Shocked by Russian war crimes? My father never forgot them

What Russians are doing to Ukrainians echoes what Soviet soldiers did to concentration camp survivors

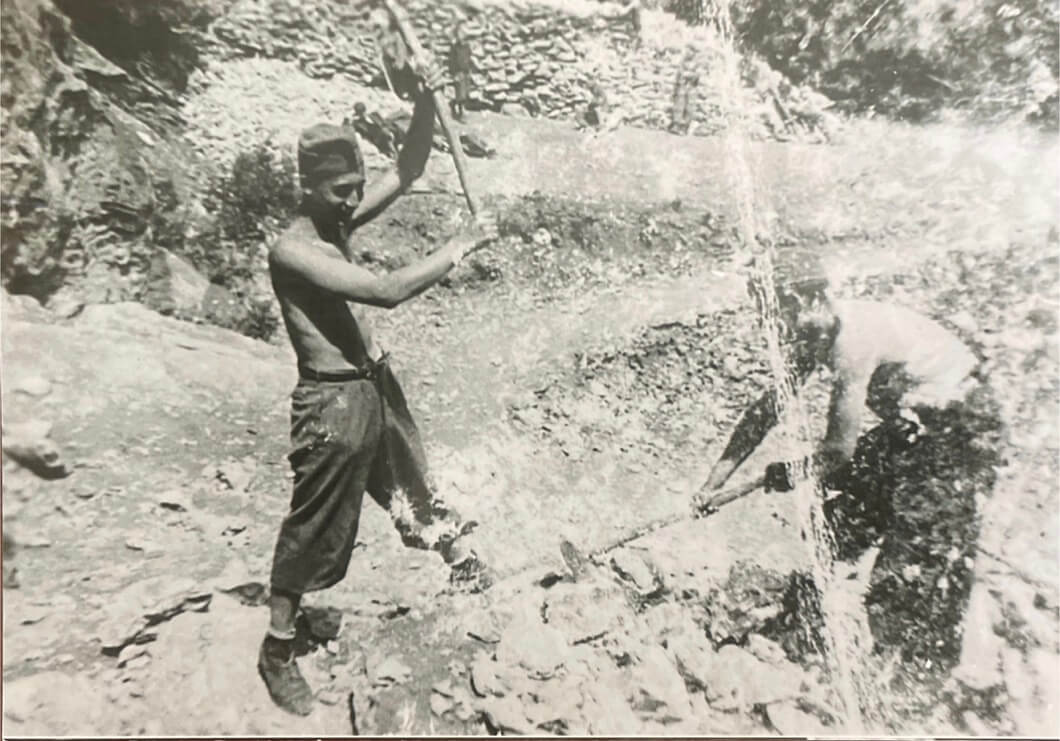

The author’s father, Cantor Andre Winkler, in the summer of 1944 digging petroleum tunnels while in forced labor camp. Courtesy of Janine Winkler

The war crimes Russian President Vladimir Putin, his generals and his army are committing against Ukrainians —raping, torturing and murdering civilians, leaving cities and towns in rubble — are shocking, but to Holocaust survivors and their descendents, they are far from surprising.

Though I was at first transfixed to the television at images of the atrocities, I now turn away. The “second generation” trauma that many children of Holocaust survivors like myself experience has washed over me like dirty water. That’s not only because the Russian war crimes remind me of Nazi atrocities, but also of Soviet ones.

The comparisons Nazi atrocities are all too obvious. But the shocking, brutal ways Russian soldiers treated Jewish survivors is rarely discussed. Their trauma was met with empathy and care by their American liberators, while the Russian soldiers reacted very differently.

As a so-called second generation child of a survivor the images of Russian tanks rumbling down country roads bring back to me the stories of my late father Cantor Andre Winkler’s interactions with this so-called “liberating army.” By some method of intergenerational transference, those stories have entered my psyche.

In 1944, just after Passover, the Germans invaded Hungary, my father’s family was moved into a ghetto and then transported to Auschwitz. My father, like many other young and strong Jewish boys, was forced into a civilian labor battalion under the control of the notorious Hungarian gendarmes.

In the winter of 1944, as the Russians came closer, his labor force was moved towards the German territories to avoid being captured by the Russians. Hungarian command was transferred to the SA, the German Stormtroopers, who forced thousands of Jews, from teenage boys to men in their fifties, to dig wide and deep trenches, sometimes with their bare hands, to stop advancing Russian tanks.

During that time, my father lived day by day. The laborers knew that at any time the German guards could take them into the forests and shoot them, that their overseers were not answerable to anyone. As with many survivors, some stroke of luck — my father eschewed the word “ miracle” as implying a “chosenness” that six million others, including his parents, were denied — allowed him to survive.

On the day he was liberated, my father recalled in an interview, one of the Jewish boys saw a Russian soldier on horseback appear.

“There was such a feeling of hope that this aroused in us,” he said. “We didn’t know what to say after all the hardships we had been through.”

The exhilaration he felt was immediately tempered as my father witnessed a Russian soldier demand a watch from one of the liberated boys. “The Russians were mad about watches,” my father said. “They just took it from him.”

The Jewish boys soon recognized that the Russian soldiers were not at all moved by what had happened to the Jews during the war. In fact the survivors of the labor force were warned that Russian soldiers were on the lookout for the strong boys who had worked so hard for the Germans.

As my father and his friends returned home to search for any family survivors, they learned to sit in dark train carriages as Russian soldiers roamed the aisles fulfilling quotas for boys to take to work in the coal mines of Siberia.

My father recalled seeing Jewish boys on their knees, begging not to be taken after being imprisoned by the Germans for four years.

“They couldn’t care less,” my father said. “If they were instructed to take 25 people they would take 25 people, not caring who they were or what they had been through.”

The Soviets were the first to liberate a concentration camp in 1944, Majdanek, and Soviet troops were first to liberate Auschwitz, in January 1945. The Soviets were unmoved by the horrors they uncovered, according to Lawrence Rees, who produced the BBC documentary “Auschwitz: The Nazis And The Final Solution,” based on his book of the same name.

“They did horrible things to them,” a woman survivor who witnessed Soviet soldiers raping and killing Jewish woman told him. “Right up to the last minute we couldn’t believe that we were still meant to survive. We thought if we didn’t die of the Germans, we’d die of the Russians.”

One story in particular, buried in our own family’s history, echoes in the most disturbing stories we hear from Ukraine, even some 75 years later.

My father’s brother had married a young Jewish Slovakian woman during the war. They were approached by a Russian soldier on a train going back to her hometown in Slovakia.

The young woman, Suvi, was wearing a gold necklace.

“Apparently a Russian soldier wanted to take that gold chain,” my cousin recounted. Suvi refused. “The soldier pulled out a gun and shot her right in front of my father. Then he opened the door and pushed her out of the train.”

As a child of a survivor, it is impossible to forget what happened to the Jews who suffered at the hands of the Russians, after they had suffered at the hands of the Nazis. Those who knew my father also knew that his war time experiences defined his entire life. At this moment in history, it is our responsibility not to look away from that history, BUT unbury those memories of a shameful past and bring them back to life once again.

“What the Russians did with the Jews after the war was unforgivable,” my father said. “They were animals, not human beings, in my opinion. No one said to them that when you go out looking for workers and meet Jews, you must be good to them because they were persecuted. They figured that anyone who had not been able to resist the Germans, would not resist them.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO