victim’s right to file suit against his or her abuser by age twenty-three. Several demonstrators said they were on hand to support the CVA, legislation, currently stalled in the New York State Senate, that would allow victims to bring civil cases up until their fiftieth birthday and felony criminal cases until their twenty-eighth. It would also open a one-year window during which people whose cases have passed the statute of limitations could still file suit against their abusers and the institutions that protected them.

Another chant pointed to an apparent meeting of the minds between Catholic and Orthodox Jewish authorities, both of whom have lobbied the New York State Senate to keep the statute of limitations in place: “The Catholics and Agudah! United in Retzicha!”

Retzicha is the Hebrew and Yiddish word for murder, and suggests a link, increasingly given credence by mental health professionals, between child sexual abuse and a host of mental illnesses in later life, including suicide.

Yet another chant — “Abuse is retzicha, reporting’s not mesirah!” — targeted a centuries-old legal injunction against reporting the actions of a fellow Jew to non-Jewish authorities. Indeed, mesirah has deep roots in Jewish history. An eighteenth century case of mesirah in Wojslawice, Poland resulted in the massacre of the Jewish community by the local Catholic authorities.

“I’m afraid I have nothing to say about the ugly chants,” Agudah director of public affairs Rabbi Avi Shafran wrote to the Forverts in an email.

But by way of a 2011 statement he wrote for Agudah, Rabbi Shafran challenges Lovy’s allegations regarding mesirah: “Where there is raglayim la’davar (roughly, reason to believe) that a child has been abused or molested, the matter should be reported to the authorities.” The issue becomes complicated, however, when the “circumstances of the case do not rise to the threshold level of raglayim la’davar.” In those cases, Rabbi Shafran wrote, “the matter should not be reported to the authorities.”

“In many cases,” Rabbi Shafran adds, “there is some doubt about whether that threshhold has been reached, and in those cases, we counsel people to speak to halachic authorities with expertise in the area of child molestation.”

What constitutes “doubt” and “reason to believe” have long been a bone of contention between Agudah and supporters of the CVA.

“Many survivors and activists have sat with Agudah,” Lovy wrote in a June 2017 blog post. “Negotiated with them. Poured their hearts out to them. Appealed to the consciences they hoped Agudah had. Nothing worked. They’ve protested outside their offices, outside their annual dinners. It’s gotten us nowhere. Agudah remains stubborn in its policies.”

Samuel Heilman, a professor of sociology at Queens College, chair in Jewish Studies at The Graduate Center (CUNY) and a critic of Hasidic insularity, believes that a transparent discussion about child sexual abuse in Orthodox Jewish communities is less a matter of halachic debate than rabbinic power.

“If outsiders can be right in their judgments about the faults of the insiders — especially those in positions of moral authority — maybe they are not so wrong about everything else,” Heilman wrote in an email to the Forverts. “To believe that is to take a fatal step on a slippery slope towards the belief of plural life worlds, tolerating differences and thinking all the answers might not be in possession of the rabbis.”

A lapsed Orthodox eighteen-year-old protestor from Chicago echoed Heilman’s analysis. “Child sexual abuse is protected by the leadership because of the gendered nature of the leadership,” he said. “The leadership and the community mistrust people outside the community. I’m here to say that child sexual abuse is real and I support my friends who grew up Orthodox — and sexually abused.”

At the heart of the problem

According to its 2011 statement, Agudah’s ancillary concern is the financial trauma that schools and synagogues would suffer in the event of successful lawsuits brought against sexual predators and the institutions that tolerate them. As Rabbi Shafran wrote, “What Agudath Israel and Torah Umesorah [an Orthodox Jewish organization promoting Torah-based religious studies] must object to… is legislation that could literally destroy schools and houses of worship… Legislation that would do away with the statute of limitations completely, even if only for a one-year period, could subject schools and other vital institutions to ancient claims and capricious litigation, and place their existence in severe jeopardy.”

“They admit it,” Lovy says. “Child sexual abuse is so pervasive in this community that eliminating the SOL would financially bankrupt its religious institutions.”

Lovy says he is gratified to see support surface where least expected — evidence that individual response to child sexual abuse is not reliably submissive to rabbinic pressure:

“At our July protest in front of the Novominsker Shul, one guy stopped his van in the middle of the street, with his family seated inside, and yelled out, ‘The only answer is 911! If you’re molested call 911!’ He thanked us for what we were doing.”

Lovy recalls that at the June protest, a flower shop owner from Flatbush took some placards and posted them in her store window.

“Doing nothing would shame me”

As the afternoon wore on, Borough Park residents appeared to take the protest in stride. A small group of Novominsk yeshiva students peered out of the first-floor windows at the protestors, whose numbers eventually grew to twenty-five. Before long the high school-aged students stood together in a tight knot outside the yeshiva, finally venturing past the protestors without making eye contact. A younger klatch of black-hatted youths watched the demonstrators from their beachhead at Breadberry’s, a kosher grocery across the street.

One boy worked up the courage to grab a flyer, a double-sided sheet produced by Zaakah (Shout), a victims’ rights group whose guerrilla tactics earlier this year included a protest outside Rabbi Zwiebel’s family home. A seemingly exasperated Hasid associated with the Novominsk Yeshiva paced up and down the sidewalk, but did not confront Lovy or the other protestors.

By five o’clock when the protest ended, neither Lovy’s group nor the administrators at Novominsk had spoken a single word to each other: A grassroots Jewish group and an Orthodox Jewish institution could not or would not find common ground.

One married man in his thirties, who had struggled to describe his reason for showing up at a demonstration on a beautiful Sunday afternoon, expressed his mixed feelings about the day’s event.

“Being here terrifies me,” he said. “But doing nothing would shame me.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO