I’m a Mexican Jew. I wish Claudia Sheinbaum would embrace the complexity of our shared heritage

Sheinbaum, who will be the first woman and first Jew to serve as Mexico’s president, has rarely addressed her Jewishness in public

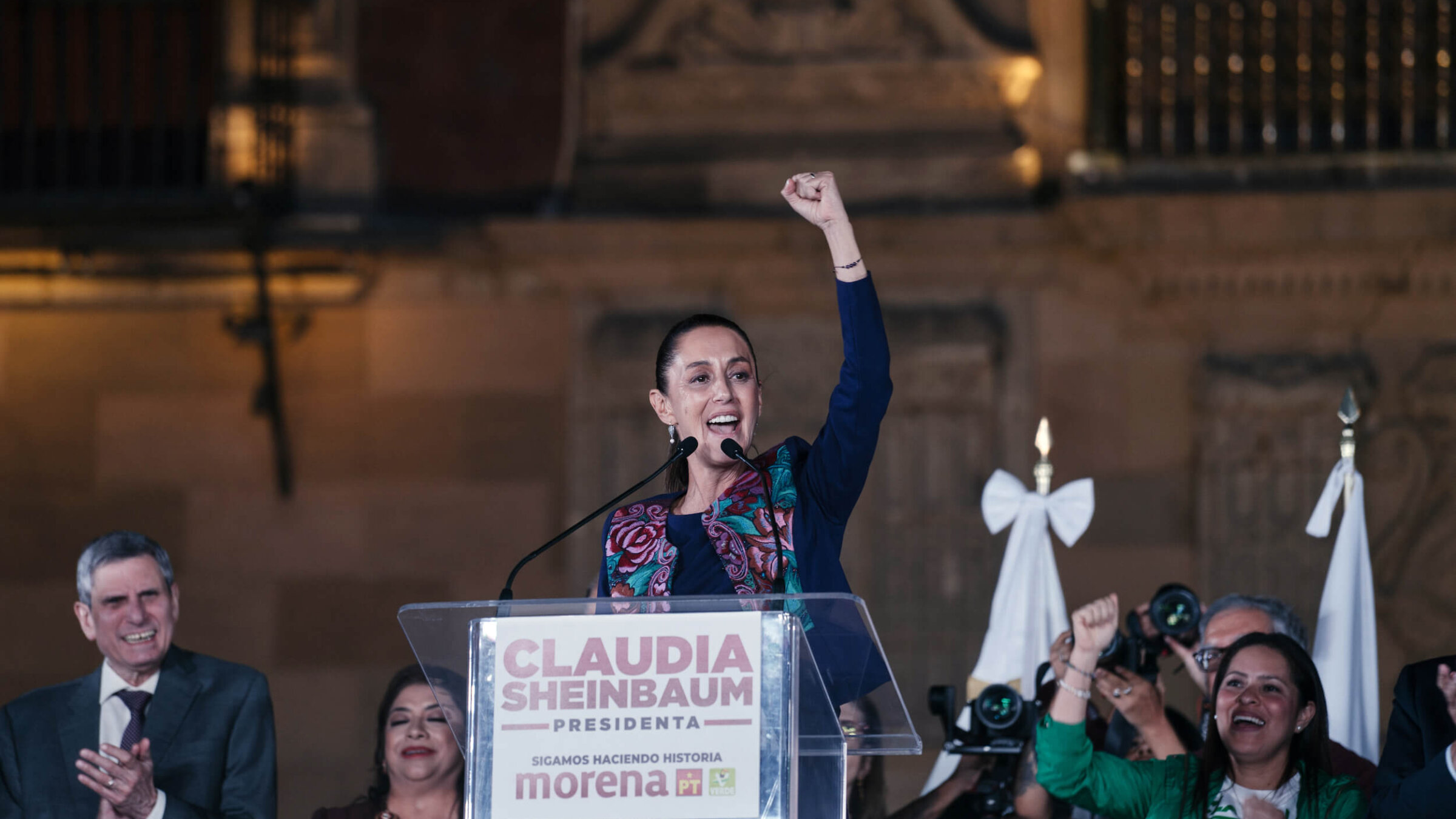

Claudia Sheinbaum gives a victory speech after winning Mexico’s presidential election. Photo by Luis Antonio Rojas/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Every year on Rosh Hashanah, my family serves gefilte fish a la Veracruzana, a Mexican twist on the traditional Jewish dish in which delicate fish patties are served warm in a spicy tomato sauce. Named after the port of Veracruz, the main entry for 20th-century immigrants to Mexico, the fusion honors my great-grandparents who fled Europe for Mexico in the 1920s. Since then, my mother’s side of the family has been a part of a historically vibrant Jewish community in Mexico City, still home to 59,000 Jews today.

As proud as I am of my dual cultural heritage, growing up in New York City, I often found it difficult to express my Mexican identity. I don’t look the way many Americans expect the average Mexican to look. I don’t come from a Catholic family, the nation’s most common religious background. Neither does Claudia Sheinbaum, Mexico’s newly elected next president, a former mayor of Mexico City and climate scientist who hails from a Jewish family in Mexico City. Her paternal grandparents arrived in Mexico at the same time as my great-grandparents, fleeing persecution in Lithuania during the 1920s. Her maternal grandparents escaped the Nazis in Bulgaria.

In theory, the first-ever election of a Mexican Jewish woman to the country’s highest political post should reaffirm the validity of my own dual identity as a Mexican Jew. In practice, it’s left me wishing that Sheinbaum would seize the opportunity to stop downplaying her Judaism, and start embracing it. Her historic victory presents her with an opportunity to meet challenges to her dual identity — 100% Mexican, 100% Jewish — with a sense of pride that celebrates the unique fusion of the two.

Sheinbaum has frequently de-emphasized her Jewishness. In her victory speech Sunday night, she emphasized the significance of her becoming Mexico’s first female president, but made no acknowledgement that she will also be the country’s first Jewish president. While she has privately discussed her culturally Jewish upbringing, Sheinbaum rarely makes public mention of it, even as opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez took to X, formerly Twitter, last September to wish the Jewish community a happy new year and a “blessed” Yom Kippur.

Not only does Sheinbaum refrain from discussing her Judaism, she actively downplays it, possibly to protect her image and to appeal to the overwhelming majority of Catholic voters. On the campaign trail, she gained attention for wearing a Catholic rosary necklace and skirts decorated with an image of the Virgin Guadalupe.

I cannot speak to Sheinbaum’s personal experience, but I understand why she might be reluctant to publicly embrace her Jewish heritage. Too often, I’ve found myself excluded or unwelcome in spaces meant to celebrate Hispanic culture, in part because my Mexican-ness has been challenged and invalidated by those who struggle with the concept of dual cultural identities. In my public New York City high school a few years ago, a classmate asked me if I was a “real Mexican” or “the colonizer type of Mexican.”

For those like me, Sheinbaum’s election as a Jewish leader in a nation of nearly 100 million Catholics should be inspiring, an opportunity to display the rich history of Mexican Jewry and the diversity of the Jewish diaspora more broadly. Instead, her tortured cultural balancing act feels all too familiar.

Legitimate political concerns may inform that act. Sheinbaum has been the target of hypernationalist, antisemitic prejudice, including online birther conspiracy theories alleging that she was born in Bulgaria. Former president Vicente Fox has referred to her as a “Bulgarian Jew” and “Jewish and foreign” in separate posts on X.

Sheinbaum has countered such online attacks, however, with nationalist rhetoric of her own. In one since-deleted post on X containing a photo of her birth certificate, she wrote “I’m more Mexican than mole” — referring to the popular Mexican sauce. In another, she declared she is “100% Mexican.” To me, this defensiveness suggests not just pride in being Mexican, but also a deep discomfort with her Jewish background. Perhaps not surprisingly, the Mexican Jewish community in this election mostly indicated support for Gálvez, rather than Sheinbaum, who has never integrated herself with the tightly knit Jewish community of Mexico City.

Sheinbaum’s hesitation around her Judaism feels particularly charged, to me, at a time where Jews across the world are grappling with rising rates of global antisemitism. So many of us have spent recent months feeling in some way alienated from our non-Jewish communities, or, at the very least, grappling with the question of how our Jewish identity fits into our secular lives.

On my own college campus, I watched as my Jewish classmates were deliberately ignored by the campus directors of the Yale Women’s Center after reaching out to discuss how the organization could better represent Jewish women’s voices on campus. I heard terror from my Jewish friends at Cornell University after a student posted anonymous online messages threatening to shoot Jewish students in the kosher dining hall.

The truth is that whether or not Sheinbaum feels strongly connected to Judaism, it will always be connected to her. That’s certainly the sentiment among her critics, some of whom have already racked up millions of views for posts on X that use her Judaism to invalidate her leadership. That’s deeply sobering. But the extent to which her heritage is part of her profile — regardless of her own approach to it — also means that she has a chance to make many of us feel that much more seen by celebrating her Jewishness.

Taking such a step would be deeply meaningful to Mexican society at large. Indigenous, Black and LGTBQ+ Mexicans, among others — all of whom have enriched the nation’s cultural tapestry, yet have been historically marginalized — should feel empowered to see diverse identities celebrated and embraced in the public sphere.

Ultimately, that empowerment will be the key to fostering a truly thriving society. As Sheinbaum prepares to tackle some of Mexico’s most pressing social issues, including a femicide crisis amid a national culture of machismo and stigma surrounding LGBTQ+ rights and abortion in a historically conservative Catholic country, she should strive to showcase the multiple identities and ancestries that comprise Mexican society. She can start by capitalizing on the opportunity right in front of her.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO