We can be thankful this year — and Jewish wisdom can help

Yes, we are living in a time of uncertainty and dread, but Jews have some experience with that.

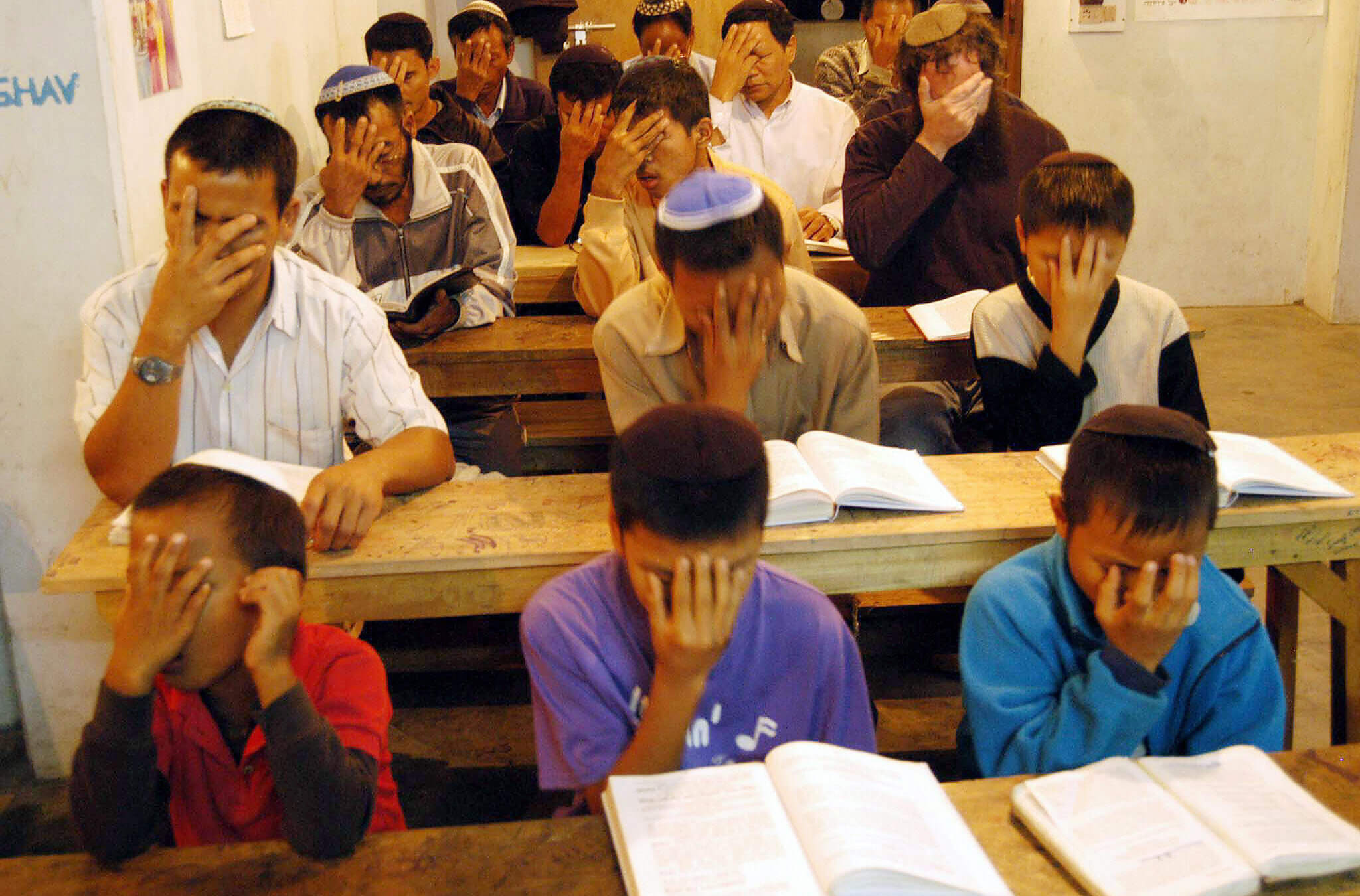

Jews place their hands to their faces in prayer. Photo by Getty Images

I am not feeling especially thankful this year.

Like around three-quarters of American Jews, I am still reeling from the consequences of the election — not the outcome, exactly, but the dread of what is to come. I wish we could just jump to Jan. 20 already, and see how much of Trump’s rhetoric will become reality. At least then we could be fighting against something real, rather than phantoms.

But no, like the writer in Stephen King’s Misery, we just have to lay here and wait until Kathy Bates hits our leg with a sledgehammer. Again.

It’s not only Trump, of course — it’s ethnic cleansing in Gaza, it’s the climate crisis, it’s online trolls, it’s health struggles at home. I know, of course, there are many things I should be grateful for. But I also know I don’t want to celebrate anything, least of all ‘Thanksgiving.’

But I am going to do it anyway.

My sister hosts Thanksgiving every year, and I’m not going to spoil the holiday for my family or for my seven-year-old daughter, who is blissfully unaware of the looming disasters in our country. It’s not about me.

So what to do? How to make this Thanksgiving at least somewhat sincere?

In reflecting on this, I’m aware of an interesting convergence between Jewish religious practice and the insights of positive psychology. Namely: that cultivating gratitude is a thing you ought to do precisely when you don’t want to do it.

Observant Jews pray three times a day, even if they’re busy, distracted, angry or upset. Even if it’s a hassle to find a minyan to pray with. Even if they don’t want to pray in the least.

Why? On a mythic-legal level, because it’s part of the system of commandments. But on a functional level, because prayer is a technology of state-change. If done correctly, and even if done half-heartedly, it replaces what’s in your mind with other stuff, including important stuff like peace, coexistence and holiness. It shifts your consciousness from kvetching (even justified kvetching) to a wider perspective.

Sure, to pray when your heart is glad is a joyous thing. But to pray when your heart is broken offers the possibility of healing.

Likewise, a number of psychological studies have shown that cultivating gratitude, even without the desire to do so, can improve all happiness. It’s not that joyful people are grateful — it’s that grateful people are joyful. See the difference? Gratitude isn’t a baseline emotional setting; it’s something that results from intentional practice. Cultivating gratitude is like building muscles at the gym. The love you take is equal to the love you make, sang Rabbi McCartney.

I admit, right now feels like one of those times that I drag myself to the gym, resentful of my own self-discipline. But that’s fine. I can schlep myself to the gym, and I can schlep myself to a place of hakarat hatov — recognizing the good that is in my life, even amid all the dreck.

And, let’s face it, Jewish history is filled with dreck. My ancestors found the inner resources to dance with the Torah in the middle of Nazi ghettos, during the Spanish Inquisition, in the trenches of Israeli wars, in appalling poverty, in times of despotic rulers who hated the Jews, and in a thousand other circumstances far, far worse than my own. Surely, if they can muster the ability to feel joy, I can too, right?

One of the great expressions of Jewish joy is found in Ashkenazic musical traditions like klezmer and the niggun. If you’re not familiar with them, these musical forms can be, well, a little unusual. I have a little joke with my partner, who grew up Unitarian-Universalist, that in UU worship services, everything, even sad songs, is in a major key. But in Jewish services, even the joyful parts are in minor. Oy.. we’re so thankful to you, God… oy, oy, oy.

There is a deep wisdom in this juxtaposition – one that stands in stark opposition to the “toxic positivity” popular on the Internet today (and, for that matter, the maddening songs of the Christmas season). Our ability to find joy is not predicated on the denial of reality. We know that there is much that is broken in the world. But we find a way to sing, and dance, nonetheless.

Jews are hardly the only people with such traditions. Some of the most beautiful music in American history was created by Black musicians living under Jim Crow and even slavery. From segregated dance halls, churches, and jazz bars came some of the most transcendent, uplifting sounds that human beings have ever created. The heartbreak of the blues, the yearning of gospel and soul music, and the intensity of hip-hop were all born of profound suffering and injustice.

So it’s not just Jews. On the contrary, seeing these resonances reminds me of our solidarity with other groups that have experienced oppression — a solidarity soon to be tested. It reminds me who “my people” are — not only the ones with whom I share a background, culture and history, but all those who yearn, who struggle, and who care about the wellbeing of others.

But it is also Jews. Even setting aside the seemingly eternal scourge of antisemitism, Jewish history and literature are replete with stories of a world gone mad, a world in which powerful, corrupt men often rule the day. It’s a world of pharaohs, of unrighteous kings of Israel, of occupiers from Greece and Syria and Rome. And until relatively recently, it was a world without modern medicine, vaccines and scientific understandings of disease and health. (We may soon be returning to that world as well.)

This is the world that my ancestors lived in, the ones who birthed hymns like Yedid Nefesh and Lecha Dodi, gave us joyous holidays and delicious foods, and even posited the existence of a God who is good and who loves us. How could people who suffered so much have created such beauty?

Perhaps that question — and whatever answers may lie buried in the human heart — is where I’ll turn my attention this Thanksgiving.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO