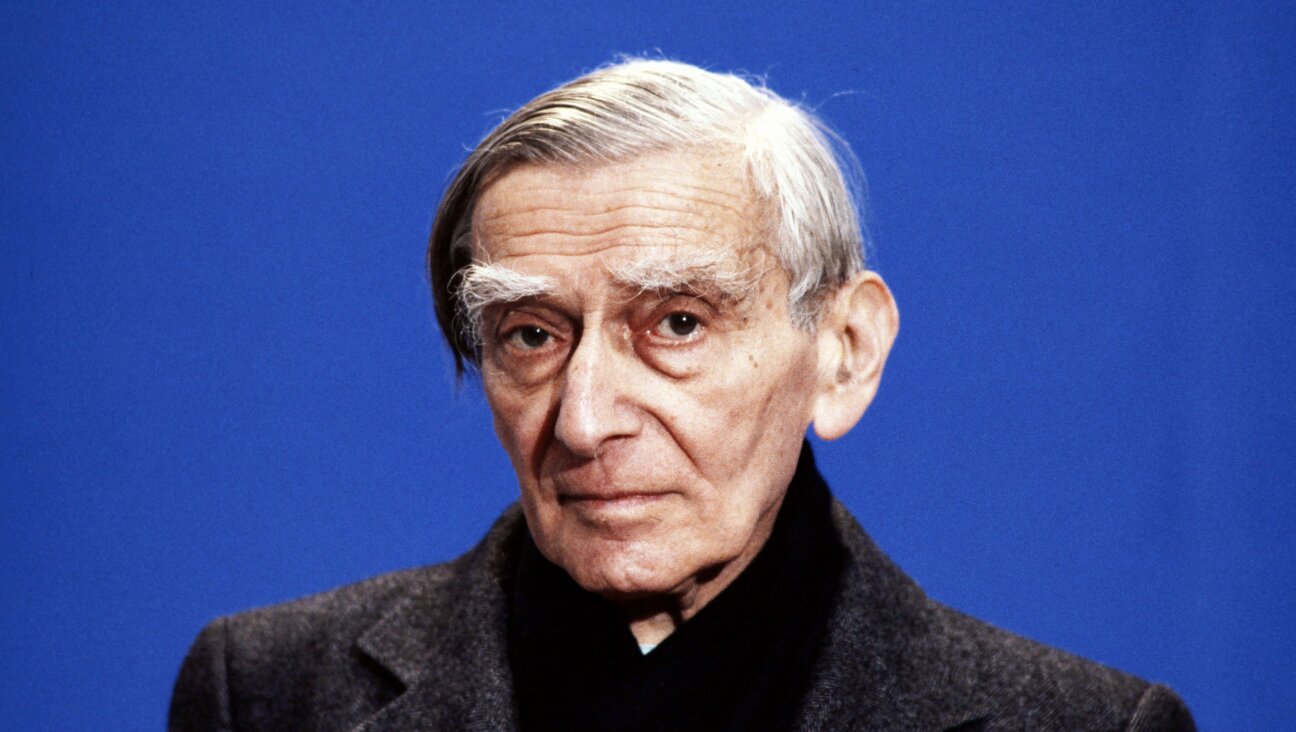

Why Avigdor Lieberman Might Just Be the Key to Mideast Peace. Really.

Image by Getty Images

It could turn out to be the biggest surprise of the year in Middle East diplomacy: Avigdor Lieberman, Israel’s blustering, ultra-nationalist new defense minister, just might be the key to reviving the moribund Israeli-Palestinian peace process. So, at least, say several key sources familiar with a complex round of behind-the-scenes Israeli-Arab contacts.

Lieberman’s significance lies in the fact that despite his fearsome reputation as an anti-Arab provocateur and bigot, he’s not opposed in principle to Israel yielding significant parts of the West Bank and allowing a Palestinian state. That’s a critical difference between him and the other top rightist in Benjamin Netanyahu’s coalition, education minister Naftali Bennett of the Orthodox-led, settler-backed Jewish Home party.

By positioning Lieberman on his right flank, Netanyahu could weaken Bennett’s veto power over compromises he might decide to make. Of course, much more will be needed to renew peace talks, including some tough Palestinian decisions. But recruiting Lieberman to the cause of peace could be an important first step.

It’s true that Israeli-Palestinian peace remains a distant hope at best. Trust between Netanyahu and Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas is virtually nonexistent. “They don’t like each other,” former State Department aide Ilan Goldenberg said. “And both are very risk-averse.”

Negotiators appear to expect few results right now, beyond agreement — if that — on interim measures that might keep the path clear for more substantive talks down the road.

What’s created the current possibility of a breakthrough, however slight, is a new initiative by the Egyptian president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Sisi unveiled it in a May 17 speech urging Israel and the Palestinians to resolve their own internal differences and return to the negotiating table, and offering Egyptian assistance. Significantly, the speech got warm responses from Israel, the Palestinian Authority and even Hamas, though each with different spins.

Sisi’s initiative grows out of two earlier initiatives begun quietly in the past two years. One was Sisi’s own, self-interested effort to bring together Israel and the Palestinians by changing their internal dynamics. Beginning in late 2014, after he’d successfully brokered a cease-fire in that summer’s Gaza war, he tried to reconcile the squabbling factions vying to succeed Abbas within his Fatah party. Next he aimed for a Fatah-Hamas reconciliation, hoping to restore Gaza to Fatah control, followed by Israeli-Palestinian peace talks. By mid-2015 all three reconciliation bids — Fatah-Fatah, Fatah-Hamas and Palestinian-Israeli — had failed.

The other initiative was by the former British prime minister Tony Blair, who began a new round of shuttle diplomacy in late 2015. Blair had retired in May 2015 after eight years as special envoy of the Middle East Quartet, the diplomatic alliance of Washington, Moscow, the European Union and the United Nations. After retiring he was approached by an Israeli lawyer named Yitzhak Molcho, a close confidant of Netanyahu who proposed a new effort outside the Quartet framework.

“Netanyahu was worried that President Obama was planning to work with the Europeans after the November elections, and he wanted to pre-empt it,” said Nimrod Novik, a veteran Israeli back-channel negotiator who has participated in some aspects of the current talks. Many in Jerusalem suspect that Obama will join with France in the fall to push for a U.N. Security Council resolution dictating Israeli-Palestinian peace terms.

Blair concluded after several shuttle rounds that the keys to forward movement were twofold. First, Sisi, the one Arab leader with clout and credibility on both sides, had to re-engage. Moreover, Sisi needed Saudi backing to offer Israel certain concessions.

Second, Netanyahu had to bring Zionist Union leader Isaac Herzog on board to create an Israeli government capable of flexibility.

Netanyahu had his own reasons for wooing Herzog, mainly to broaden his government’s fragile, one-vote parliamentary majority. But they had trouble agreeing on the scope of Herzog’s mandate to pursue peace negotiations. Moreover, Herzog faced stiff resistance within his own 24-member caucus. Most opposed joining a Netanyahu government on any terms.

In early May, with time running out before the Knesset’s summer recess, Blair urged Sisi to deliver a speech. Sisi demanded that Netanyahu first agree to respond to the speech with a public embrace of the Arab Peace Initiative. The 2002 Arab League resolution offered Israel full peace and normal relations with all Arab states in return for Palestinian statehood along the pre-1967 armistice lines, and a “just” and “agreed” solution to the Palestinian refugee problem. Israel had never responded.

Netanyahu had a demand of his own: commitment to a multilateral Israeli-Arab meeting, before any formal peace talks, to discuss Israel’s reservations about the initiative. Israel wants to clear up the vague but threatening-sounding language on refugees. It also wants to spell out a 2013 Arab League offer to modify the 1967 borders with land swaps. Most important, Israel rejects a requirement that it return the Golan Heights to Syria.

Sisi got a green light from the Saudis for the multilateral meeting. Netanyahu agreed to issue a qualified endorsement. On May 17, Sisi delivered the speech.

Then, on May 18, all hell broke loose. Netanyahu’s talks with Herzog collapsed, and a new partnership was announced with arch-hawk Lieberman. Voices around the world and across the Israeli spectrum denounced Lieberman for his lack of military expertise, his racist bombast, his attacks on civil liberties and his theatrical threats against Israeli Arabs, Palestinian leaders and even Egypt.

Sisi was said to be furious at the unexpected turnabout. His peace initiative was widely described as all but dead.

Two weeks later, the picture looked very different. Netanyahu issued his qualified endorsement of the Arab Peace Initiative as promised. Lieberman gave his own endorsement, saying the initiative “has some very, very positive elements that enable a serious dialogue with all our neighbors in the region.”

Lieberman also voiced “strong commitment to peace” and to a “final status agreement” with the Palestinians, reversing his long-standing, outspoken skepticism. He even acknowledged his notorious penchant for verbal violence, joking that since joining the Cabinet, he’d “undergone surgery to lengthen my fuse.”

Equally important, Netanyahu has continued working to bring Herzog on board, while Bennett threatens to quit over the embrace of the Arab peace plan. The pieces are, surprisingly, falling into place for a renewed peace drive.

Can Netanyahu stick to the script, close the deal with Herzog and begin making hard decisions that negotiations require? That remains to be seen. Over 20 years he has earned his reputation for breaking promises. On the other hand, his new partner, Lieberman, is almost frighteningly consistent. He does what he says he will, for good or ill. Negotiators are hoping that if Netanyahu promises to show up for peace talks, Lieberman will see he gets there.

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter @JJ_Goldberg

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO