There Are No Winners In Steve Bannon’s Booting From New Yorker Festival

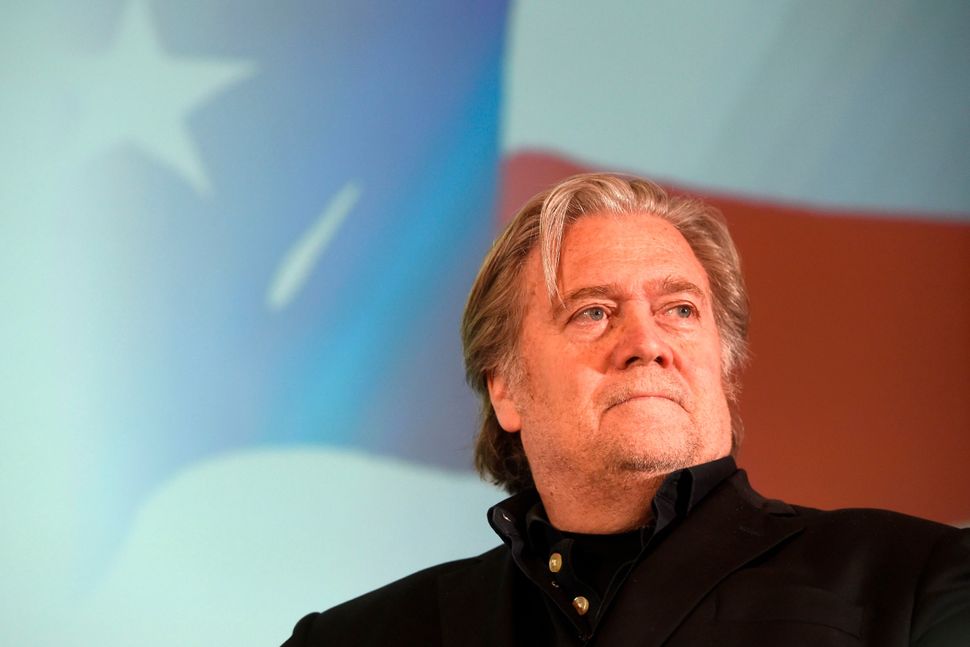

Image by Getty Images

The latest controversy over the question of public platforms for odious speakers revolves around Steven Bannon, Donald Trump’s former chief strategist and ex-publisher of Breitbart News, the Pravda of the Trumpian right. On Monday, the news that Bannon would “headline” the upcoming New Yorker Festival in early October, appearing in an interview with New Yorker editor-in-chief David Remnick, sparked a massive backlash from the magazine’s staff, festival guests, and many others in the social media.

Within a few hours of announcing Bannon’s role at the festival, Remnick announced that the invitation had been rescinded.

This fiasco is now being cited as evidence of liberal intolerance, aversion to debate, and rule by tantrum-throwing “digital mob.”

But as a strong critic of progressive groupthink and “deplatforming,” I think that in this case the charge may be misplaced.

Bannon is not simply someone with opinions that dissent from the progressive party line. He is widely and quite rightly regarded as an odious figure, even by many critics of his disinvitation.

It’s true that some of the more damning accusations against Bannon, such as his ex-wife’s charge that he privately expressed anti-Semitic views, have not been confirmed.

And yet, what’s certain is that during his tenure, Breitbart repeatedly provided sympathetic coverage to the virulently racist and anti-Semitic “alt-right” — even giving a forum to an alt-right social media figure to attack anti-Trump conservative and former Breitbart writer Ben Shapiro, a major target of the alt-right’s anti-Semitic harassment.

While much of this alt-right love-fest came from then-Breitbart star Milo Yiannopoulos, Bannon himself told Mother Jones journalist Sarah Posner that Breitbart was “the platform for the alt-right,” while downplaying the movement’s bigotry.

Bannon-era Breitbart also stoked fears of black-on-white violence, hailed the Confederate flag as a symbol of a “patriotic and idealistic cause,” and reviled even legal immigration. Bannon himself has a habit of invoking “The Camp of the Saints,” the luridly racist 1973 French novel in which white civilization is overrun by filthy, grotesque hordes of dark-skinned Third World migrants, as a metaphor for current immigration issues.

Bannon has always denied charges of racism, claiming that his nationalism is simply about putting America’s interests — particularly economic interests — first. And yet in November 2015, interviewing then-candidate Trump on his radio show, Bannon balked at Trump’s assertion that it should be easier for talented foreign students to stay in the U.S. after they graduate. To Bannon, it was a cause for concern “when two-thirds or three-quarters of the CEOs in Silicon Valley are from South Asia or from Asia.”

Add in the fact that Bannon is not someone who wants dialogue but someone who brags about wanting to “destroy” his ideological opponents. (According to conservative writer Ron Radosh, Bannon proudly calls himself a “Leninist” — a radical who wants to tear down the establishment by any means necessary.)

Add in, too, the fact that his views have had a tangible impact on real-life politics, particularly in his capacity as Trump’s guru.

Add in his defiant championship of Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore, despite credible accusations of sexually abusing underage girls.

Repugnance is warranted, just as it would be if a major magazine decided to feature a speaker who was a literal Leninist, or a jihadist. (Would conservatives call it a “tantrum” if other speakers refused to appear alongside such individuals?)

Obviously, none of this means Bannon shouldn’t be interviewed or even engaged to speak. Yale professor Nicholas Christakis, who has criticized the “heckler’s veto” in this case, tweeted that “sunlight is the best disinfectant for ideas like Bannon’s.”

And indeed, since Bannon is now in thick of nationalist/populist political agitation in Europe, confronting him with some hard-hitting questions could be fascinating. But the New Yorker festival, primarily a celebration of culture, is probably the wrong venue for such a conversation; for Bannon to be “headlining” the festival made him sound more like an honored guest than an interview subject on the hot seat.

Remnick’s original plan was to interview him for a New Yorker podcast. Perhaps he should have stayed with that idea. Or perhaps he should have done the interview onstage as a standalone event.

One could argue that Bannon should have been kept on the program out of commitment to intellectual openness — though, if open debate was the goal, it would have been far better to feature thoughtful conservatives.

But people unhappy with Bannon’s presence certainly had the right to speak out, and The New Yorker had a right to reconsider.

Of course, the trouble is that in today’s climate, it’s hard to tell where reconsideration ends and coercion begins. Australian writer and comedian Ben Pobjie, a contributor to The Guardian, may have summed it up best:

Nobody has a right to any platform BUT I think it’s usually bad to invite a speaker to a thing and then disinvite them due to public complaints BUT sometimes the original invitation was such a dumb idea that disinviting them is just good sense and Bannon falls into that category

— Ben Pobjie (@benpobjie) September 5, 2018

The invitation was bad. The disinvitation is bad. On the one hand, xenophobia-peddling, fascist-enabling populist demagogues should not be treated as respected participants in public discourse. On the other hand, allowing speakers to be dropped under public pressure creates the very real danger that people will be deplatformed simply for unpopular or controversial views.

A win for decency, or a loss for free speech? Probably a wash.

Cathy Young is a contributing editor at Reason magazine and is the author of “Ceasefire: Why Women and Men Must Join Forces to Achieve True Equality.” Follow her on Twitter, @CathyYoung63.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO