The Raw Honesty of Klinghoffer

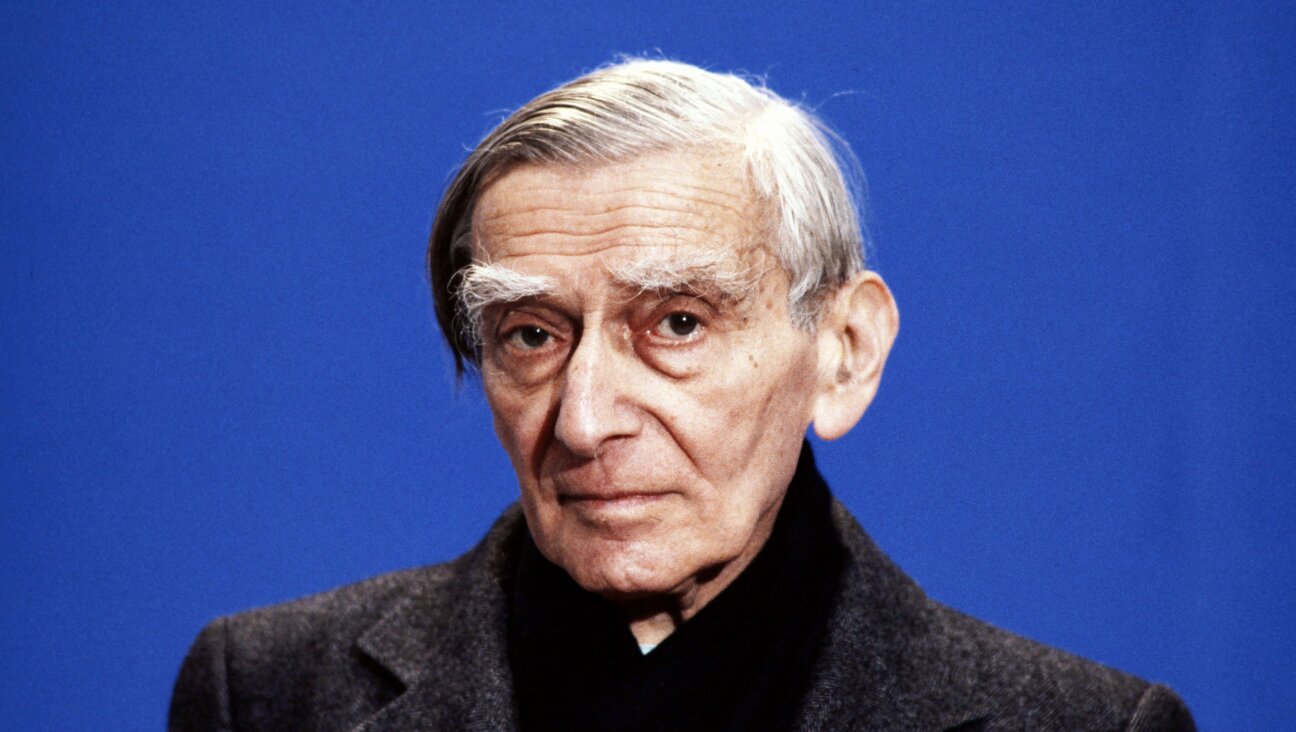

The Day Our Hope Dies: The opera takes the audience on a whiplash emotional journey. Image by KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA

“You’re enabling terrorism!” a woman said as I made my way through a maze of police barricades and a crowd of angry protestors chanting in front of Lincoln Center. A man standing next to her ostentatiously photographed ticket holders, as though documenting them in the act of committing a crime. Neither of them understood a word of the remarks I directed at them in Hebrew. They and dozens of others had come to protest the opening night performance of “The Death of Klinghoffer” at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, brandishing placards and handing out flyers that warned ominously of anti-Semitism and justification of terrorism.

My decision to spend $100 on a ticket for the opera was not a political act. In fact I was barely aware of the controversy leading up to Monday’s opening night, despite all the publicity it had attracted. I’d spent the spring and summer obsessively reading, writing and speaking about events in Israel-Palestine — the abductions, the murders, the riots, the riot police beatings and then the five-week war in Gaza. Until a week after the ceasefire, I was only peripherally aware of what was going on elsewhere in the world, let alone in my own city.

I went to the opera for the love of music, because a musician-composer-conductor friend asked if anyone wanted to accompany him, and attending performances of complex music with knowledgeable people makes the experience richer and more interesting.

Composed by John Adams (“Nixon in China”), “Klinghoffer” tells the story of a 1985 terrorist incident that occurred off the coast of Egypt, when four members of the Front for the Liberation of Palestine (FLP) hijacked a cruise ship named the Achille Lauro and murdered one of the passengers, a wheelchair-bound, 69 year-old Jewish-American man named Leon Klinghoffer. In a particularly brutal detail, the hijackers forced members of the ship’s crew to toss the dead man’s body overboard.

It’s a critically acclaimed opera, but has been staged only a few times since its 1991 premier because it elicits so much controversy. Protestors insist that the opera portrays the hijackers sympathetically, that it belittles the murder of Leon Klinghoffer and that it is anti-Semitic (even though Abraham Foxman of the ADL has said that he does not believe the opera is anti-Semitic). A message from Ilsa and Lisa Klinghoffer, the daughters of the murdered man, was included in the playbill. The opera, they write, “…rationalizes, romanticizes and legitimizes the terrorist murder of [their] father.”

Having seen the opera, I must respectfully disagree with the bereaved daughters. But I must also acknowledge that watching the opera is not the same as seeing it.

During the first act, for example, just after a gut wrenching scene that involves a child escaping from the grasp of one of the terrorists and running frantically to the safety of his crouching grandmother’s open arms, a man in the audience stood and shouted, at least a dozen times, “The murder of Klinghoffer will never be forgotten!” Turning to me, my companion remarked, “Isn’t not forgetting the murder the whole point of the scene we just watched?” Clearly, the man who tried to disrupt the performance had not seen, or had not understood, the scene that had just ended. He had come with an agenda to carry out, and that was all.

“The Death of Klinghoffer” does not offer false moral equivalencies. It does not romanticize the terrorists, either. It does present them as human beings rather than cartoon figures, but I simply do not see how anyone can come away with the impression that they are anything but human beings who committed a terrible act.

The raw honesty of the opera becomes apparent in the first act when Mamoud, one of the hijackers, sings a powerful, emotional aria that veers from sentimentality to narrative to personal tragedy. First he describes his fondness for late-night radio talk shows that are about lovers driven apart by circumstance, then his mother’s memory of their exile from Palestine in 1948 (“there was a raid / My uncle carried/me in his coat”), and finally the experience of seeing the corpse of his brother—who, along with his mother, was among those massacred at Sabra and Chatila in 1982.

“Almighty God,” sings Mamoud, “In His mercy showed / my decapitated / Brother to me / And in His mercy/Allowed me to close/My brother’s eyes / And wipe his face.”

The ship’s captain, who is alone on the stage with Mamoud, says in response, “I think if you could talk like this / Sitting among your enemies/Peace would come.”

But Mamoud makes it clear that he is not interested in peace. “The day that I / And my enemy/ Sit peacefully / Each putting his case /And working towards peace / That day our hope dies /And I shall die too.”

It’s a shocking exchange, underlined later when Klinghoffer, rising from his wheelchair, accuses the hijackers of being gratuitous killers motivated solely by anger and hate: “You don’t give a shit, / Excuse me, about / Your grandfather’s hut, / His sheep and his goat, / And the land he wore out. / You just want to see / People die.”

The opera takes the audience on a whiplash emotional journey, from sympathizing with Mamoud for his terrible losses, to despair laced with horror at seeing how the conflict’s very intractability lies in each peoples’ placing more value on their narratives than on peacemaking. That is why the opera opens with two choruses: The Chorus of the Exiled Palestinians; and The Chorus of the Exiled Jews. Each people’s historical narrative is presented from their perspective, without judgment. But then, as the opera unfolds and the actions committed by individuals in the name of their narratives are explored, we enter the area of ethical judgment. As in the scene where a Palestinian hijacker who scatters money taken from the pocket of a dead Jew, while making anti-Semitic comments. The audience is meant to be disgusted by this, and it is.

Watching this opera was a deeply emotional and thought provoking experience. The driving musical score and the set itself both played powerful roles in propelling the drama of the story. But the performances, including the one by the mute hijacker who is tasked with shooting Klinghoffer, are riveting. I can’t remember the last time I sat totally absorbed through an entire opera; my mind did not wander even once.

Those people protesting outside? I worry about them. And, by extension, I worry about what their actions say about the state of the Jewish community. What has happened to us? We are plagued by a terrible, paralyzing, anti-intellectual fear of art and critical discourse. The protestors, whether they had seen the opera or not (and I think most did not) are blind to the very obvious truth that the opera in fact proves their points about the evils of terrorism and the dubious motives of the hijackers.

Later that night, my companion, a non-Jew who was incensed by the controversy over staging a work of art, sent me a text message: “I feel more pro-Israel right now than I have in a long time. You can quote me on that.”

Lisa Goldman is the director of the Israel-Palestine Initiative at New America.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO