The underground abortion my mother had, and the one she didn’t

‘To pay tribute to my father, I got a foster-care license and fostered seven children over the better part of a decade. I saw firsthand what happens to unplanned babies born to people who should not be parents.’

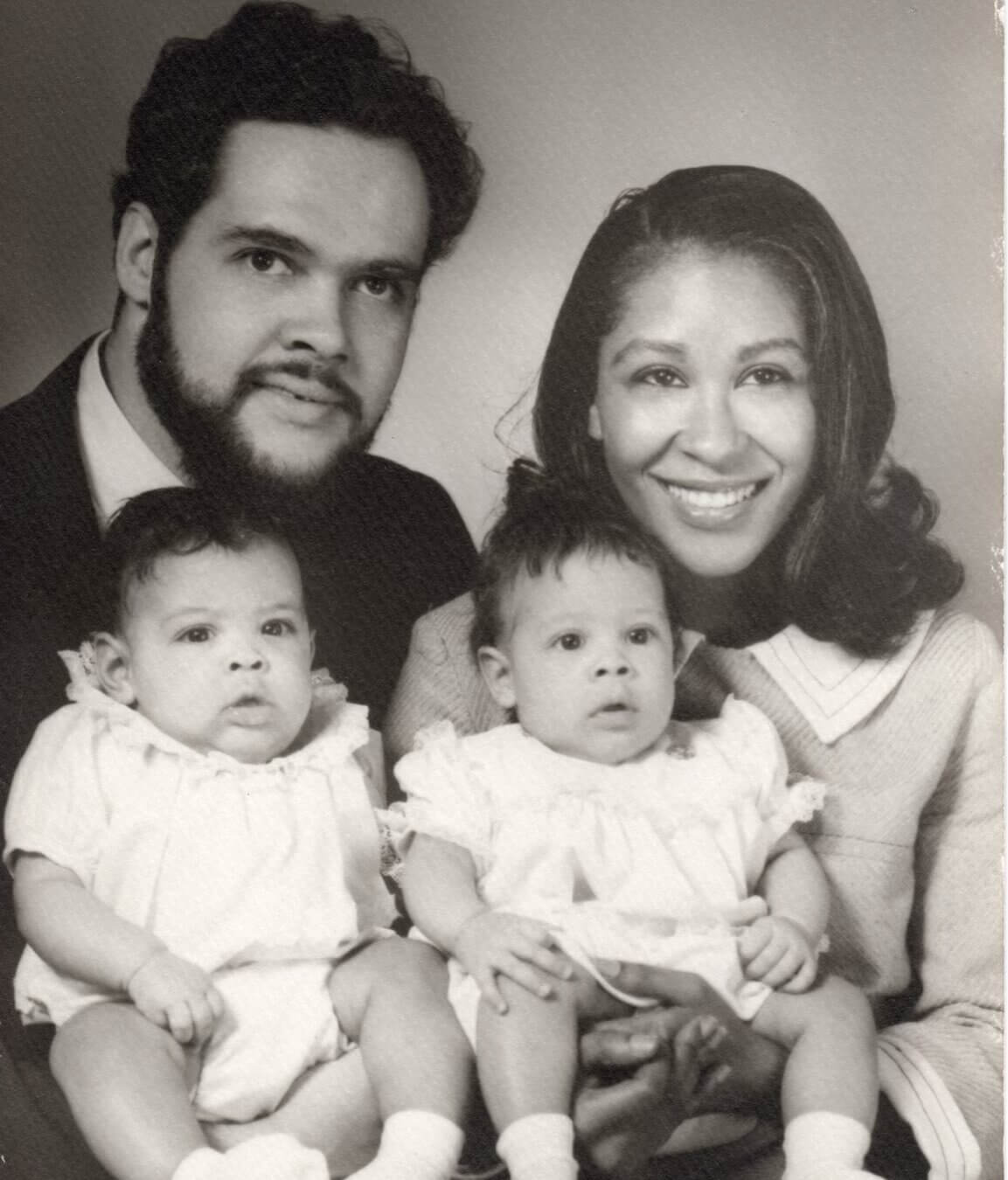

The Edelhart family in 1967: Arthur and Harriett, with twins Courtenay, left, and Ashley. Courtesy of Courtenay Edelhart

When my 84-year-old mother found out that the U.S. Supreme Court had overturned Roe v. Wade on Friday, she sighed heavily. “It won’t stop anyone,” she said. “People are going to die.”

She would know.

Years before I was born, my then-college student mother turned down a marriage proposal. Her mother and stepfather told her the whole point of college was to land a man—this was the 1950s—and if she was going to be turning down marriage proposals, they weren’t paying for her education anymore.

My mother had to drop out for a while to save money and apply for loans, but eventually she enrolled in a less expensive university and completed her education. With one hitch along the way: She unintentionally got pregnant.

My mother was unmarried. Her very religious Black and Christian parents would have lost their minds. And she hadn’t worked so hard to get back in school only to drop out again. So she turned to an underground abortion network that helped her induce a miscarriage with mysterious pills. The person she got them from wasn’t a doctor. She had no idea what was in the pills. She took them anyway. She was desperate.

More than a decade later, my mother became pregnant a second time, also by mistake because in the 1960s, it was hard for single women to get contraception. Plus, she had dated with a false sense of security, assuming that illegal abortion back in college had rendered her infertile. Her boyfriend was a decent guy, but when she met him he was in the middle of a messy divorce, and this new development would complicate it even further. Also, he grew up poor and was white and Jewish. Well, Jewish on paper, at least. He wasn’t religious in the slightest, but that nuance would mean nothing to my mother’s devoutly Christian, upper middle-class parents. Merely dating this man was scandalous enough. At the time, interracial marriage was illegal in 16 states. A biracial out of wedlock baby with a man who was technically still married was out of the question.

My mother told her boyfriend she wanted an abortion. After some discreet research, they tapped that underground network again. Had an appointment scheduled and everything. But at the last minute, my father talked my mother out of it. Not because he wanted me. It was because, first, he loved my mother and was afraid she could die if the procedure was botched. Secondly, abortion was against the law. If they got caught, they could get arrested.

Just their luck, it was twins. My parents got married after my father’s divorce finalized. But their marriage, too, would fail. They divorced when my sister and I were 13 years old.

My mother says she has no regrets about having her twins. Things were different than the first time she was pregnant. She had her college degree and a good job. She actually loved my father. Sure, her parents— and society — weren’t keen on it at the time. But the tides were changing. The Voting Rights Act had passed in 1965. Months after my sister and I were born in 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court voted unanimously to invalidate anti-miscegenation laws. The second time my mother was faced with an unwanted pregnancy, she felt more hopeful. That first time, however, would have been devastating.

I grew up hearing this story. I’ve been aware of it all my life. My mother wanted to make sure her daughters knew and appreciated the history. That we’d be passionate pro-choice feminists who would fight to make sure no one else had to endure the dreadful risk she’d illicitly taken once, almost twice.

I also grew up hearing my father’s horror stories about spending part of his childhood in foster care. Not because his mother and absent father were abusive, but because there was no safety net for my grandmother after her deadbeat ex left her with two children and a third on the way. She and her kids were quite literally starving. My father wanted his daughters to empathize with children who were hungry, neglected and abused. He devoted his life to those kids, spending his entire career as a social worker with Child Protective Services. That’s where he met my mother. She was a social worker, too. They wanted to repair the world.

To pay tribute to my father, I got a foster-care license as an adult and fostered seven children over the better part of a decade. I saw firsthand what happens to unplanned babies born to people who should not be parents. I heard the agonized cries of a drug-addicted newborn. I saw the terrified trauma of a toddler who’d been beaten and molested. I heard the wrenching sobs of a tween who had bounced around foster homes. I fought for the life of a suicidal teen.

When I tried like hell to get help for those children, most of the time I was told there was no public money for the services they needed. And few potential adoptive parents were willing to take them on. Nobody wanted them. Nobody cared.

I’ll keep fighting because both of my parents got their wish. I am a passionate supporter of a woman’s right to autonomy over her own body. I am also a passionate supporter of children. The two positions are not mutually exclusive.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO