Bibi’s Cabinet Rattled as Key Livni Ally Quits

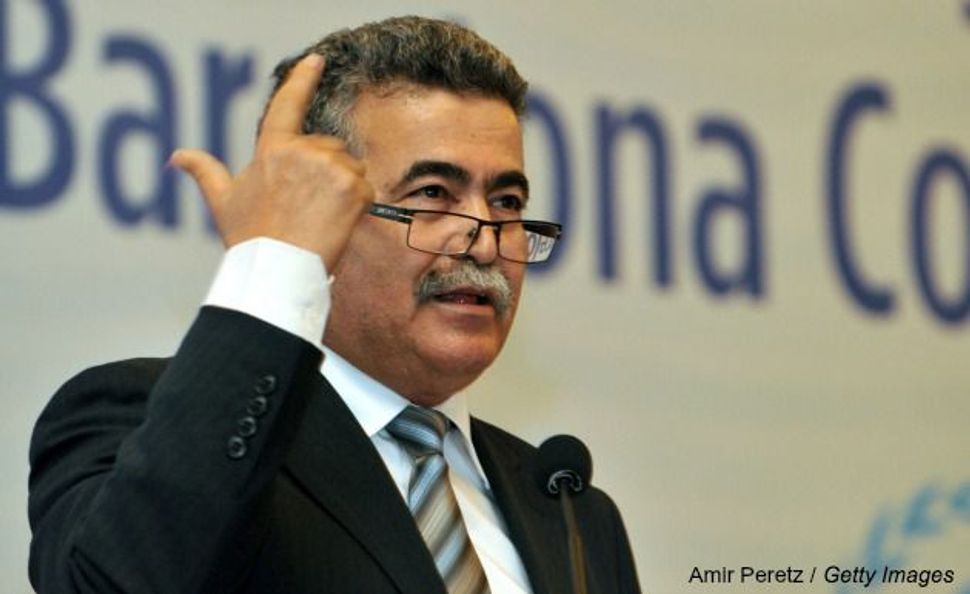

The Moroccan-born Amir Peretz could serve as Israel’s first Mizrahi prime minister. Image by Getty Images

The Netanyahu government’s most left-wing member, environmental defense minister Amir Peretz, quit the cabinet on Sunday and declared war on the prime minister, vowing to work for a new government committed to peace and economic justice. Peretz, a onetime Labor Party chairman and defense minister, is a member of Tzipi Livni’s Hatnuah party.

The move comes amid growing signs of internal weakness in Netanyahu’s coalition. Just a week earlier Netanyahu accepted the resignation of interior minister Gideon Saar, a popular Likud rising star who’s long been considered a possible successor to Netanyahu. He’s now expected to emerge as a rival.

And on Thursday Netanyahu came under an attack of unprecedented fury from a senior coalition ally, Jewish Home leader Naftali Bennett. In a speech at Bar-Ilan University Bennett declared that a “government that hides behind concrete barricades has no right to exist.” Deriding static defense tools like the Iron Dome missile defense as well as the separation barrier, Bennett called for the government to respond to the current wave of Palestinian violence with a new “Operation Defensive Shield,” referring to the massive military assault against Palestinian population centers in 2002 that broke the back of the Second Intifada.

All three moves come against a backdrop of escalating Palestinian violence that’s stirring fears of a third intifada, and the growing likelihood of new elections next spring, two years ahead of schedule.

Of the three defections, Peretz’s is of the least immediate consequence to Netanyahu, but it could have the strongest long-term impact. Saar announced his resignation in September, saying he planned to take a break from politics to spend more time with his family. Rumors abound, though, that he’ll join forces before the next election with another former Likud up-and-comer, onetime social welfare minister Moshe Kahlon (kach-LONE), who retired from politics before the 2013 elections but announced plans this year to form a “new political framework.” Kahlon soared to stardom after winning the top spot after Bibi in the 2006 Likud primaries. Saar did the same thing in 2008.

Polls have shown Kahlon winning 10 to 11 Knesset seats, mostly at the expense of Shas — because of his Sephardic working-class background — and Yesh Atid, with its middle-class economic message. That’s not enough to challenge Netanyahu’s leadership, either in the Likud or with the electorate, but it would almost certainly make him a senior partner in any future Netanyahu coalition.

As for Bennett, he’s been maneuvering for months to establish himself as the leader of the hardline right. His Bar-Ilan speech was just the latest salvo in that campaign. On Sunday ministers from Bennett’s Jewish Home party joined with ministers from the Likud and its erstwhile partner, Yisrael Beiteinu, to give committee approval to a bill that would apply Israeli civilian law to Israeli settlements in the West Bank. At present settlements are under the authority of the military, which governs the territory under the rules of occupation. Extending civilian law to occupied territory was the measure Israel took in 1967 and 1980 that effectively annexed East Jerusalem and in 1981 to annex the Golan Heights.

If the measure makes it to the Knesset, it will add pressure on Netanyahu as he struggles to hold onto his right flank while trying to preserve some credibility with the international community.

Peretz represents a different sort of threat to Netanyahu. Short term, his resignation was intended to free him of ministerial responsibility and allow him to vote against the state budget that was to be presented to the Knesset today for the first of its three readings. In the intermediate term it puts pressure on Livni, who’s built her political identity as a champion of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process but now serves in a government that has effectively abandoned the process.

Emblematic of the bind she’s in is her choice of a new environment minister to replace Peretz. The natural candidate to take Hatnuah’s second cabinet seat is the No. 2 on her list, Amram Mitzna, another former Labor chairman. But Mitzna has been even more critical than Peretz of Bibi’s Palestinian policies, and couldn’t join a cabinet that Peretz declared himself unable to sit in. The ministry will likely go to No. 4 on Livni’s six-member list, ex-Likudnik and onetime finance minister Meir Sheetrit. Environmental affairs, perhaps the least prestigious cabinet ministry, is a big step down for someone who narrowly lost the state presidency to Reuven Rivlin this summer, but he’ll take it.

Longer term, Peretz’s move seems to have put Netanyahu’s coalition in play by challenging the doves in both Hatnuah and Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid party. For Livni, the fact that her numbers 2 and 3 are halfway out the door (ditto her number 5, Elazar Stern a retired major general and outspoken Orthodox liberal) are a reminder of the implausibility of her political position as Netanyahu’s diplomatic fig-leaf.

As for Lapid, his top security expert, science minister and former Shin Bet chief Yaakov Peri, told Army Radio on Sunday, following Peretz’s resignation, that Netanyahu was “leaning increasingly to the right” and Yesh Atid “may have to make a decision regarding staying in the government.”

Both Livni and Lapid have been deterred from threatening to bolt by polls that show both of them getting battered in a new election — Livni would fall to two seats at best and Lapid would likely drop to nine or 10 from his current 19. There’s long been wistful talk on the left of forming an alternative government within the current Knesset, relying on Livni, Lapid, Yitzhak Herzog’s Labor Party and perhaps Meretz and Shas. But that would require Lapid to agree to sit with Shas, sacrificing his anti-Haredi agenda for the sake of peace. More challenging, it would require two of the three top figures, Livni, Lapid and Herzog, to swallow their pride and let the third take charge. So far that’s been elusive, to put it mildly. And nobody has emerged in the current Knesset — the law requires the prime minister to be a Knesset member — who could pull the rivals together.

Enter Amir Peretz. Once the meteoric star of the left, feisty dove, Moroccan-born ex-Histadrut head, lifelong resident of Sderot, his reputation was destroyed when he agreed to the ill-fitting position of defense minister in Ehud Olmert’s government in 2006, only to see the Lebanon War break out that summer and leave him looking helpless. He was defeated in a Labor leadership primary the following year, after only two years as party chief.

His reputation got a new lease on life this summer, though, thanks to Iron Dome, which he championed as defense minister and single-handedly forced through the system despite furious opposition from the military brass.

Since the summer, his diehard fans have been waiting to see if he could leverage the war to effect some sort of comeback. Judging by his fiery speech to a business conference on Monday (watch it here if you can follow Hebrew), he’s looking like someone who thinks his time has come. Whether his colleagues or the public will agree remains a very open question, but at minimum he’s gotten their attention.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO