We’ve debated ourselves into irrelevance over liberalism and Zionism

Image by Noah Lubin

There are two versions of the story we tell ourselves about the increasingly curdled romance between a sizeable chunk of American Jews and the Jewish State. If you’re on the left, you probably believe that somewhere along the way, Zionism lost its liberalism. If you’re on the right, you probably believe the opposite, that liberalism turned on Zionism. Pick your victim, choose your villain. The irony of course is that both left and right seem to agree that tension between the ideals of liberalism and those of Zionism is the reason it’s always awkward to talk about Israel in Brooklyn, especially on dates.

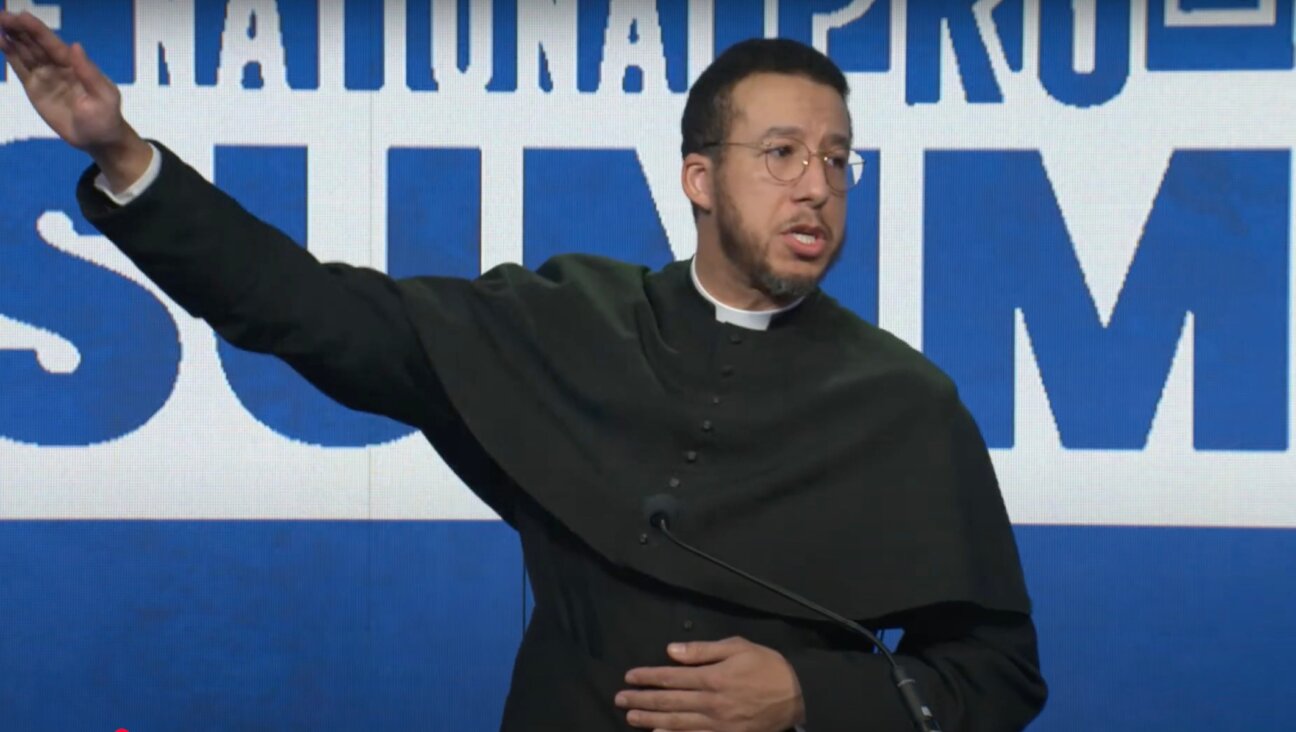

Ari Hoffman Image by Noah Lubin

Given how much consensus there is that Zionism and liberalism are on a collision course, it’s not surprising that this view has become canon. And the idea, popularized by Peter Beinart on the left and Elliott Abrams on the right, is not entirely incorrect. But it misses the forest for the trees.

The truth is, the story we American Jews have told about ourselves over the past decade has been a self-involved, local affair, a myopic misreading of a sideshow as the main stage. The past decade has seen debates about Israel and Zionism broadcast to the largest possible audiences; it’s not just about us anymore.

The crisis of Zionism and liberalism has become big business. It’s taken center stage in our politics and culture. It now partakes of the habits and chaos of that larger canvas.

And it is precisely the solipsism of American Jews, and the simple stories we tell ourselves, that makes us ever more irrelevant, lost in a blame game with no winners.

*

Ten years ago, halfway into the first Obama term, a piece by Peter Beinart in The New York Review of Books titled “The Failure of the American Jewish Establishment” warned of an impending divorce between liberal Jews and the Jewish Establishment, capital “e”. Beinart’s argument was blunt: If American Jews were required to choose between their liberalism and their Zionism, as an increasingly illiberal Israel with its endless West Bank occupation seemed poised to make them, it would be support for Jewish self-determination that would be cut loose. “For several decades, the Jewish establishment has asked American Jews to check their liberalism at Zionism’s door, and now, to their horror, they are finding that many young Jews have checked their Zionism instead,” he wrote. An eye for an eye, in a revolving coat check of ideological priorities.

Per Beinart, these developments were lost on American Jewry’s leadership, the titular “Establishment” who were too busy bulking up to “make themselves intellectual bodyguards for Israeli leaders who threaten the very liberal values they profess to admire.” These Upper East Side bouncers “patrol public discourse, scolding people who contradict their vision of Israel as a state in which all leaders cherish democracy and yearn for peace.”

Parroting a “fake,” zombie liberalism, Jewish American leaders were in fact tied at the hip to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s revanchism, something real liberal Jews were getting wise to and which was making them slowly abandon their Zionism, Beinart argued. Instead of confronting their own hypocrisy, the Jewish establishment turned to Orthodox Jews, purveyors of a Zionism with a “distinctly illiberal cast.” In other words, the Goths were at the gates of Rome, and once they took over the city, the Zionism on offer would start to look less like the Zionism stocked at Zabar’s and more like that on tap in the West Bank. American Jews would be left with a Zionism that had given up on liberalism and a liberalism that had given up on Zionism — a mutually acrimonious divorce.

The piece, later expanded into a book, “The Crisis of Zionism,” is treated in American Jewish circles with a reverence usually reserved for divination, given the way things have developed since. And six years later, Beinart’s warning from the left was met with a complementary analysis from the right: an essay by Elliott Abrams in Mosaic Magazine. Like Beinart, Abrams begins with the breach between American Jews and Israel. But where Beinart sees a changing Israel leaving American liberals in the lurch, Abrams reversed the causation: It wasn’t an illiberal Israel that had abandoned liberal Jews, but rather liberal Jews who had abandoned Israel.

“The beginning of wisdom is surely to understand that the problem is here, in the United States,” Abrams wrote. “The American Jewish community is more distant from Israel than in past generations because it is changing, is in significant ways growing weaker, and is less inclined and indeed less able to feel and express solidarity with other Jews here and abroad.”

For Abrams, a weakening relationship with Israel was a symptom, not a cause, of a more general rot in the Jewish body politic. Forget about the status of the West Bank or the intricacies of the latest coalition government, Abrams argued, and focus on intermarriage rates, synagogue attendance, and the broader commitments to Jewish life and letters. If young American Jews see something unpalatable when they look at Israel, it is because of the styes in their own eyes.

If you spend any time on Twitter or in meetings with Jewish non-profit executives, you will at once note the seemingly prophetic nature of Beinart’s account from a decade ago, and the prevalence of Abrams’ inverted take. Young Jews are abandoning Israel in droves, we’re told again and again. It seems that the only debate is over who to blame.

So who got it right? (No one.) Have we become who we thought we would become, or something unrecognizable? (A little of each.) At this moment of communal suspension, what is our portrait? (Keep reading.)

*

Of course, Beinart and Abrams got some things right. The divorce between liberalism and Zionism has been finalized, the settlement agreement signed in a fit of acrimony. A new unity government in Israel flirts with annexing parts of the West Bank, with the Trump Administration as wing man.

Meanwhile, American Jews, especially the young, find themselves votaries of commitments to marginalized communities, causes, and politics that preclude their allegiance to the Jewish State. Today’s Jewish scene is a fun house, albeit less revolutionized than exaggerated. It is a hopped up version of the one that Beinart warned was on its way to being born and that Abrams saw as latent in the disordered and decaying Jewish civilization of the New World.

And yet, the strain and split between liberalism and Zionism requires a deeper understanding of both right and left than Beinart or Abrams offered.

The truth is, we’re a side show. While Jews may think we are center stage in the currents which pit today’s ideologies against each other, we are far from it. America itself is engaged in a much bigger battle, to which our pet issue has been conscripted. Thus, we are repeatedly told that though Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders lost the democratic primary to Joe Biden, he won the ideas primary, and in the meanwhile introduced a host of new voices into the national conversation who were stridently critical of Israel.

Meanwhile, RSVPing for AIPAC’s annual conference has become one of the most fraught decisions in American politics, and the organization itself has gone from bipartisan bastion to partisan hot potato. This, too, is not about us, but about much larger currents determining what left and right mean in the U.S. in 2020.

Certainly, Zionism has become anathema to the American left. “Zionist” has become a dirty word, an unforgivable ideology invoked only as a slur or insult. People admitting their Zionism are subject to severe attacks and censure. The result is that for many young Jews, their Judaism is not synthesized from a conversation between liberal conviction and Zionist demands, but is rather forged from the battering critique that can be leveled against Zionism. Groups like Jewish Voice for Peace and IfNotNow remain on the fringe, but they are held up again and again and again by the stars of the left as paragons of virtue. The message is clear: There’s only room for one kind of Jew on the left.

As Ethan Bronner wrote recently in The New York Review of Books, “There can be little doubt that the left, including American Jews on the left, increasingly rejects not only the occupation but the very concept of a Jewish State.”

If the center is holding at all, it is a little bit like Joe Biden’s candidacy — more resilient than you think, less robust than you’d like, and generationally rearguard.

But it is not only the left that has undergone an extreme makeover in the last decade. A larger rightward shift in the center of Zionist gravity, both here and in Israel, has transpired. Beinart sketched the right as predominantly Orthodox, trending towards greater conservatism in matters of both faith and politics. This is undoubtedly true. But what has happened is far more dramatic than that.

The last ten years has been the story of the right coming in from out of the cold into the light and warmth of the political spotlight. President Trump’s son-in-law and advisor Jared Kushner, whose family has donated to American Friends of Beit El and put Netanyahu himself up in Jared’s bedroom, now calls the shots in the West Wing. Ambassador David Friedman and former envoy Jason Greenblatt likewise come from precincts of the American pro-Israel world that have stormed the gates and redecorated the decor. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who is set to visit Israel this week, runs American foreign policy with a Bible open on his desk, turned to the Book of Esther.

Like Mordechai and Esther, we Jews are memorable yet provincial players in an empire too large to imagine.

Meanwhile, in the Promised Land, the remarkable thing about the past ten years is how little has changed, a stasis that screams consensus. Netanyahu is somehow still in power, and if anything, his base of support and Israel’s political weather have only moved farther to the right; John Kerry’s push for peace seems like far more than a century ago, in political lifetimes. The series of elections between Netanyahu and his Blue and White challenger Benny Gantz featured hardly a whisper about policy towards the Palestinians. The action in Israeli politics now is all between the center and the right; the Labor party has literally ceased to exist; left wing politics has largely become an affect rather than a real political force.

While members of the American left who have come of age in the past decade live in the past, uncomfortable with the founding of the State and trying to ideologize it out of existence, most Israelis live firmly and squarely in the present. And that present is infected with the reality of Gaza’s continued antagonism, the menace of Hezbollah, and the region-wide malevolence of Iran.

All of this is to say that a paradigm that does not account for acceleration at every point will fail to describe reality. The old ways of seeing might describe the way things are, but it will be helpless to prescribe how to capture the future.

*

Who has changed, the left, or Zionism? And if the inevitable answer is that they both have, which horse is worth the bet?

There’s a tragedy to today’s conversation and the way it pits Zionism and liberalism against one another. Recall that Zionism invited in liberalism at its ground level. The founding fathers of Zionism were liberals of the old school, in the grand European tradition; Herzl was a drama critic who titrated the best of 19th century continental thought into pamphlets on the need for a Jewish homeland. Vladimir Jabotinsky, though now a revered figure on the right, was a belletrist and classical liberal who consistently stood for freedom of speech and took Palestinian national aspirations seriously.

Today’s left would be unrecognizable to this tradition, with its suspicion of speech and its instinct towards dogma rather than conversation. The cause of Jewish liberation has gone from being a core of left-wing politics to its bête noire.

But Zionism too, has changed, since its early Viennese and Warsaw varieties that were mixed from ancient Psalms and cutting-edge nationalism and synthesized from ancient texts. Today, when American Jews look to Zion, they no longer see a beat that resembles their own. As Matti Friedman and Yossi Klein Halevi have persuasively argued, Israel is becoming more Middle Eastern by the moment. And of course, the great spoiler, Avigdor Lieberman, draws support from the million Russian Jews on the other side of the Iron Curtain, whose experience under Communism, and subsequent secular yet hawkish politics, American Jews have never fully understood or internalized.

It is precisely the solipsism of American Jews, their tsk-tsking, that makes them ever more irrelevant. Arab Israelis have never been more empowered. Israel has never been stronger regionally and culturally. It continues to command high levels of identification and support among American Jews, even as dire warnings about the unsustainability of the occupation continue.

Israel will emerge from Covid-19 an improbable success story, even as the US remains in the throes of terrible suffering. Its economy has gotten more dynamic and its start-up scene more turbocharged even as its politics has moved to the right and its center of gravity has grown more religious. Even Aliyah is increasing.

These facts are not dispositive in any one political direction. But they do comprise a list of particulars that have to be reckoned with by those who want to tell you about the end of the world. If you are going to make the case for crisis, you had better explain why success is a mirage.

*

In the face of these changes and non-changes, how have Jewish American institutions, ostensibly built for the long run of history, fared in the past decade? Their harshest critics see them as Weimar custodians, haplessly alienating American Jewry’s left flank while capitulating to its right one, lining up behind the Israeli government over there rather than keeping their finger on the pulse of things over here. The result, they argue, is a suite of institutions both ineffective and ideologically awry, a bystander to the abandonment of Zionism and an inadvertent facilitator of that very leave-taking. Guilt can stain wringing hands just as well as steady ones.

Are these critics correct? Certainly, some organizations have failed. AIPAC has gone from being a pro-Israel cheerleader to a political football. It can be said to have flunked the final exams of both the Obama and Trump Administrations. It was against the JCPOA, only to have it pass, alienating Democrats in the process. And in the Trump era, it has failed to hold the center, doing little to counter being painted into a far-right corner. It takes special ineptitude or particularly stormy seas to sail square into both Scylla and Charybdis.

AIPAC is not the only organization that has stumbled. Most recently, the Conference of Presidents (full disclosure: I am on the organization’s Young Leaders Division), ostensibly a unity body, was riven apart by acrimony between its member organizations over the appointment of a new chair, with Diana Loeb of HIAS setting off Mort Klein of the ZOA’s alarm bells and tweeting instincts. While a compromise was reached, the dirty laundry cannot be unseen, and is undoubtedly a harbinger for further discord to come.

Hairline fractures and clean breaks are evident elsewhere as well. Hillel, while continuing to offer invaluable services and community to Jewish students on campus, has come under fire for trying to hold the Israel line, satisfying neither the right nor the left. The ADL has found itself caught in a similar vise as an organization birthed in consensus that seemingly alienates a portion of its constituency every time it wades into the news cycle.

Of far greater peril for these organizations than the burn of controversy is the chilly indifference of irrelevance. As Joel Swanson argued recently in these pages, these organizations aged into irrelevance even before the cataclysm of the corona crisis. “The truth is, these organizations will struggle to rebuild after this crisis ends because they simply aren’t relevant to the lives of American Jews any longer,” writes Swanson. “The American Jewish establishment is politically obsolete.”

It may be that our organizations have failed us, or that we have failed them. They need to be edgier; we need to be more interested, more curious.

But a sense of frustration with American Jewry’s organized arm must not shade into their total abandonment. It is easy to deride the center, until you lose it; bronze may not seem so great until you are living with disposable plastic.

Writers on the left see hypocrisy everywhere — in unconditional support for Israel, in dodging the question of annexation, in not being sufficiently attentive to the rights of Palestinians. The only path forward for Jewish organizations that would satisfy the left is if these institutions would participate in their own immolation. Out of those ashes the left hopes will rise a chastened American Jewry, having set aside the childish playthings of their Zionist delusions.

But I think there is another way forward that acknowledges that the failures of American Jewry do not negate the intent or ability of the enemies of the Jews to inflict very real harm. Taking those enemies seriously must be the first principle of any Jewish strategy worth its salt.

Second, the left can no longer claim to be the passive victim of abandonment. Its commitment to Israel needs to be the starting point of its criticism of the Jewish State, not the thing it views as an impediment to a utopian future. Third, the “Jewish Establishment” needs to find answers, fast.

What we need is passionate, seeking Jews who demand the same of the bodies that represent them.

Ari Hoffman Image by Noah Lubin

The pressing matters of global pandemic and crashing economies demand all the attention we can give, and then some. And a resurgence of anti-Semitism has raised the oldest ghouls of history.

Against these headwinds and in the face of these microbes, each one of us must bend our shoulder to the task of remaking the world. But that must not mute the conversations that came before.

We have so much to figure out. The world is changing, and the Jews, like the entire suffering and shuttered human tribe, need to plot their uncertain course forward.

Ari Hoffman is a contributing columnist at the Forward, where he writes about politics and culture. His writing has also appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Tablet Magazine, The New York Observer, Mosaic Magazine, The Jerusalem Post, The Times of Israel, and The Tel Aviv Review of Books. He holds a Ph.D. in English Literature from Harvard and a law degree from Stanford.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO