The 2 Options Left for Conservative Judaism

Image by JTS

(JTA) — The Conservative movement was once the very embodiment of what it meant to be an “American Jew.”

As the 130th anniversary of the founding of its flagship Jewish Theological Seminary approaches in 2016, the centrist movement that historically straddled the polarities of Reform and Orthodox is struggling to maintain its identity and attract new followers. The movement’s congregational arm recently hired branding consultants to provide it with a clearer identity.

As one who was raised as a Conservative Jew, I believe there are only two realistic choices for the movement. One option is to acknowledge that it has become virtually indistinguishable from Reform Judaism and the two denominations could merge their institutional structures. The other option is to carve out a much narrower middle ground catering to the smaller group of Conservative Jews seriously committed to observing Jewish law but in an egalitarian worship framework.

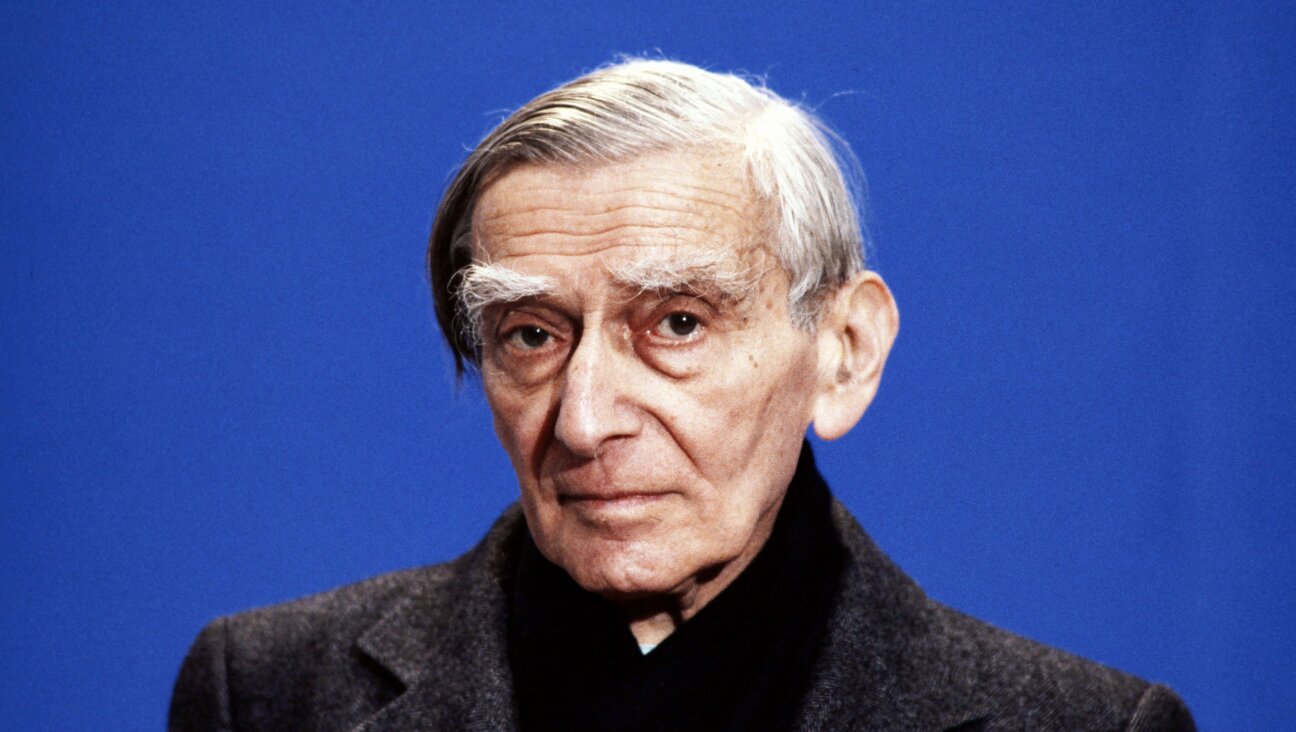

The ideological roots of Conservative Judaism date back to Europe in the mid-19th century, but the denomination was defined by Solomon Schechter, who served as president of the Jewish Theological Seminary from 1902 to 1915. The Conservative movement clung to rituals far more tightly than did the Reform movement, which was characterized in those days by a pronounced rejection of Jewish law and tradition. But compared to Orthodoxy, Conservative Judaism was more liberal in practice and ideology.

For many years, Conservative Judaism’s middle-of-the-road message was a very good fit for the majority of American Jews. By the 1940s the movement boasted the largest number of affiliated families.

What changed?

Sociologist Samuel Heilman has documented the growth and strength of Orthodox Judaism beginning in the later decades of the 20th century. Meanwhile, many Reform synagogues have manifested a return to tradition, embracing once-discarded practices such as Hebrew prayer, the celebration of life cycle events, and the wearing of kippahs and prayer shawls. In contrast, many of the Jewish law opinions of the Conservative movement have become more liberal on certain issues, further blurring some lines between Conservative and Reform Judaism. Natural attrition and an increasing number of unaffiliated Jews also have taken a toll. All of these factors have resulted in a one-third drop in Conservative movement affiliation over the past 25 years.

Visit most Conservative synagogues on a Saturday morning when there is not a bar or bat mitzvah and likely you will find mostly an older crowd. Where are the children of Conservative Jewish baby boomers? According to sociologists of American Judaism as well as anecdotal evidence, the really serious ones often migrate to modern Orthodoxy or attend independent prayer groups (minyans) that lack an official denomination. Many of the others put their Judaism “on hold” until they have a family, at which point many find Reform a better option for a variety of reasons — not the least of which is intermarriage. Since Conservative rabbis still are prohibited from performing such marriages, Reform becomes an easy choice for these couples. The 2013 Pew Report on the American Jewish community found that 30 percent of Jews raised Conservative have become Reform.

A merger between the Conservative and Reform movements is more than a theoretical possibility. Surveys over the past 15 years show that although Conservative Jews still exhibit higher degrees of traditional observance than their Reform counterparts, a growing number of Conservative and Reform Jews agree on hot-button social issues such as interfaith and same-sex marriage, as well as the determination of Jewish status based on either parent rather than only the mother. A formal union between the movements could afford a majority of the American Jewish community a greater sense of unity as a result of one governing institutional structure rather than two.

The alternative is for the Conservative movement to narrow its audience by refining its mission. A tribute to Conservative Judaism is that it has produced a core group of Jews whose daily lives revolve around Jewish law in a way closer to modern Orthodox Jews but who insist on an egalitarian worship community. By contrast, the Rabbinical Council of America, the largest organization of Orthodox rabbis, last month issued a resolution banning its members from hiring a growing number of Orthodox women who are being groomed as clergy.

Given that the center of Orthodoxy has moved further to the right over the years, it is highly unlikely that these views concerning female participation will change anytime soon. This reality opens the door for a slimmer but more cohesive Conservative movement that potentially could draw members from pockets of modern Orthodoxy as well the proliferating independent minyans sharing these practices. According to a national survey conducted in 2007, nearly half of those who attend independent minyans grew up in Conservative synagogues and another 20 percent in Orthodox synagogues. This group alone provides a solid target audience for a refined Conservative movement.

This second alternative will face obstacles. It probably will further shrink the movement; this will have financial consequences. It will depend on rabbis who are willing to set and demand higher religious norms with respect to all areas of Jewish observance. But the payoff is that it would provide a viable and distinct identity for the denomination.

The easiest route for the Conservative movement is to make cosmetic changes to its big tent brand and hope that better marketing will bring in more numbers, but this goal does not seem realistic. Neither does a merger with Reform just yet.

I would urge the movement to reclaim Solomon Schechter’s mission of “conserving” the Jewish tradition by focusing on its strongly observant but egalitarian constituents. This path will allow the movement to preserve a unique legacy.

Roberta Rosenthal Kwall is the Raymond P. Niro Professor at the DePaul University College of Law. She is the author of “The Myth of the Cultural Jew: Culture and Law in Jewish Tradition” from Oxford University Press, 2015.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO