Architects and Artists Building the Jewish State

Boris and Bezalel Boris Schatz sits at the entrance of the Bezalel Art School, circa 1920. Image by wiki commons

The half-century before the declaration of Israel’s statehood was a time of wild artistic ferment. Some of the nuances of the feverish creativity in the realm of architecture are described by two studies from Ashgate Publishing, “Constructing a Sense of Place: Architecture and the Zionist Discourse” edited by Haim Yacobi and “Architecture and Utopia. The Israeli Experiment” by Michael and Bracha Chyutin.

Further confirmation of the rapid innovation, should it be needed, is available in a 2011 work so far only available in Hebrew, “Architecture in Palestine During the British Mandate, 1917-1948”, by Ada Karmi-Melamede and Dan Price, published by the Tel-Aviv Museum of Art. And by another title out in late 2011 from GTA Verlag, “Europe in Palestine: Architects of the Zionist project 1902-1923.” The site-specific innovations occurred from crossing artistic and stylistics genres for inspiration, even looking to unlikely and highly un-biblical sources.

Written by historian Ita Heinze-Greenberg, who has previously published volumes about the German Jewish modernist architect Erich Mendelsohn, “Europe in Palestine” has a wide scope, including the way visual artists aimed at evolving a new synthesis in the Holy Land. This includes the art nouveau prints of Ephraim Moses Lilien, much influenced by the turn-of-the-century British decadent artist Aubrey Beardsley.

Heinze-Greenberg reproduces a Beardsleyesque 1902 illustration by Lilien to a poem by the Yiddish author Morris Rosenfeld in which among a group of male nudes, 19th century versions of erotic Greek vase paintings, appears an unmistakable portrait of Theodor Herzl, his modesty preserved by a flower which blooms in the image’s foreground as fig-leaf.

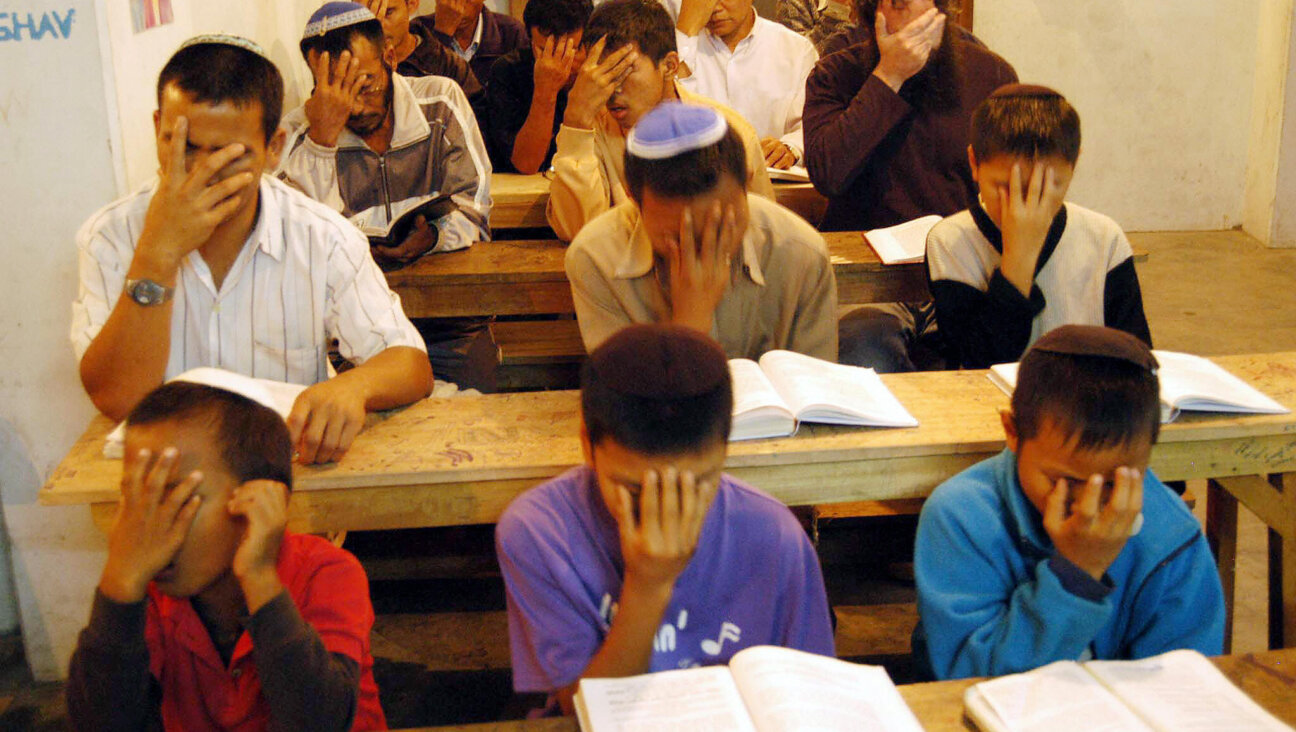

The Galician-born Lilien, sometimes called the “first Zionist artist,” blended ancient Greek and modernist elements to arrive at a new vocabulary. Others, such as the Lithuanian Jewish artist and sculptor Boris Schatz, who in 1906 founded Jerusalem’s Bezalel School, saw Zionism as a chance to blend his own Jewish identity and creative urges. Blending Eastern and Western motifs, Schatz’s approach earned the patronizing scorn of C. R. Ashbee, then-civic adviser to the British Mandate of Palestine and chairman of the Pro-Jerusalem Society. In a later memoir, Ashbee was condescending about the “happy, breezy, if somewhat pathetic personality of old Professor Schatz” and dismissed Bezalel as a “brilliant failure” in its attempt to derive a “Jewish style, something that should signify the living Zionism in Palestine, was possible.”

Fortunately others were less pessimistic, including multi-talented architect Alexander Baerwald, best remembered for his buildings in Haifa, who was also a gifted cellist who performed in a Berlin string quartet for which Albert Einstein was the second violinist. The Frankfurt-born architect Richard Kauffmann played second fiddle to no one in his ambitious town planning, as Heinze-Greenberg’s narrative also compellingly explains.

Watch a video about Boris Schatz and the Bezalel School.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO