How do you teach an incarcerated student with a swastika tattoo?

As the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, one particular student posed my greatest challenge

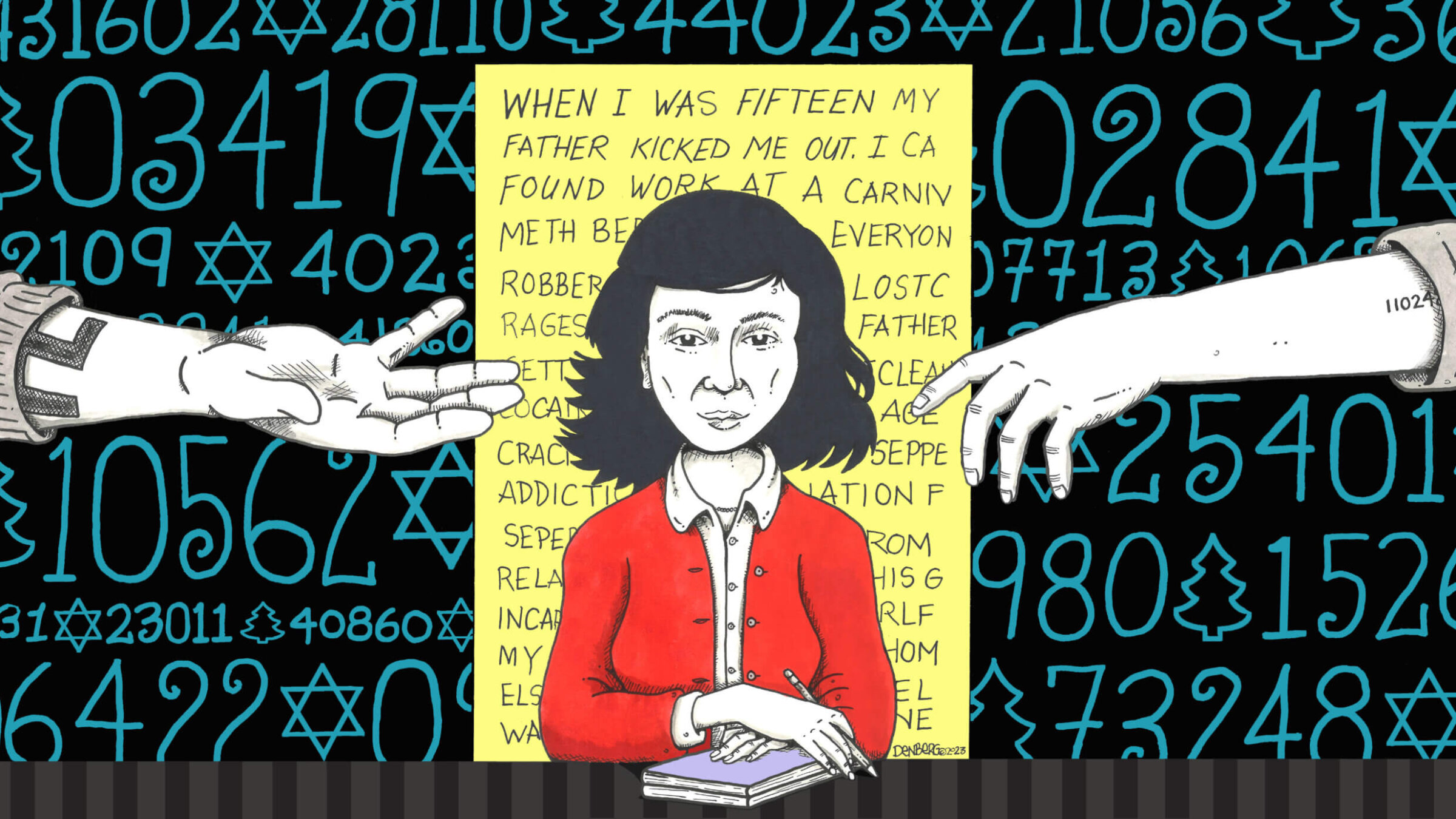

Illustration by DenBerg

I panicked when C, one of my students at the correctional facility, rolled up his sleeves to display a large black swastika tattooed on his right forearm. (His full name is being withheld due to safety concerns.) He was sitting next to me at the conference table in the small room where we met for my weekly storytelling program: 12 men and I squeezed on plastic chairs with security cameras pointing at us.

This was the third session of the six-week program at this rural county jail in New Hampshire, and I hadn’t noticed the tattoo before.

Years of teaching in correctional facilities have trained me not to get easily flustered. But as the child of a Holocaust survivor, I felt a shiver of fear when my eye fell upon the swastika, filled in with black ink and framed by a black line to add volume. It was so large it almost wrapped around his arm.

In my mind, I backtracked through everything I had revealed in the previous sessions. Had I said that I’m Jewish? Had I given my last name? Had I mentioned in which town I live? Could he pass on my information to his white-supremacist buddies? I hesitated. I didn’t know what to do. But then I decided to fall back on the philosophy I have adopted: to make myself vulnerable.

I’ve been teaching at correctional facilities for almost 10 years, and it is always tense. The men tend to be suspicious of an outsider like me who hasn’t lived their experiences. They see right through me when I present myself as some kind of expert offering life lessons. My best classes happen when I let go of my role as a teacher, suspend my judgment and just try to connect at a human level. I intentionally share my most intimate stories with these men, knowing I can’t expect them to open up unless I do so myself.

Most of my students are the product of generational poverty, abuse, neglect and addiction. They have learned to act tough and pretend not to care.

Many have watched clients and friends die of overdoses, have beaten their girlfriends and wives, have robbed convenience stores, or have crashed cars in police chases because they had given up on life.

With me, however, they are sober and full of hope. Participation in the workshop gives them good-behavior credit towards parole, and they are eager to be released.

Their hopes and goals tend to be heartbreakingly modest: get clean, find a job, be a good parent. I owe it to them to believe change is possible. So I let go of judgment and try not to be shocked when they recount stories about violence and recklessness that would scare me in any other situation. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from teaching at correctional facilities, it’s that good and evil are complicated and that people never just are what they seem to be.

Eventually, the stories they tell that matter most are the ones about simple moments in life: about the birth of a child, memories of a trip to an amusement park, going hunting with a father, or finding love.

Without acknowledging C’s tattoo, I took my turn to tell a story about growing up Jewish in Amsterdam. When I was 8, I won the class Christmas tree in a lottery on the last day of school before winter vacation. But when I told my parents that I had won, they reminded me that as Jews we didn’t celebrate Christmas and made me give away the tree to another child.

I resented being different and just wanted a Christmas tree like everyone else. We were completely secular. We didn’t even believe in a God who would disapprove of us having a Christmas tree. What most tied us to Judaism was the Holocaust, as the Nazis had murdered my father’s immediate family. I knew about the terrible things that happened to Jews, so I didn’t understand why we didn’t just erase our Jewish identity and try to blend in.

As a child, I didn’t understand that getting a Christmas tree wasn’t enough to stop being Jewish. Before the war, my father and his sister had been secular and thought they could shed their Judaism. But when Hitler occupied the Netherlands in 1940, they were forced to wear yellow stars. My father and aunt were part of the resistance and went into hiding, but in the spring of 1943, my aunt and grandmother were arrested and transported to the Sobibor death camp in Poland.

My father didn’t talk much about the Holocaust. Long after his death, I learned that he had considered naming me Bernardine after his sister, who had been his best friend, but refrained from doing so because Ashkenazi Jews don’t name their children after living relatives. Even though decades had passed, he didn’t want to tempt fate if his sister was still alive somewhere in the world. Instead, he named me Judith (“Jewish woman” in Hebrew), in acknowledgement of the many Jewish people who have been murdered.

I, in turn, have named my own children after my father and his sister. I feel an obligation to honor my Jewish ancestors who struggled to maintain their tradition throughout the centuries. So, even though we’re not religious, my children did their b’nei mitzvah, and we have never had a Christmas tree.

The class was silent when I ended my story. “Wow,” someone said. “That’s heavy.” Others nodded. I didn’t dare to look at C on my left, even though my story had been intended for him.

The next week, C gave me a yellow notepad filled with dense, angular pencil scribblings. He told me it was his autobiography and asked if I could read it and tell him what I thought. In 30 pages of rushed, phonetically spelled narrative he described how his father had kicked him out when he was 15 and how he found work at a traveling carnival that crisscrossed New England. He had started taking cocaine and meth because the older guys around him were using, and he became a father at the age of 17.

He wrote about his addiction, robberies, incarceration, the separation from his girlfriend, the loss of custody of his children, his jealous rages, his attempts at getting clean, relapse and homelessness.

I waited for an explanation of the swastika, but the story ended mid-sentence in an account of him trying to buy crack cocaine at a New York City street corner. It never mentioned his tattoo or his encounter with neo-Nazi ideology.

At the end of our last session, C shook my hand — the swastika again hidden under his sleeve — and thanked me for the workshop. He even asked me to write him a personal dedication in the book he had received for participating in the storytelling program. Neither of us brought up the tattoo.

Sharing his autobiography may have been C’s way of telling me that the swastika was just a footnote in his own story, not even worth recounting. That it meant more to me than it meant to him. Even if the tattoo had been the expression of a deliberate ideology of hate that he may have subscribed to at one point in time, what could he say about it to me now?

In the end, symbols mean nothing beyond the stories we tell.

To contact the author, email [email protected].

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO