Why Juneteenth, which marks the end of slavery, should be a Jewish holiday

For American Jewry, celebrating civic holidays “has symbolized our commitment to the American project,” writes Tema Smith

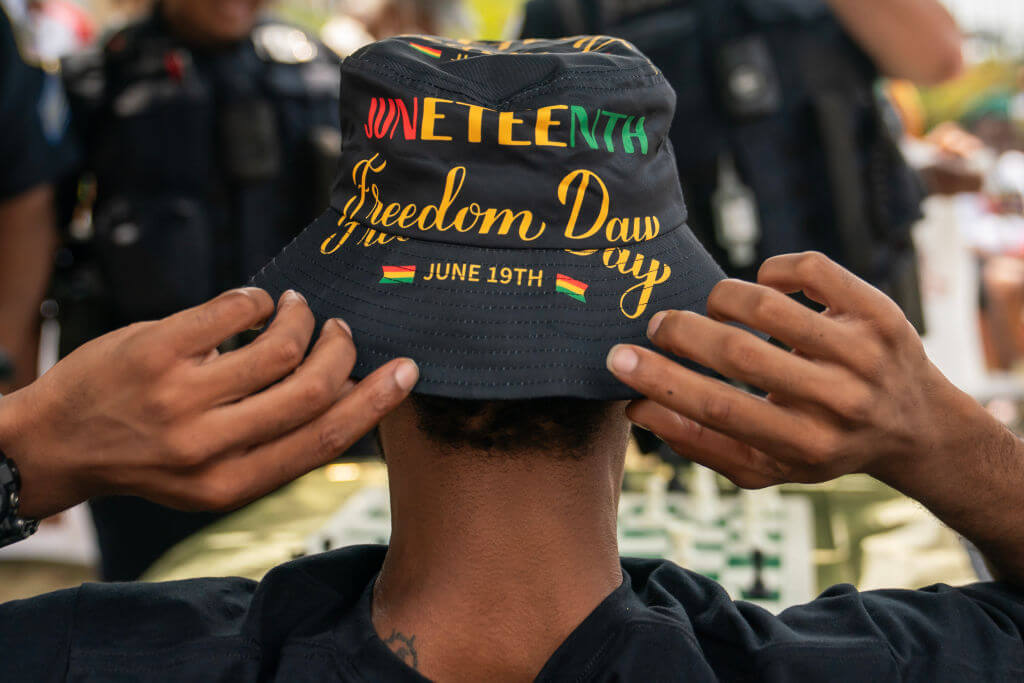

An attendee adjusts his hat during a neighborhood Juneteenth festival on June 17, 2023 in Washington, DC. Photo by Getty Images

This week, African Americans will mark Juneteenth — a portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth” — a holiday commemorating the freedom of their ancestors from chattel slavery. This year, it is time for the Jewish community to join them.

All across the country, black communities will parade, will feast, and will pay respect to the ancestors, among other activities. This will take place again this year, as it has in the years before it, despite the fact that to this day there is no national commemoration of emancipation in the United States, not on June 19th or on any other federal holiday on the calendar. Juneteenth, celebrated nationally even without official standing, has come to mark both the end of slavery and the ongoing struggle for civil rights in America.

It is impossible to deny the role that chattel slavery played in the history of the United States — both in terms of building the country, and in the triumphalist narrative of good over evil that would come to characterize stories of the Civil War, where the North is said to have fought for the moral character of the nation.

There is no official commemoration of the emancipation of some four million enslaved people — almost 90% of the black population of the US on the 1860 census. It tells the story of a nation not yet ready to deal directly with slavery’s enduring legacy.

To this day, the echoes of chattel slavery can be found throughout American society. Racial divisions plague us, whether in maternal mortality rates, the school-to-prison pipeline, income disparity, or the persistence of the wealth gap, among some of the more oft-cited measures. And yet, we often struggle to even talk about the roots of these inequalities in any meaningful way.

The story of Juneteenth itself can be read a metaphor for the fact that it is not yet marked on a national level. Despite the Emancipation Proclamation having taken effect over two years prior, on January 1st, 1863, the slaves of Texas toiled until Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger issued an order freeing them in Galveston, Texas on June 19th, 1865. Texas was the last stronghold of chattel slavery in the former Confederacy.

Slavery in Texas did not end on the day the order was issued. Freedom was hard won. As historian Henry Louis Gates explains, “On plantations, masters had to decide when and how to announce the news — or wait for a government agent to arrive — and it was not uncommon for them to delay until after the harvest. Even in Galveston City, the ex-Confederate mayor flouted the Army by forcing the freed people back to work…”

The 19th of June, then, as an heir to the tradition recounts, “wasn’t the exact day the Negro was freed. But that’s the day they told them that they was free…”

It wouldn’t be until later that year, December 6th, 1865, that slavery would officially end in the United States with the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment, which set free the last people still enslaved by slaveowners clinging onto the last vestiges of chattel slavery.

Juneteenth, more than anything, commemorates the potential of freedom.

For the next hundred years Juneteenth was hardly known outside of Texas, except where black communities migrated, taking the tradition with them. First, it went westward. However, it wouldn’t be until the months after the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that the celebration of Juneteenth would spread widely across black America.

That year, Rev. Ralph Abernathy and Dr. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King made a decision to cut short the Poor People’s March in June of 1968, with delegates from Texas suggesting that they mark Juneteenth together on the Washington Mall. The delegates dispersed with the memory of this commemoration fresh in their mind, bringing Juneteenth back across the black communities of the Great Migration. As Van Newkirk II writes in the Atlantic, “Like many black homegoings, it found a way to fuse sorrow and jubilation. What Abernathy and Coretta Scott King knew was that fusion was the only way to continue the work without breaking.”

To this day, though, Juneteenth has remained primarily a celebration in black communities. As Professor Karlos Hill remarks, “Juneteenth is largely seen as an African-American thing; it is not seen as something for the general population … it is poorly understood outside of the African-American community. It is perceived as being part of black culture and not ‘American culture,’ so to speak.”

We are long overdue to take steps towards making Juneteenth part of “American culture,” and our very own Jewish tradition is a great place to start.

For the Jews of America, celebrating civic holidays has come to be a sign of pride and patriotism — marking these dates has symbolized our commitment to the American project. This commitment has also seen the Jewish community commit itself in turns to social justice and activism alongside the black community.

Beyond the moral imperative to mark Juneteenth, to do so would also be to show solidarity and acceptance to the growing diversity of the Jewish community. Many within our community are descended from the legacy of chattel slavery — and live every day with its enduring systemic effects.

Last year, JFREJ’s Jews of Color caucus hosted a Juneteenth Seder next to the East River where participants read together from a Haggadah prepared for the occasion, reimagining the Passover ritual for an emancipation that happened on America’s own shores. “Liberation is not something that once happened to us, in the past,” participants recited together. “It is something that must be recreated again and again, through action and imagination. Freedom is something we make, together.”

The work of liberation for black Americans is still in progress. This work is not something that can be done alone. The Jewish community must be involved, not simply because it is the right thing to do, but because our very future is bound up in it too. It is time for the Jewish community to stand next to the black Jews in our midst, and shoulder-to-shoulder with the broader black community.

Let the Jewish community take cues from black leaders who ask them to reckon with hard truths — truths like the fact that the wealth of America was built on the back of African slaves from whom our black community is largely descended. Truths like the fact that many Jews in pre-Civil War America were silent on slavery, and some did, in fact, own slaves. Truths like, while many in our Jewish community have been able to access reparations for our communal tragedy of the Holocaust, black Americans continue to fight for theirs.

We read in Pirkei Avot words of wisdom from the rabbis of the Mishnaic period. Many are familiar with the famous saying of Rabbi Tarfon that close out the second chapter of the book: “It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you at liberty to neglect it” (2:16).

Fewer have likely encountered the words that follow in the opening of the very next chapter, attributed to Akavia Ben Mahalalel:

“Keep your eye on three things, and you will not come to sin: Know from where you came, and to where you are going, and before Whom you are destined to give an account and a reckoning.” (3:1).

History. Destiny. Accountability. As Professor Hill reminds us, “a Juneteenth holiday is just the impetus and enabler of the change that we want to see. The process of creating this holiday, the change that would need to occur to get people’s minds and spirits in the right place, is really what we want.”

This year, it is time for the Jewish community to mark Juneteenth. Seek out your local Juneteenth celebration. Lobby your congressperson to make Juneteenth a national holiday. Read about the enduring impact of chattel slavery on American black communities. Commit yourself to acts of social justice that will dismantle systemic inequalities in America. This, and more, our moral tradition compels us to do.

After all, in the immortal words of Emma Lazarus, “Until we are all free, we are none of us free.”

Tema Smith is the Director of Community Engagement at Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto. You can find her tweets about Jewish community, race and identity @temasmith.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO