We are the Egyptians now

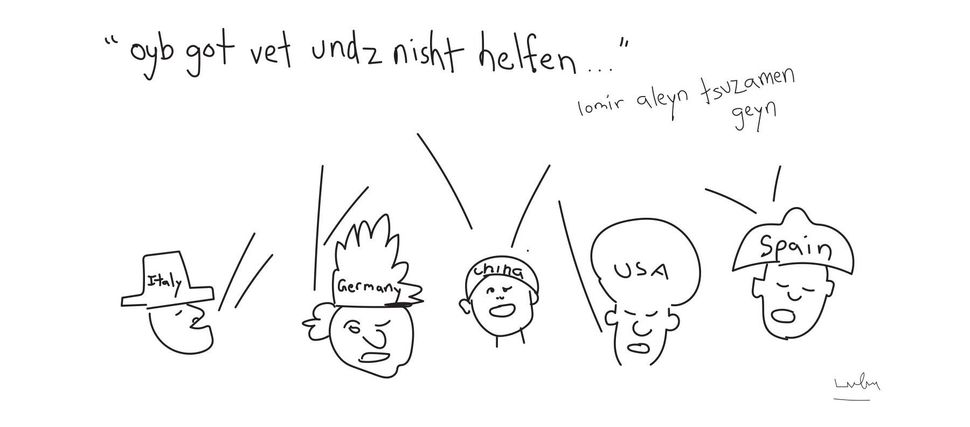

Image by Noah Lubin

And Pharaoh turned and went into his house, neither did he lay even this to heart. And all the Egyptians digged round about the river for water to drink; for they could not drink of the water of the river. (Exodus 17:23-24)

What did Pharaoh tell his people? Did he downplay the severity of the events? Did he promise it’d all be over soon? That the markets would come roaring back? That his healers were the most powerful magicians in the land? Did the people understand the connection between the sludge in their streams and the oppression of all those immigrant workers, toiling away on the pyramids?

The plagues were about power. The middle act of our great old epic of bondage, infanticide, torture, exile, exploitation, collective punishment, fever dreams, and dominance. For Egypt, the assertion of divine authority came through suffering and pestilence. The miraculous was experienced as a baffling curse, a nightmare of hunger and wonder.

The LORD of the alien slaves had poisoned the water. That which brought life, brought disease and death. The Nile turned red, the fish choked, and the Egyptians thirsted. Dam, blood. It lasted seven days.

Daniel Kahn | Photograph: Oleg Farynyuk

Didn’t they see that it was their own Pharaoh who brought this upon them, with his vanity, his ignorance, and pride? Or did it make them hate the slaves even more?

What was it like that morning, when average Cairo taxpayers woke up to find their wells black with coagulate? Did they attempt to wash with it? To drink it? Did they sense that this was only the beginning of Moses’ campaign of foreign supernatural terror?

Over the following weeks, every Egyptian would be stricken in helplessness. Their empire would become a wasteland of sickness, protected by no gods.

Maybe we’ve been telling it all wrong. Dipping our fingers into the wine, counting out the plagues onto the plate. Better it should happen to them. We were the Hebrews. We were the afflicted. We were once slaves. But it was always a projection, a fantasy of revenge and redemption. We told ourselves that it somehow connected us to all the oppressed in the world. We sang Let My People Go and reclined in our freedom. Dayenu.

Well, let this be the year when we see that, alas, we are not the Hebrews. We are all Egyptians. A new wrath is upon us.

And that which had bound us together, our commerce and communion, has become a source of disease and death.

As a public service during this pandemic, the Forward is providing free, unlimited access to all coronavirus articles. If you’d like to support our independent Jewish journalism, click here.

Yet as national and physical borders are closed, other borders dissolve in a great collective of isolation and fear. We are now bound ever tighter, in the solidarity of our vulnerability. As in the old Yiddish revolutionary song, “oyb Got vet undz nisht helfen … lomir aleyn tsuzamen geyn,” or, interpreted liberally, If God will not help us… let us travel together alone.

This plague is only the beginning. It’s gonna take more than this to soften the Pharaoh’s heart. Maybe it’s gonna take the blood of someone he knows personally, maybe his own. As in Exodus, his gods will not save him. No one can count on being passed over.

We are aleyn tsuzamen.

This is one in a series of pieces on Passover during coronavirus. Read the rest of the series here.

Daniel Kahn, born in Detroit, is a Berlin-based singer-songwriter, theatre artist, and translator, working in Yiddish, English, and German.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO