Abbas Is Wrong About Jewish History – But He’s Not Totally Wrong

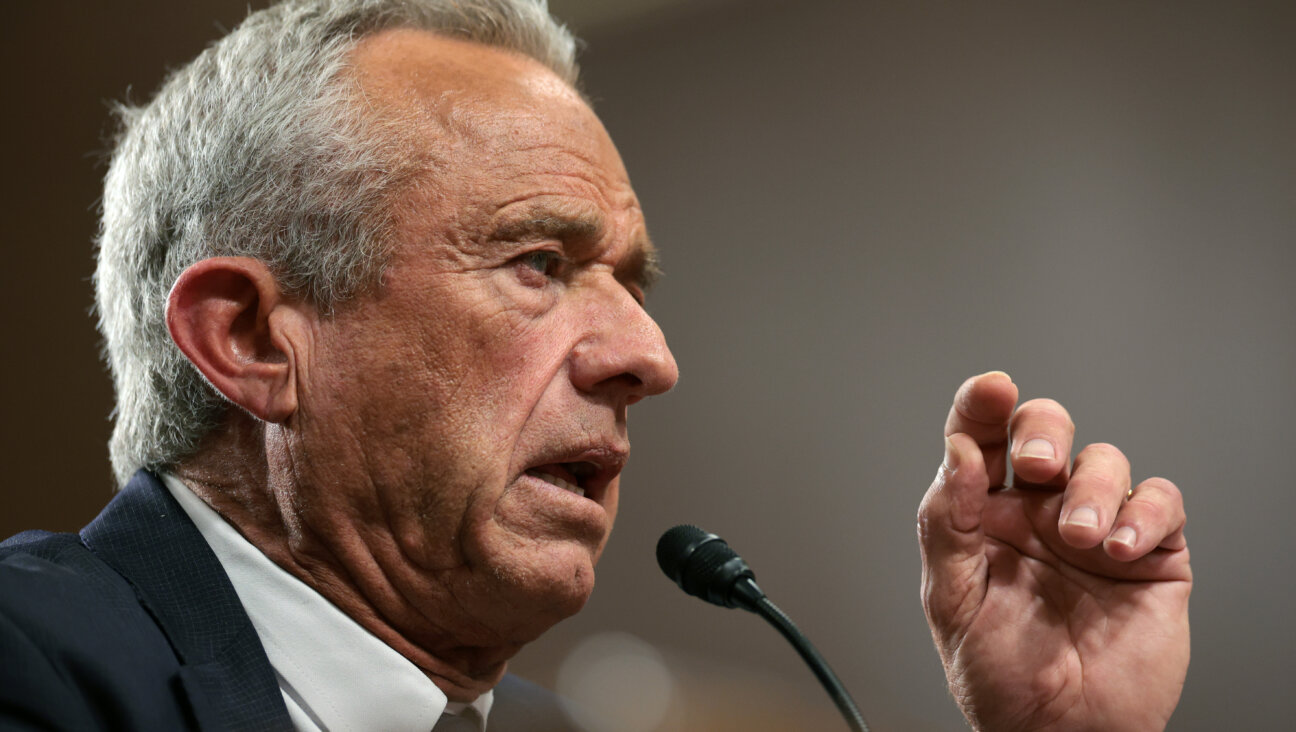

Image by Getty Images

This week, in response to the Trump administration’s declaration of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas declared in a scathing speech that “Israel is a colonialist project that has nothing to do with Jews.”

Abbas did not invent this characterization of Israel; it is a longstanding contention of anti-Zionists. Zionism’s opponents often deny a historical Jewish connection to the land. Consider a recent op-ed in Al-Hayat al-Jedida, the official Palestinian Authority daily, in which Fatah Revolutionary Council member Bakr Abu Bakr refers to “the Children of Israel” as an “Arab tribe that became extinct.” “The present residents of our land who are affiliated with the Jewish religion have no connection to them,” writes Abu Bakr. Rather, Zionists are European colonists who seized control of a land where their ancestors never lived and fabricated a history to justify dispossessing Palestinians.

This view reduces Zionism to a nefarious plot concocted by colonialists who coopted Jewish history. As such, it ignores established Jewish history and is naturally in tension with the way the vast majority of Israeli and diaspora Jews view their identity. In its most extreme version, a bumper sticker popular among right-wing Zionist residents of West Bank settlements reads, “Judea and Samaria: The Story of Every Jew”, using the biblical names for the region to invoke their centrality as settings of our ancient narratives. But this penchant for referencing ancient Jewish roots is far from exclusive to right wing settlers. Avi Gabbay, leader of Israel’s center-left Labor Party, recently voiced opposition to removing any West Bank settlements, on the grounds that “God gave Abraham the whole Land of Israel.”

Indeed, today’s Zionists often view Israel not as a modern state, but as the rebirth of ancient sovereignty. And yet, this view is not absolutely historically accurate, either. While artifacts certainly substantiate the existence of a Jewish presence in ancient Israel, this view projects a modern nationalist movement onto a historical period that predates nationalism by four millennia.

And just as Abbas’s comments hurt the chances of negotiations, the Jewish narrative is also hurting both Israelis and Palestinians alike.

For it’s not as simple as saying that Jews lived in Israel in ancient times, therefore the land belongs to the modern Jewish state. Zionism successfully activated anticipatory claims embedded in Jewish tradition, yet it is nevertheless very much a modern nationalist movement.

This move is hardly unique to Zionism. Nationalist movements often stake their legitimacy on claims to antiquity; it’s a trope academic historians call “primordialism”. The primordialist piece of a nationalist ideology posits modern nation states as a means to realize the rights of ancient peoples, which they creatively imagine and project into the past. Think, for example, of the French Revolution, a pivotal event in the emergence of modern nationalism. At the time of the Revolution, only about half of the subjects of the French monarchy spoke French, which surely calls into question the antiquity of a unified French identity. Nevertheless, this was central to revolutionary rhetoric.

Zionism as a Jewish nationalist movement certainly deploys the primorialist trope. And yet, here’s where it’s unique. Other nationalist movements employ primordialist fictions, where Jewish history features an actual, unique continuity with an ancient identity. Jewish religious, ritual and cultural history has always depended on its persistent connection to the Land of Israel; the Jewish ritual calendar corresponds to its agricultural calendar. As such, diaspora Jews frequently observe both Passover, the spring festival, and Sukkot, the autumn festival, knee-deep in snow. The foundational texts of rabbinic Judaism focus a great deal of energy on civil law addressing situations proper to the traditional occupations of the Land of Israel and commandments that can only be performed within its confines. We orient our bodies toward Jerusalem in prayer and sing of restoration at our weddings.

Furthermore, Jews have maintained a continuous presence in the land since antiquity, with sporadic attempts to rebuild a larger communal presence. The diversity of Jewish customs and theologies developed in the context of minority communities striving to survive in lands they perceived ultimately as foreign, ever conscious of a once and future home on the eastern edge of the Mediterranean.

Nonetheless, Zionism’s politicizing reinterpretation of the traditional Jewish connection to the land could not have occurred without the emergence of the nation state, an unmistakably modern political unit. In contrast to their antecedents, nation states link identity and territory tightly together. Where pre-modern monarchs often traded territory as part of marriage agreements without popular opposition, modern nationalist leaders cede territory very rarely, and generally face intense popular opposition when they do. Israelis who oppose relinquishing territory are often motivated, like Gabbay, by the application of a modern view of national territory to a biblical map. Yet although that map is ancient, sources are not in complete agreement regarding its boundaries, such that Talmudic sages debated precisely where Jews were obligated to observe the commandments specific to the land.

Additionally, where modern nationalisms construct broad, unifying, popular identities, readers of the Bible, Josephus, and rabbinic literature know that ancient political consolidations often failed this test. In the Bible, tribal identities often take precedence over Israelite identity. Depictions of the kingdom of Saul, David, and Solomon read less as a unified state than a brief imperial domination of tribal territories followed by division into two competing monarchies. Their kings, far from being natural allies, often joined with non-Israelite powers against one another. And ancient texts do not reveal much about the degree to which their subjects identified with one another across tribal identities and allegiances to different kings.

Parsing the Zionist movement’s continuities and discontinuities with the ancient past is not only an academic endeavor. It has real world consequences. For when more than one national community lays claim to the same piece of land, primordialism inevitably drives conflict, always privileging what is earlier and older.

Since the movement’s inception, Zionists have claimed to be the land’s original owners, often regarding non-Jewish inhabitants simply as generic Arabs with no distinct, rooted identity. This enabled early Zionists to explore “transferring” non-Jews elsewhere. The Central Zionist Archives contains a 1931 proposal from the Zionist Office for Arab Affairs, headed by Labor Zionist Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, who would later become Israel’s second president, to relocate Palestinians to Iraq as agricultural laborers under King Faisal. Absurdly, a socialist sought to dispossess workers and force them into foreign servitude under an autocrat propped up by imperial powers.

In 1948, primordialism influenced Ben Gurion’s refusal to allow 700,000 Palestinians, mostly non-combatants, to return home. The assumption that their identity was recent and weak is reflected in a disputed quote, that “the old will die and the young will forget.” While this may or may not capture Ben Gurion’s personal attitude, it definitely expresses how many viewed the decision at the time, justifying as short-term violence the mass dispossession that was necessary for the [re]establishment of a Jewish majority state. On June 16, 1969, over twenty years later, Ben Gurion’s protégé Golda Meir still maintained in the Washington Post: “There were no such thing as Palestinians.”

Zionist primordialism also plays an impeding role in the stalled peace process, preventing Palestinians from recognizing a Jewish nationhood that erases their own, the very recognition that Zionists believe is necessary to resolve the conflict. In response, like Abu Bakr, Palestinians often reduce Jewishness to a religion and deny any connection between contemporary Jews and ancient Israel and assert competing Palestinian claims to being Canaanites and Jebusites and ancient Israel’s true heirs.

In a perfect demonstration of how primordialism inevitably leads to chronological competition, PA President Mahmoud Abbas related in a 2011 speech how he responded to PM Netanyahu when the latter “claimed the Jews have a historical right dating back to 3000 years BCE.” Abbas claims to have told Netanyahu that “the nation of Palestine upon the land of Canaan had a 7,000-year history.” He went on to tell Israel’s Prime Minister, “Netanyahu, you are incidental in history. We are the people of history. We are the owners of history.”

Zionist primordialism provokes Palestinian primordialism, which then provokes Zionist attacks on the integrity of Palestinian history and identity, and vice versa, in a violent feedback loop of mutual denial.

Understanding both Zionism’s continuities and discontinuities need not entail the abdication of Jewish historical ties to the Land of Israel. Rather, it would enable a more productive engagement with the other people who share our mutual homeland. As Professor Joshua Shanes put it, “All nationalisms are modern constructions, but the building blocks are often quite real.”

Ori Weisberg is a writer, translator, and editor in Jerusalem. He holds a PhD in English from the University of Michigan and has lectured at American and Israeli universities.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO