When Yiddish Came to North Korea

On September 4, 1965, Lin Jaldati stepped onto a stage in Pyongyang, North Korea and quite possibly became the first person in Communist North Korea to sing in Yiddish. As I will discuss in a July 13 talk at the Yiddish Book Center’s Paper Bridge Summer Arts Festival in Amherst, Mass., Jaldati and her husband, Eberhard Rebling, became the voices of leftist Yiddish culture throughout the Communist world at the height of the Cold War.

Jaldati’s story begins in Amsterdam, Holland, where she was born in 1912 and raised in a Jewish family with Dutch as her native language. A member of labor Zionist circles, she trained as a dancer and performer and learned Yiddish in order to participate in the Jewish immigrants’ Yiddish culture club.

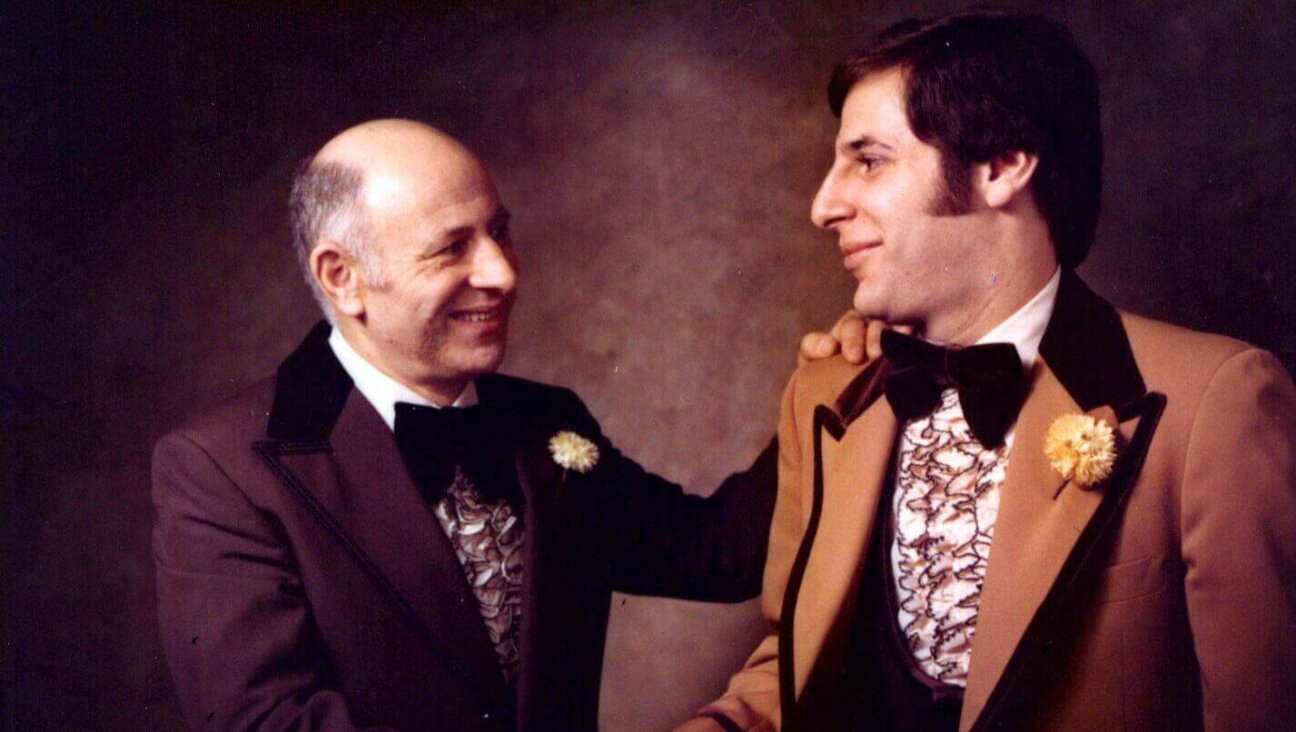

It was Eberhard Rebling, a German socialist, musicologist and pianist, who encouraged Jaldati to make Yiddish her life’s work. He arrived in Holland in 1935 as part of a wave of German émigrés driven out of Germany by Nazism. In 1936 he met and fell in love with Jaldati. The same year she gave her first Yiddish performance at a large rally in Amsterdam protesting the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and the couple stayed together until her death in 1988.

From that moment in Amsterdam the Jaldati-Rebling team became one of the most visible voices of Yiddish culture in Europe. Against all odds, the two lived through the Nazi occupation of Holland. She survived Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen and was one of the last people to see Anne Frank alive. He ignored his German draft orders and went underground, was hunted by Dutch Fascist police and, at one point, was arrested for draft violation. In May 1945 the two reunited — she a physically, but not spiritually, broken woman, he one of the leading Communists in post-war Holland.

In the late 1940s, Rebling, who was then the music editor of the Dutch Communist paper, De Waarheid, was invited to the newly established German Democratic Republic to take an important position in the new state’s music establishment. Jaldati was also invited to use her voice to “clear out the rubble in people’s heads” after 12 years of Nazism. In 1952, they took the plunge with their two daughters and moved from Amsterdam to East Berlin.

After struggling initially with her lack of German and an unclear professional position, Jaldati quickly became a recognized voice in East German culture, performing regularly on the radio. But unlike Rebling, for whom the move to Berlin was a re-migration along with many other German socialists, Jaldati was in a strange land, and not just any land, but the birthplace of the Holocaust. On more than one occasion, she was confronted with the question any Jew in post-war Germany faced in those years: “How can a Jew live in the country of Hitler?”

Since homecoming could not be her answer, Jaldati always replied that she lived in the part of Germany that had overcome its Nazi past by embracing socialism, unlike the neighbor to the West, which was still run by unreconstructed Nazis. Clearly, she had her GDR ambassadorial role down, and over time she served as an important cultural ambassador for this “bulwark of socialism” in Europe. Reading through her diaries and letters it is clear that although she may have been ambivalent about moving to East Germany and leaving her home, she was not ambivalent about defending the GDR to skeptical audiences.

In the 1960s, she and Rebling took on the larger role of bringing European anti-Fascist music to the emerging global Communist empire. After a late 1950s visit to Moscow to pay homage to the center of the Communist world, the two toured Asia, bringing Beethoven, Bertold Brecht, and Yiddish music wherever they went. Their 1965 tour took them to China, where in Shanghai, according to Jaldati’s diary, they performed to a concert hall of 1500 people, just a year before Mao’s Cultural Revolution ended such European-Chinese exchanges. On the same trip, they visited Pyongyang, performing the same repertoire for North Koreans of all ages.

On other trips, they toured Indonesia, Thailand and India, and in 1979, they performed in Kampuchea, just after Vietnam ended Pol Pot’s bloodbath that killed 20% of the Cambodian population. It was so humid in Southeast Asia that Rebling couldn’t play his piano, so they sang a capella.

As I immerse myself in this story, I sometimes pause in shock, thinking how strange it was that a Dutch Jewish Holocaust-surviving Yiddish songstress would sing Mordechai Gebirtig’s “S’brent” and the classic Vilna Ghetto song, “Zog nit keyn mol” a capella to a group of Indonesian peasants in mountaintop villages. But sing she did, on the Yiddish tour heard ‘round the world.

Listen to Lin Jaldati sing ‘In Kamf’:

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO