Why Benjamin Netanyahu’s Outrageous ‘Ethnic Cleansing’ Claim Is Actually Clever Political Ploy

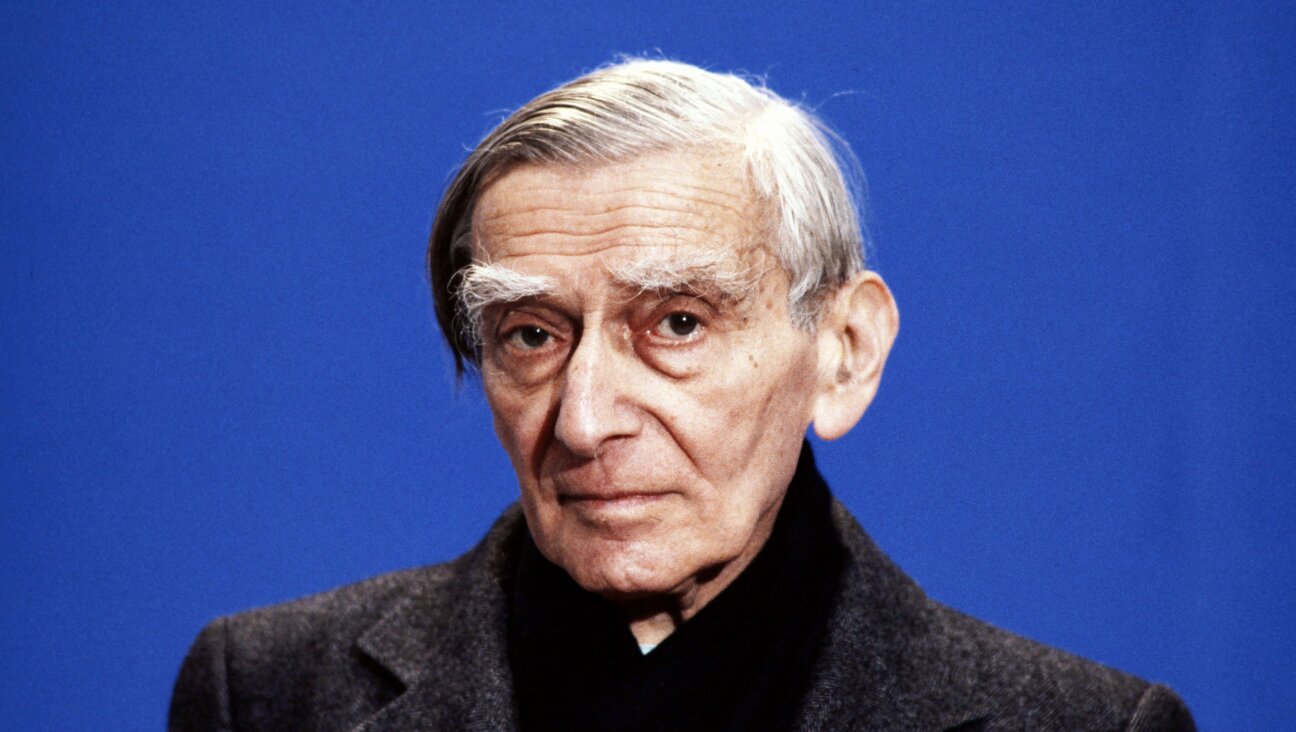

Image by Getty Images

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu managed to raise the collective blood pressure of official Washington to dangerous levels on September 9, charging in an online video that evacuating Israeli West Bank settlers, as Palestinians demand, would amount to “ethnic cleansing.” What’s more, he said, “some otherwise enlightened countries even promote this outrage.”

Obama administration officials were certain he was talking about them, and they weren’t happy. State Department spokeswoman Elizabeth Trudeau, in an unusually harsh retort, said Netanyahu’s words were “inappropriate and unhelpful.”

But while the prime minister may have been talking about President Obama and his team, he wasn’t necessarily talking to them. Most Israeli commentators said Netanyahu’s words were actually aimed at placating his own right-wing base, which has been flirting lately with rival parties further to the right.

The term “ethnic cleansing” is relatively new, coined during the Bosnia conflict in the 1990s. It refers to the deliberate removal of an ethnic minority population from a particular territory, whether by expulsion or mass murder. It’s often used as a euphemism for genocide, meant to evoke images of the Holocaust.

Netanyahu’s choice of words shouldn’t surprise us. Holocaust imagery is a staple of Israeli rhetoric, from Abba Eban’s 1967 “Auschwitz borders” speech to Netanyahu’s countless warnings about Iran. The practice is typically meant to evoke sympathy, but it often boomerangs. It energizes pro-Israel hardliners watching from the sidelines, but it usually stirs resentment among the main targets, Western moderates who support Israel but don’t like being called Nazis.

This time, though, those hardliners on the sidelines may actually have been the intended audience, not Washington. Consider the timing. There’s no reason for Netanyahu to tweak the Obama administration over settlements right now. On the contrary, the prime minister should be figuring how to stay on the president’s good side. The United Nations Security Council is likely to take up a French-backed resolution in November calling for a Palestinian state along the pre-1967 borders. That would severely undercut Israel’s future bargaining power. Israel is counting on Obama to veto it. This is no time to insult him.

On the Israeli domestic front, on the other hand, the “ethnic cleansing” message couldn’t be more timely. A poll released on Israel’s Channel 2 Television on September 6, three days before the prime minister’s video went up on Facebook, showed that if elections were held today, Netanyahu’s Likud party would fall behind Yair Lapid’s opposition Yesh Atid for the first time. Likud would drop to 22 Knesset seats from its current 30. Yesh Atid would jump to 24 from its current 11.

The Likud’s lost seats would go to parties to its right, Jewish Home and Yisrael Beiteinu. Lapid’s gains would come mostly from the Labor-led Zionist Union. The overall breakdown between right-wing and left-wing parties would hardly change.

Coming in first wouldn’t necessarily guarantee Lapid the prime ministership. He might end up in a rerun of the 2009 election. Tzipi Livni’s Kadima outpolled Netanyahu’s Likud that year, but she couldn’t convince a majority of Knesset members to join her in a coalition. Instead, second-place Netanyahu assembled a coalition and took over. The outcome of the next Knesset elections — which aren’t due until 2019, but could come sooner — might again make it impossible for anyone but Netanyahu to rule. Still, bad polls are worrisome.

It gets worse. Another poll, publicly released on Channel 1 on September 9, just hours after Netanyahu posted his video, showed Lapid winning 27 Knesset seats to Netanyahu’s 23. The overall breakdown in this poll showed a slight shift to the left, giving Lapid an even chance of assembling a coalition.

All in all, it’s the perfect time for Netanyahu to release a fire-breathing right-wing video message, to stanch the bleeding.

Beyond administration officials and Israeli voters, there’s a third possible audience for the video: the Palestinians. Over the last few weeks Vladimir Putin has been pushing to host a meeting in Moscow in the coming months between Netanyahu and Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas. Both sides have accepted in principle.

Given the pressures Netanyahu is sure to face for substantial concessions if talks get rolling, this would be a sensible time to start laying down markers, setting out his bargaining positions.

Netanyahu publicly proposed in January 2014, during Secretary of State John Kerry’s failed diplomatic shuttle, that Israeli settlers be allowed to remain as residents of a Palestinian state after Israel withdraws. He knew it was a nonstarter, but saying it let him continue nodding toward Palestinian statehood while assuring settlers they won’t be harmed. Opposition to the idea came mainly from two groups: settlers and Palestinians.

The settlers’ objection is that they settled the West Bank to ensure Israeli sovereignty, not to live under Palestinian rule. Naftali Bennett of the settler-backed Jewish Home party called the idea “unethical.”

Palestinians, for their part, say the settlements were created in violation of international law and must be dismantled as part of an Israeli withdrawal. They insist that a sovereign Palestine should be able to control its own immigration and citizenship rules.

In fact, the idea had been circulating long before Netanyahu injected it into the Kerry talks. It was reportedly raised back in 2008 by a top Palestinian negotiator, Ahmed Qurei, in his talks with Israel’s then-foreign minister Tzipi Livni. Livni rejected it as unrealistic.

Abbas flatly dismissed the idea at the outset of the Kerry talks in July 2013, months before Netanyahu embraced it. “In a final resolution, we would not see the presence of a single Israeli — civilian or soldier — on our lands,” he told a Cairo press briefing.

Statements like that — Abbas wasn’t the first to say it — have given rise to the Israeli complaint that the Palestinians want an ethnically cleansed, “judenrein” state.

Palestinians repeatedly insist that the Israeli accusation twists their position. “Any person, be he Jewish, Christian or Buddhist, will have the right to apply for Palestinian citizenship,” Palestine Liberation Organization spokeswoman Hanan Ashrawi told The Times of Israel in 2014. “Our basic law prohibits discrimination based on race or ethnicity.”

But, she added, Palestinians would not accept the presence of “extraterritorial Jewish enclaves” whose residents remained Israeli citizens, under Israeli protection.

Privately, Palestinians and Israelis alike call the idea of settlers remaining in a Palestinian state a recipe for disaster. Given Israel’s inability to control its own settler militants, and considering that most settlers reject the very idea of Palestinian statehood, leaving settlers under Palestinian rule would likely be a source of constant friction or worse, opponents say.

Considering all the facts, it’s tempting to call Netanyahu’s talk of ethnic cleansing an inflammatory distraction, if not downright dishonest. On the other hand, in a century-old conflict where defensive wars are labeled “genocide” and suicide bombers are hailed as freedom fighters, inflated rhetoric is small stuff. Obama will get over it.

Besides, when did we start expecting honesty in diplomacy, much less politics?

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO