People actually prefer live Jews, really

Horn’s focus on all the ways society has failed Jews may be electrifying, but ignores a more complicated truth

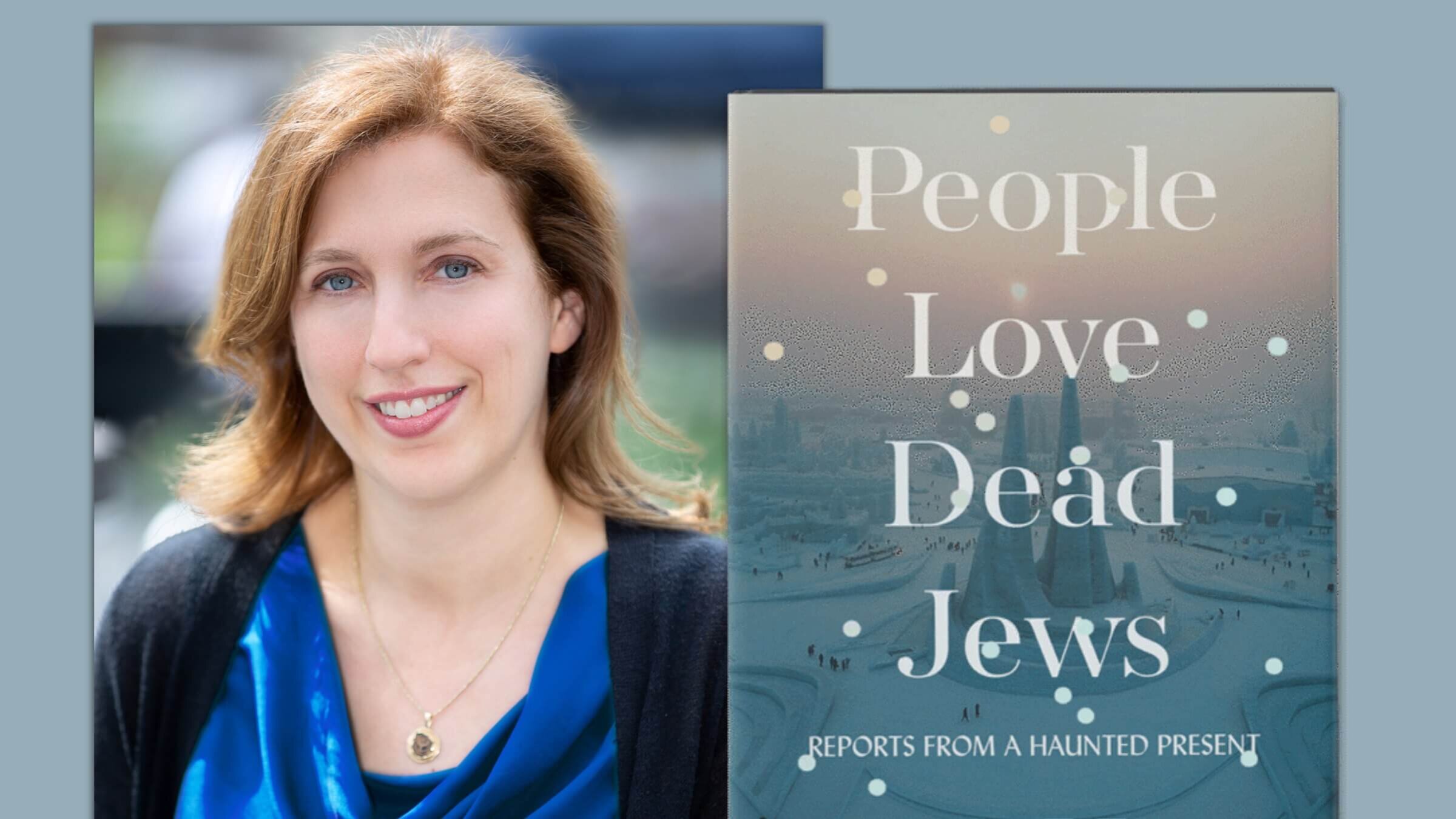

Dara Horn and the cover of her book, People Love Dead Jews. Graphic by Matthew Litman. Photo by Michael Priest.

Gerda Weissmann Klein, a survivor of three concentration camps, wrote in her autobiography that one of the ways she persevered was by imagining “a world of beauty and love.”

When I reread that quote upon Weissmann Klein’s death this week at age 97, I thought, “Uh-oh, what would Dara Horn think?’

Horn is the author of “People Love Dead Jews,” which on Wednesday received a 2021 National Jewish Book Award. It’s a deeply researched, powerfully written and provocative book, deserving of its runaway success and awards.

It’s also a book that’s been bothering me ever since I read it.

The book’s premise is that people memorialize dead Jews in ways that prevent us from understanding the reality of their suffering and blind us to the real issues living Jews face today.

Exhibit A for Horn is Anne Frank, whose story is taught to schoolchildren emphasizing her famous quote about still believing that people are good at heart. But, Horn points out, Frank wrote that line before she was captured and sent to Bergen-Belson, where “she met people who weren’t.”

When Horn recounts her visit to a virtual museum of a destroyed Damascus synagogue – or rereads “The Merchant of Venice,” or visits a bizarre theme park in Harbin, China, memorializing the Jews who once lived there – she returns to the point that Jewish history is often repackaged in a way that is uplifting, leaving out the bloody, brutal end of the story.

Horn doesn’t stop to consider that mythmaking and meaning-making is what people do in the absence of real knowledge or experience. What do movies, books and National Park gift shops teach us about Native Americans? “People Love Dead Indians” would be a multivolume book.

But Horn seems to assume this is just a Jewish issue. A visit to a for-profit high-tech museum exhibition on the Holocaust drives the point home for her. At the conclusion of the exhibit, survivors come on screen and talk about the need for people to love one another.

Horn claims that in all her readings of Holocaust survivor accounts in Yiddish, she never heard the word “love” — and argues that the exhibit there is an example of how society uses the Holocaust not to tell the truth of Jewish suffering, but to paper over the horror with uplifting lessons.

“And I find myself furious being lectured by this exhibition about love ,” Horn writes, “as if the murder of millions of people was actually a morality play, a bumper sticker, a metaphor.”

The problem is that the people who spoke of love were the survivors themselves. And unlike Anne Frank, they were well aware of how the story ended. The museum didn’t manufacture their messages. I’ve interviewed dozens of survivors, and when asked to come up with lessons, they often alight on the importance of tolerance, understanding and love.

“The salvation of man is through love and in love,” writes Viktor Frankl, who survived Auschwitz, in “Man’s Search for Meaning.”

I don’t know what Horn would make of Frankl, or of Weissmann Klein, but I do know their quotes don’t neatly fit her conclusion. What Horn dismisses as a saccharine attempt to prettify dead Jews is, for many survivors, the most profound lesson of the camps.

That’s one example where Horn rushes by evidence that doesn’t fit her argument, but the most egregious one comes when she turns her prose to living Jews.

American Jews are at a dangerous moment in history, she tells us, when the lessons of the Holocaust have receded from society’s memory and with them the taboo against persecuting Jews.

“Antisemitism is once again the next big thing,” she writes, adding later that hating Jews is now normal. “And historically speaking, the decades in which my parents and I had grown up simply hadn’t been normal. Now, normal was coming back.”

This is the book’s most resonant take-away, helping the title become a hashtag. After three Israelis were murdered by Palestinian terrorists last week, a professor of Jewish studies tweeted, “Hello void, it’s been hours since the news broke, where is the outrage?! #peoplelovedeadjews.”

But here’s the misleading part: the vast majority of people like living Jews, they really do. As Horn acknowledges, governments and the public stood by Jewish communities when they faced attacks in Pittsburgh, San Diego, Monsey and elsewhere. The rise in online antisemitism and actual violent attacks should alarm us, no question, but Jews are far from alone in fighting back.

By numerous measures, negative feelings toward Jews were actually higher in the years Horn thinks of as normal. When a 2017 Pew Research Forum survey asked Americans what faith group they felt warmest toward, 67% said Jews, more than any other group. In America, in 2022, hating Jews is deeply abnormal.

I get it: “People Like Live Jews More Than Any Other Religious Group” is a terrible book title. But it’s a fact, and Horn’s morbid focus on all the ways society has failed Jews may be electrifying, but ignores the more complicated truth that in America and, by the way, Israel, we are nowhere near the end of the story.

This column originally appeared in the Forward’s weekly “Letter from California.” To receive it click here.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO