How is the Russia-Ukraine war different from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict? Let me count the ways

Courtesy of shutterstock

This is an adaptation of Looking Forward, a weekly email from our editor-in-chief sent on Friday afternoons. Sign up here to get the Forward’s free newsletters delivered to your inbox. Download and print our free magazine of stories to savor over Shabbat and Sunday.

Perhaps you’ve seen the Twitter posts: paired photographs of a Ukrainian and a Palestinian, each hoisting a flag in a war zone, or a cartoon showing Molotov cocktails with the same flags, one side labeled “hero,” the other, “terrorist.”

Or maybe you — or your kids — are wondering about the photo rocketing around Instagram of a white-haired woman with an all-caps sign saying, “FROM UKRAINE TO PALESTINE, OCCUPIERS HAVE NO CLAIM.”

You may have heard about the supermodel Gigi Hadid donating her Fashion Week earnings “to those suffering from the war in Ukraine” and “those experiencing the same in Palestine,” and about Vogue magazine cutting out the reference to Palestinians in its coverage of her move. (We had a bit about this in Thursday’s “Forwarding the News” briefing.)

An Irish member of Parliament made a fiery speech calling out the West’s “double standard” on sanctions against Russia but not Israel, and a British Labour MP was slammed by colleagues for comparing the two situations.

I’ve seen a smattering of this in my own inbox. If Vladimir Putin “would treat a conquered Ukrainian people as inhumanely as Israel is treating those who also have a legitimate claim to that land,” one reader wrote in response to last week’s column, “the world would be aghast and would try mightily to end that treatment.”

Get the Forward delivered to your inbox. Sign up here to receive our essential morning briefing of American Jewish news and conversation, the afternoon’s top headlines and best reads, and a weekly letter from our editor-in-chief.

As Russia’s brazen and terrifying assault on Ukraine grinds into its third week, some Palestinians and their supporters are drawing dubious parallels between the current crisis and the ongoing one that plagues the holy land. The backlash from the pro-Israel right is, predictably, harsh and in some cases equally distorted.

But liberal Zionists who are deeply committed to ending the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, resolving the humanitarian crisis in Gaza and supporting Palestinian national aspirations should not apologize or feel any guilt for their urgent and grave worry about what this new crisis in Eastern Europe portends.

You can hold concern for both Ukraine and the Palestinians at the same time, just as you hold your belief in the need for Israel to survive as a Jewish and democratic state alongside your desire for the Palestinians to have an independent homeland of their own. You don’t have to devote equal mental energy, time or money to different issues at all times regardless of the news cycle.

And the two conflicts are wildly different.

Some of those trying to leverage the current moment to garner support for Palestinians are making a broader racial argument. They note the starkly different international responses, by both governments and individual citizens, to Ukraine, whose population is white and overwhelmingly Christian, versus recent wars and refugee crises affecting Black and brown people and Muslim-majority nations.

There have indeed been disturbing flares of racism in the media and broader discourse. Politicians and journalists alike have observed that the 2 million (and counting) Ukrainians fleeing Russia’s assault are “civilized,” “middle-class people,” or “just like us” — all truly offensive comments that betray a broader bias.

No doubt that white, relatively well-off, educated residents of Western democracies feel more immediate and direct kinship with the white, relatively well-off, educated residents of this Western-facing democracy than they do with the legions suffering in Yemen or fleeing oppression and economic collapse in Africa and Latin America.

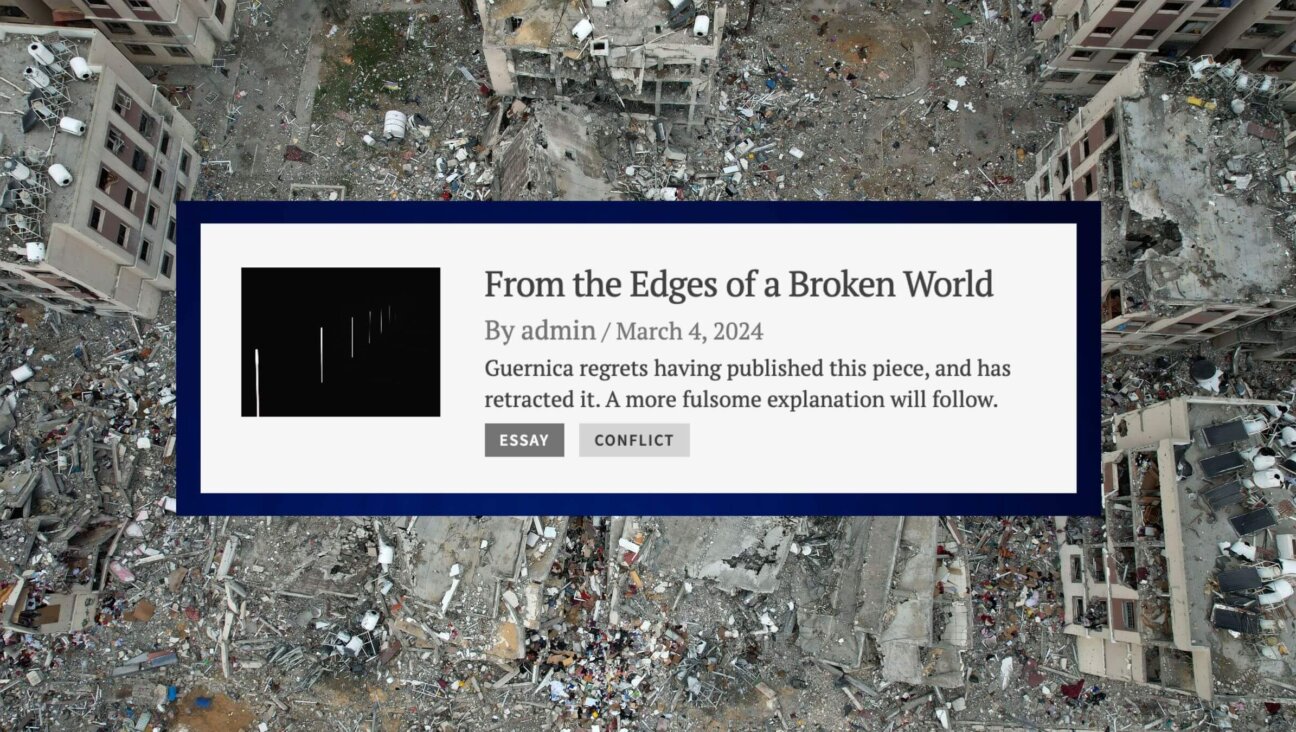

A viral photo circulating Instagram compares Russian and Israeli military actions.

Perhaps all the more so for American Jews who trace their roots to Ukraine or the larger Pale of Settlement, and have been moved particularly by the heroic leadership of Ukraine’s Jewish president and by images of rabbis holding Shabbat services in basements amid bombings or aging Holocaust survivors hobbling across the borders to safety.

And yet. We should not let that blind us to the vast distinctions in the conflicts, or the reality that this crisis has global geopolitical implications like none we have seen since World War II.

Helena (R) and her brother Bodia (L) from Lviv are seen at the Medyka pedestrian border crossing, in eastern Poland on February 26, 2022, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Courtesy of Getty

Israeli Jews and Palestinians are locked in a decades-long struggle over a land where both peoples have roots dating back centuries. Putin is not simply trying to displace Ukrainians from any particular location, but challenging their very identity as a distinct people and culture. Yes, far-right Zionists sometimes make a similar argument that Palestinians are just a subset of a pan-Arab identity, but the vast majority of American Jews and institutions do not harbor this delusion.

Russian forces are, right now, trying to take control of Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, and other key cities. Israel, in its cyclical attacks on the Gaza Strip in 2012, 2014 and 2021, has pointedly not done this, with only a minority of, again, far-right voices backing such a move.

While Israeli forces do regularly encroach on West Bank cities and towns as part of its occupation, most Israeli Jews and their American supporters want that occupation to end and adamantly oppose annexation of those Palestinian cities and towns.

What about those Molotov cocktails and flag-hoisters in the side-by-side Twitter images? In Ukraine, the citizens putting flammable liquids into old beer bottles or brandishing more serious weapons as part of the Territorial Defense Forces are aiming them at Russian soldiers invading their cities. That happens, too, when Israel attacks or invades Gaza, and is generally considered part of the reality of war.

But Palestinians also throw Molotovs and rocks at Israeli soldiers and civilians — and sometimes brandish knives or suicide bombs — in Jerusalem and other Israeli cities during periods of relative quiet, outside of anything you could call an active war. It is those attacks that are much more widely seen as terrorism even by liberal American Jews who desperately want to see a free and strong Palestinian state alongside Israel. Ukrainians are not attacking people in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Putin has criminalized journalism, threatening 15-year prison sentences for anyone who even calls this war a war, prompting the closure of independent Russian news outlets and the exodus or silencing of journalists from The New York Times, Bloomberg News, CNN and other international organizations.

Israel has a military censor, but even in the most heated battles it rarely acts to restrict international correspondents, and the country’s free and vibrant press generally covers all sides of the ongoing conflict, with left-leaning outlets like Haaretz and +972 regularly chronicling the daily, dehumanizing impact of the occupation on Palestinians.

And, perhaps most importantly, the implications of these two conflicts on the broader world’s security, economy and freedom are just not comparable.

The holy land is a place of spiritual, emotional and intellectual importance to Christians, Muslims, and Jews, so what happens there matters to many, many people. Russia is a nuclear superpower with an increasingly unstable and dictatorial leader. Putin’s next targets could well be other former Soviet republics or satellite states like Poland, Romania or Lithuania, all now members of NATO. This could literally lead to World War III.

So, yes, the strict and spiraling sanctions the U.S., Europe and other countries are inflicting on Russia and individuals close to Putin are a stark contrast to those governments’ general rejection of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement against Israel.

That is partly because the BDS platform includes language aimed not only at ending the occupation but at undermining Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish homeland — something the U.S. and Europe does not support. And it’s partly because the stakes are much, much higher.

Ukrainian refugees arrive from their homeland at Zahonyi railway station close to the Hungarian-Ukrainian border. Courtesy of Getty

When I asked my local focus group, aka my 14-year-old daughter, whether the “Ukraine is Palestine” theme was populating her Instagram and TikTok feeds, she said she’d seen a lot more posts comparing Putin to Hitler, which she found problematic. It’s been drilled into her, as it has with many Jews, that comparisons to the Holocaust are off-limits — and often inherently antisemitic — since we see that as a singular horrific tragedy.

We ended up having an interesting discussion about the inherent dangers of comparing any two disparate situations — and the deeply human instinct to do so. It’s not wrong to look to history for context to help parse current events; it’s essential.

And yet. This kind of thing often quickly descends into “whataboutism,” a logical fallacy that Merriam-Webster added to its dictionary in October and generally involves deflecting an accusation or argument by questioning why the opponent doesn’t care equally about another possibly analogous situation.

Interestingly, whataboutism generally comes up in the Israeli-Palestinian context from the pro-Israel right. What about Turkey’s occupation of Cyprus? What about China’s oppression and genocide of the Uyghurs? What about Tibet, what about Yemen?

I get asked these things virtually every time I speak at a synagogue and at many a Shabbat dinner — why do news organizations and activists and social media and the United Nations spend such a disproportionate amount of time on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict compared to these other places?

I have a two-part answer. First, as I said above, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is happening in a place of historic and psychic significance to more than half the world’s population. The disproportionate news coverage of the conflict reflects the disproportionate investment in it by the U.S. government and American Jewish philanthropists and its outsized importance in our politics.

And: Advocates have the absolute right to choose their causes. Even if they care equally about all human suffering, they do not have to devote equal time, money or energy to each incarnation of it. Of course an individual’s identity or connection to a place or people will frame their political priorities.

So, I respect those Palestinians and their supporters who view the Ukrainian crisis — and perhaps every war, every refugee, every news event — at least in part through the lens of their own serious and urgent agenda.

But that should not detract from the vital need for all of us to stand in solidarity with Ukraine and against Russia’s grave and existential threats to what we hold dear.

Your Turn: Ukraine

Thanks to the dozens of readers who shared stories of their roots in Ukraine or other reflections on the crisis. Sol Karsch told how his bubbe helped his uncle escape military service at the dawn of World War I by sneaking him off an army base in a dress (“What a Jewish mother does not do for her children!”). Laura Kaufman wrote about her grandfather, Irving Rozamovitch Karol, one of hundreds of Ukrainian Jews orphaned in WWI and adopted by North American families.

Your Weekend Reads

Download the printable PDF of our free magazine of the week’s top stories here. Or, read them online at the links below.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO