How Many Lives Is a Da Vinci Masterpiece Worth?

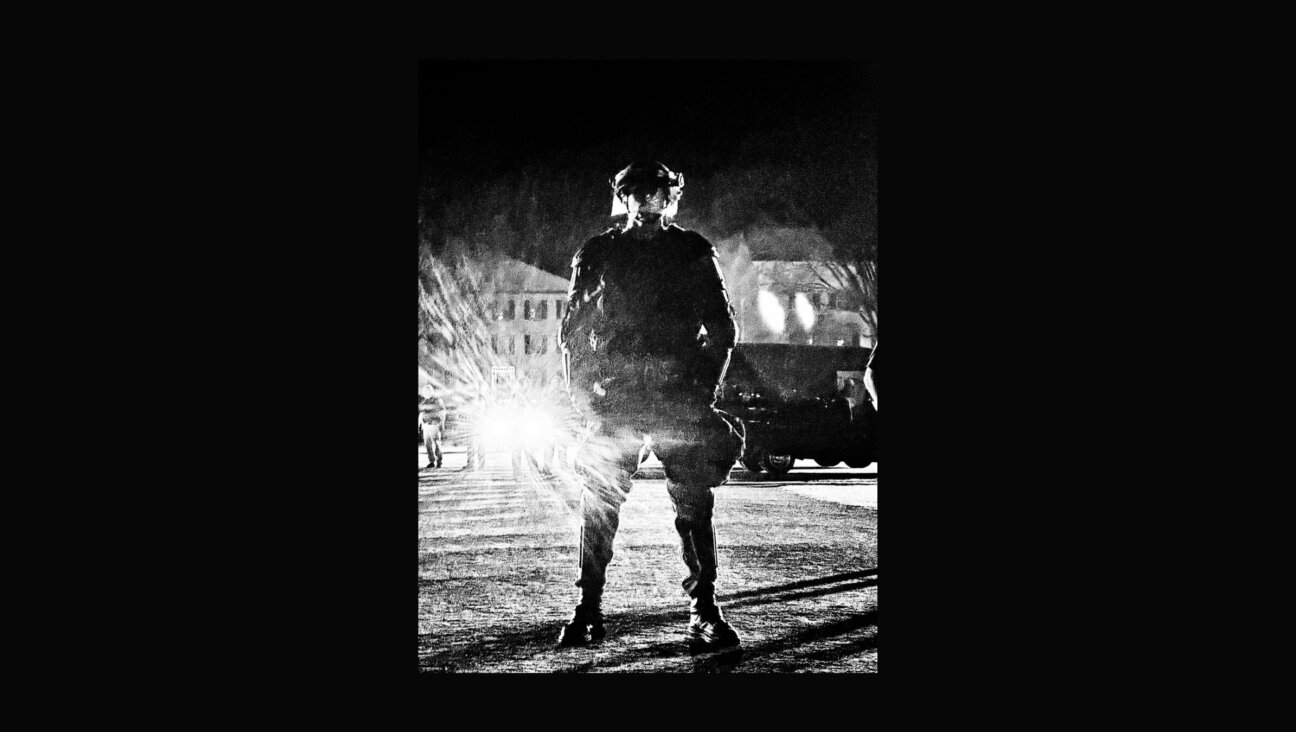

Saved: The real ?Monument Men? deliver Leonardo da Vinci?s ?Lady With an Ermine? to safety. Image by National Archives

George Clooney’s new film, “The Monuments Men,” is based on the real-life story of a team of scholars and artists who threw on some fatigues and dashed off to Europe during World War II to save imperiled art. Their mission is very explicitly framed as a heroic struggle to save Western Culture (with that capital “c”), “our way of life,” from the Germans and later the Russians. This was a battle as worthy as others fought during the war, a point driven home by a shot that juxtaposes a charred Picasso with a barrelful of gold-capped human teeth.

If that visual makes you a little queasy, then you will no doubt recoil from the fact that Franklin Roosevelt’s administration backed this culture-saving effort while failing to put equal resources into saving Jews.

The film, while not particularly successful as a piece of art itself, raises larger questions about the value of art and whether, and how, it can be measured against human life. Can we ever justify giving money to supporting arts and culture when we could be saving lives?

I imagine that most of us, should we have been sitting in the Oval Office during the war, believe that we would have sidelined the Picasso in favor of the humans to whom those gold-capped teeth belonged. But if we follow the thinking of the philosopher Peter Singer, the vast majority of us choose art and culture over life each day. I know I do.

Singer’s famous thought experiment on giving goes like this: You are on your way to work, and you notice a child drowning. Would you jump into the pond to help save him? Even if you ruined a nice pair of shoes? The answer is fairly obvious for anyone who is not a sociopath. But taken to the next level of abstraction, things get blurrier for most people. Any extra money spent on things like an unnecessary pair of shoes is akin to allowing a child to drown. For Singer, the $20 you might spend on a novel and your annual contribution to the local art museum are in the same category: money toward beauty and pleasure that could have been donated to an organization like Oxfam, which would have used it to save a child’s life.

In an op-ed in The New York Times published last August, Singer states, in no uncertain terms, that one should not give money to the arts. He draws up a hypothetical between giving money to an art museum with plans to build a new wing and giving money to an organization that prevents trachoma, a treatable infectious disease that causes blindness. Basically, if you support the new wing, you are responsible for people going blind.

That we could all sacrifice some of our luxuries to give money to those in need is a given. Americans currently rank 13th in charitable giving in the world, and with income inequality rising on a national and global scale, those of us closer to the top certainly could live with less in order to give more. So, fine, no more Tuesday night sushi, or iPhone upgrades. There’s at least $50 a month for trachoma. But does this also mean that we should refrain from supporting arts and culture, whether as consumers or as patrons? And what about the money we spend on religious objects?

Singer’s philosophy has a stark simplicity that makes it very appealing. There’s something attractive about the idea of relying on a rigid hierarchy of values to guide how we should behave in society and in the larger global community. Even if we don’t immediately sell our cars and donate the money to dying children, it is still difficult not to fiercely nod along to the idea that we really need to save that drowning child.

Though if we do follow Singer’s line of thinking, it leaves us with a vision of the world where art and culture, religious and otherwise, are subjugated by the imperative to save human lives. Sounds kind of bleak, right?

Part of the issue here is that Singer’s theory ignores culture’s capacity to create empathy and sensitivity. Unlike cell phones and sushi, culture can teach us about the subjectivity of our existence, and provide us with the tools we need to delve into the memories and myths — cultural and individual — with which we surround ourselves. These are the very things that inspire generosity, that allow us to recognize the humanity in others as we learn to see it within ourselves. That we often arrive at these realizations through the experience of pleasure and beauty does not discount their impact.

The problem with culture and the good it produces is that it is harder to quantify than, say, curing 1,000 cases of trachoma.

Still, Thomas Wartenberg, a philosophy professor at Mount Holyoke, says one could use the Singer line of thinking and come up with an opposite result. Singer is a utilitarian philosopher, which means he believes that ethical judgments are based on “the greatest happiness of the greatest number,” as the philosopher Jeremy Bentham put it.

“A great painting will be seen by many people over the course of many years. One could argue that, even if the increase in their well-being was not as dramatic as that of the difference between life and death, it might amount to a very significant increase in overall welfare,” Wartenberg told me.

“Cruel as it might seem, if we apply the utilitarian principle in an unbiased manner, it could turn out that it’s better to let a small number of people die in order to save a lot of artistic masterworks,” he said.

In the Talmud, there is a brief anecdote that is quite similar to Singer’s drowning child scenario. Tractate Sotah Folio 21b states: “What is a foolish pietist like? — e.g., a child drowning in the river, and he says: ‘Let me first remove my phylacteries.’ By the time he removed his phylacteries, the child has drowned.”

The obvious difference is that it is the trappings of religion, and not materialism, standing in the way of the rescue. Though the other and, in my opinion, more important distinction is that there is no expectation that this pious man will permanently abandon the practice of laying tefillin, not to mention buying the phylacteries, in favor of dedicating his life to teaching every child on the planet to swim — therefore preventing future drowning deaths. This isn’t a lesson privileging physical needs over spiritual or cultural ones, but instead a point that one can temporarily abandon religious responsibilities in order to save a human life.

Thanks to the Second Commandment, Jews don’t have much of a visual arts tradition to maintain, but this doesn’t mean that we have avoided the fetishization of symbolic, and expensive, objects altogether. From our extremely costly hand-calligraphed Torahs, to the dwellings that house our places of worship, to our individual Sabbath table settings, we’ve got our fair share of possessions that we prize.

When I asked my friend, Jewish text scholar Ruby Namdar, what he thought about Singer’s imperative, he said he far preferred the Jewish philosophy of giving, which, as many interpret today, calls for giving 10% of one’s annual income to charity. He also pointed out that Jewish scripture doesn’t call for the eradication of poverty, but instead just to alleviate the suffering.

“The idea that you will be totally selfless, and will resist bringing beauty into your own life through art and pleasure, that is just not applicable philosophy,” Namdar said. “The beauty of the Jewish way of thinking is that it doesn’t create a model that is impossible to live up to.”

Namdar reminded me of a line from “our anti-Semitic friend” Ezra Pound’s poem Canto 13: ““Anyone can run to excesses, / “It is easy to shoot past the mark, / “It is hard to stand firm in the middle.”

Though perhaps it takes someone like Singer, in all his excess, to remind us of the importance of giving in the first place.

Even if I can justify buying tickets to Twelfth Night or giving to the Met over donating to malaria research, I want to be aware of what I am really deciding between, and accepting the discomfort that difficult decisions like this might bring.

Elissa Strauss is a contributing editor to the Forward.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO