Yiddish 4.0

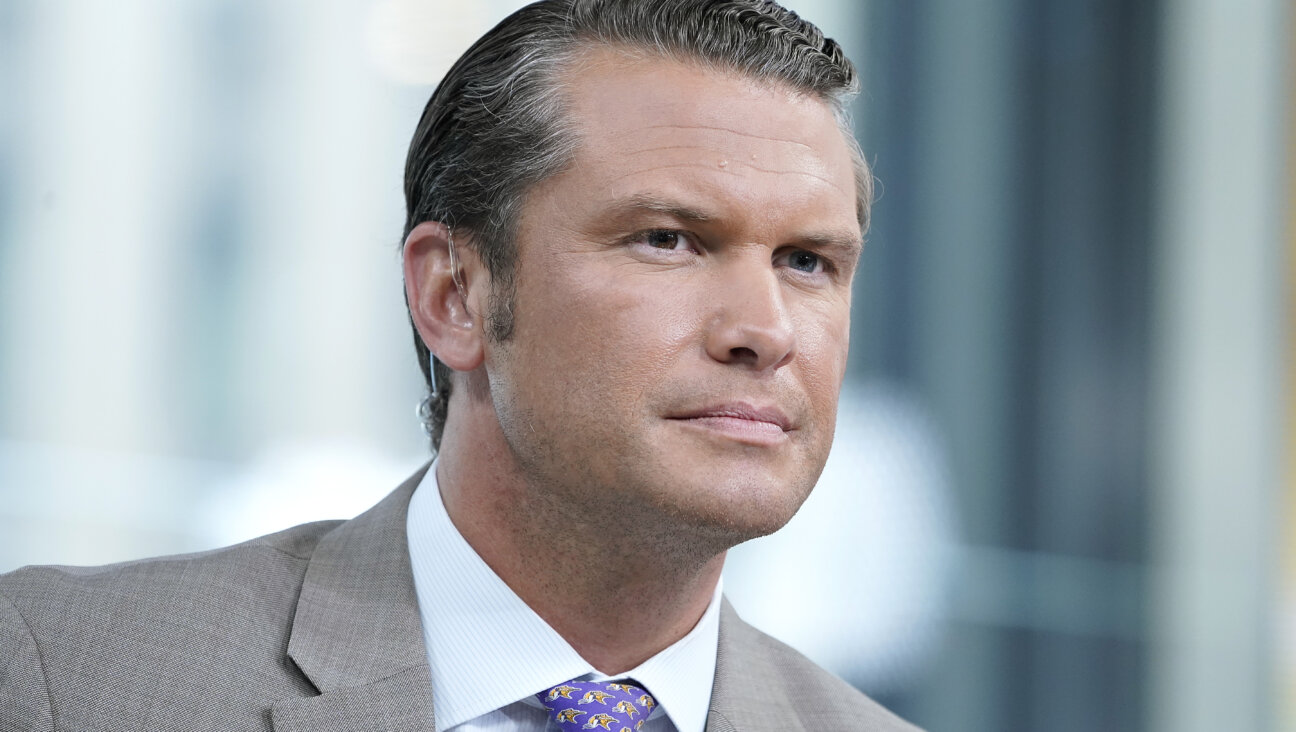

Boris Sandler Image by nate lavey

What mazel! Last week, Yiddishists round the world woke up to find an article by Joseph Berger about the Forverts — in the New York Times, no less — entitled: “For Yiddish A Fresh Presence Online”.

The next day, a Hebrew translation of the article appeared in the Israeli newspaper, Haaretz, with a slightly different headline: “Will Yiddish be Revived through the Internet?” Basically the same story, but with a more skeptical twist.

Reuters and the Columbia Journalism Review also published pieces about the new daily Forverts, which you can find online at yiddish.forward.com.

So what’s the big deal? After all, the Forverts has had a website since 1999. In fact, the Yiddish language has felt very much at home on the web for years, coining new terms for the electronic revolution (e.g. blitspost for email). Even Hasidic users have set up a haymish Yiddish-language community on the internet.

In other words, the virtual world has been hearing Yiddish for quite some time.

On the other hand, let’s enjoy this moment in the limelight — especially since discussions about Yiddish tend too often to veer towards eulogies. For the past 60 years, Yiddish writers have had to contend with the cliched question: “So how long do you think that Yiddish will survive?”

Often, these are the same people whose knowledge of Yiddish literature extends to just two or three writers, and their fluency in the language to roughly five or six words, like latkes, gefilte fish and … schmuck.

Unfortunately, even the erudite field of Yiddish literature isn’t immune from this pessimism. Most university courses date the era of Yiddish literature starting from the diaries of Glikl of Hamelin, a Jewish businesswoman who lived in the late seventeenth century, to the Holocaust, creating the impression that between the Holocaust and today there were, and are, no Yiddish writers.

Ignorance about Yiddish runs deep. The Reuters author defined Yiddish, for example, as “a vibrant German dialect peppered with Hebrew and Slavic words and written in Hebrew letters”.

And yet, this denigration of a language with a world-class literature has become the norm for many journalists, including those of Jewish publications. Even many Jewish intellectuals, experts in science, art, medicine, and leaders in Jewish organizational life, are sadly ignorant about their own national treasure.

Yiddish suffered terribly in the twentieth century, at the hands of our enemies as well as by many Jews (let’s not forget Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, who famously remarked that the Yiddish language “grates in my ears”). And yet, we are also graced by the deep appreciation of others, like Israel Prize-winning writer Aharon Appelfeld, who once told me, in fluent Yiddish, that he happily learned the language from two places in Israel: at Communist meetings, and by wandering the streets of the Hasidic neighborhood, Mea Shearim.

Hopefully, the virtual world of the 21st century will provide an easier path for Yiddish. We certainly hope to do our share, by providing the digital daily Forverts with fresh new articles, daily podcasts from Jewish communities round the world, educational and entertaining video programs, and much more — doing everything we can to ensure a bright future, just as our predecessors at the Forverts would have wanted us to do.

Boris Sandler is editor of the Forverts and yiddish.forward.com

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO