My Early Days with Ed Koch

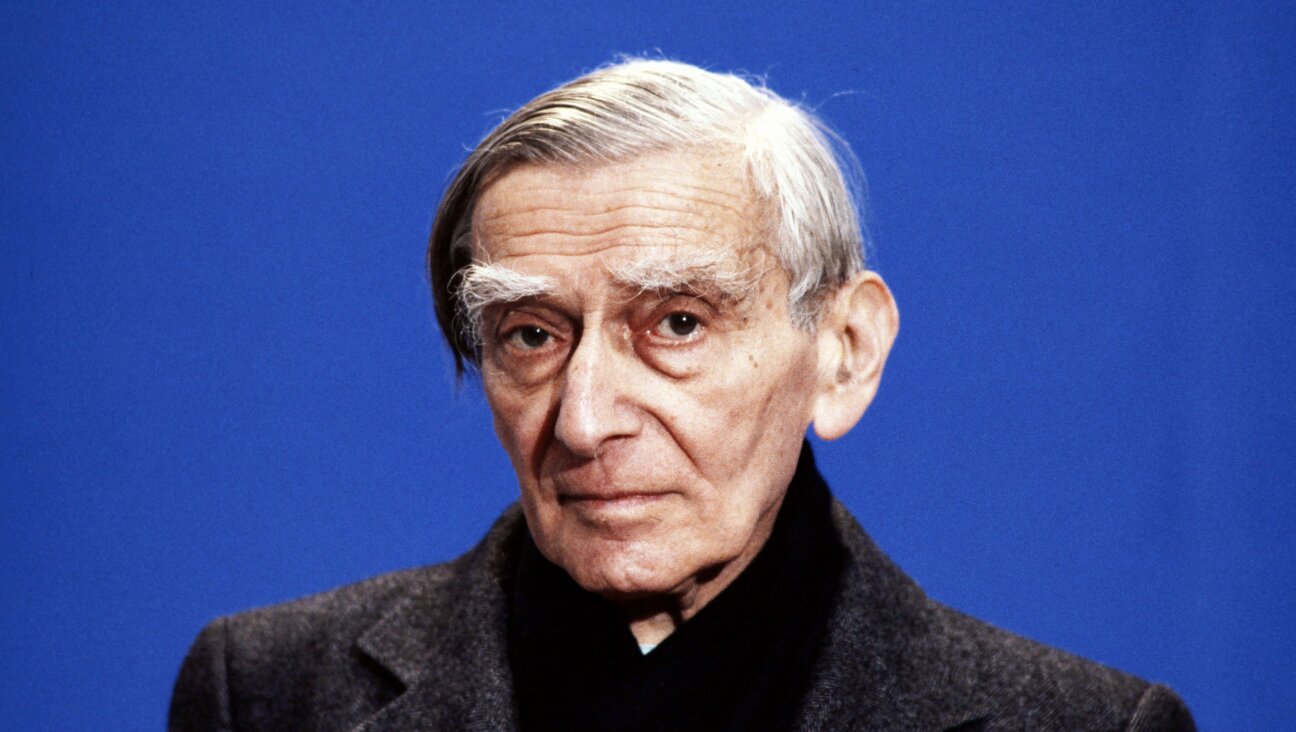

Ed Koch, circa 1989 Image by Wikicommons

The first thing I learned about Ed Koch is how unusually accessible he was.

It was September, 1977, and I was a new, eager student at the Columbia School of Journalism, passionate about city news and interested in learning photography. The school published a weekly newspaper at the time, and I wanted to be the one to photograph Ed Koch during his mayoral campaign. He seemed to be the most interesting candidate, and the one most likely to win.

Ed Koch, circa 1989 Image by Wikicommons

I figured the best way to get the assignment was to prove that I already had an established relationship with the Koch campaign. Which I didn’t. So I needed to create one, quick.

Koch was a member of Congress then, and his phone number was listed in the phone book (an ancient precursor to online directories, for those who weren’t alive then.) So I called him. He picked up after a few rings, and with only a little irritation in his voice told me the address of his campaign office. No handlers or press representatives. And he was in line to run the biggest city in America? Who was this guy?

I began to follow him around — stalk him, really. The first time he noticed me at his campaign headquarters was when he was in his back office, slurping on a container of Chinese food, and I was outside when the door opened. I snapped a picture. He looked up.

“Who are you, a detective?” he growled.

“I’m a student at Columbia Journalism School,” I meekly answered.

He shrugged.

These were the days of person-to-person campaigning, especially with a character like Koch, who thrived on the tactile, the jolt of energy he so clearly relished when shaking hands, patting backs, wading through crowds, voicing whatever was on his mind. New York City was exceptionally depressed then — dirty, crime-ridden, unwelcoming. Even as intrepid journalism students, we were cautioned against venturing into certain neighborhoods — including Riverside Park, just steps from the Columbia campus. Koch brought a kind of audacious optimism to the field and people responded.

His campaign was a family affair. His elderly father and mother were with him often. (“Vote for my son! Vote for Ed Koch!” they would happily exclaim.)

And because even then there were rumors about his sexuality, he campaigned frequently with Bess Meyerson, at the time another Jewish icon, the first one of our tribe to be crowned Miss America. (Hey, this was the late 1970s. That was still a big deal.) They were obviously friends and had an easy rapport, but it was never clear to me why she was there except to serve as a presentable, acceptable piece of eye candy and subliminal heterosexual guarantor.

Koch himself was a chore to photograph — his bald head reflected the light like a shining orb, and I spent so much time in the darkroom (another ancient invention used before digital cameras) trying to burn out the glare that I wished he would have worn a toupee! But this man was as authentic as they come.

The night of the election, Koch’s campaign was ready to party in the ballroom of a large midtown hotel. My assignment was to capture his victorious pose. Armed only with a small camera one notch better than a Brownie Instamatic, I was no match for the professional photographers with their zoom lenses and tripods in the press section. So I parked myself just beneath the podium, standing next to a woman who told me again and again that she knew Eddie Koch since he was born, and waited for the moment. He didn’t disappoint.

Years later, I was on a panel with Koch at the 92nd Street Y to discuss the 2008 presidential campaign. By then, his politics had taken a decided turn to the center-right, especially on Israel, and his persona had become even more crotchety. But he remained beloved in that grudging New York sort of way.

We chatted in the green room. It was clear that he did not remembered me from 30 years ago. I, on the other hand, will never forget him.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO