When Jews Get Embarassed Too Easily

Image by getty images

Jews are image conscious. A quick Google search of “embarrassed to be Jewish” will turn up two main hits—Jews ashamed of the state of Israel, and Jews ashamed of the behavior of certain “Hareidim” — tremblers, the Hebrew term for the ultra-Orthodox — in the Israeli town of Beit Shemesh. I should amend that statement: this Google search will turn up results for Jews with access to the media who have image consciousness about these two issues. As we all know, these are not the only kind of Jews. But let me first address these.

Jews on the left, politically and religiously, are often embarrassed by Israel’s behavior, especially when it fails to conform to a secular path. In 2011, Gary Rosenblatt, editor of the New York Jewish Week, enumerated the Gaza flotilla debacle, the chief Rabbanite, and its crackdown on non-governmental organizations as examples of “When Israel Becomes a Source of Embarrassment.”

Left-leaning Jews imagine that the outside world lumps them together with the values they see portrayed by the occupation, or perhaps by Israeli police brutality. Under the imagined gaze of the secular and gentile world, these Jews imagine that their own image will be tarnished by osmosis, by a proximity of blood, however diluted, to their Israeli brethren, especially those wielding guns or sitting in the Knesset. The burden of the imagined gaze of non-Jews rests heavily upon them.

But image-consciousness is not the sole property of Jews on the left. It is part of the tradition, any rabbi will tell you. Already in the Talmud, the term chillul hashem — profaning God’s name — begins to refer less to a verbal utterance and more to a public display, for example, “If I take meat from the butcher and do not pay him at once, Rav said” (Yoma, 86a).

The idea that one is being watched and therefore, as a religious Jew, must represent the faith and behave respectably is central to many streams of Jewish practice. No doubt, during years of exile, the fear of violent non-Jewish neighbors compounded the need to focus on chillul hashem, surrounded by those who would not let you forget what you are or represent.

One group of Jews seems to live neither with the fear nor with the burden of what non-Jews think about them. The ultra-Orthodox today (excluding those who deal with secular Jews, like Chabad or Aish Hatorah, whose work depends on making Judaism seem to fit with the values of the secular, and thus must be image conscious) seem unmoved by the outside world.

Their very insularity and relative safety makes them the opposite of image-conscious. They often look down on “goyim” and the “goyim” in their vicinity know it. This fills their less-trembling Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Secular brethren with shame.

The paradoxical identifiability of the ultra-Orthodox, compounded with their disregard of how they are being perceived, infuriates other Jews in a way that Israel is scarcely capable of doing. It is not just this that makes others wary of Hasidim. It is the idea that they are somehow ruining the image other Jews are working so hard to project is a big part of the equation.

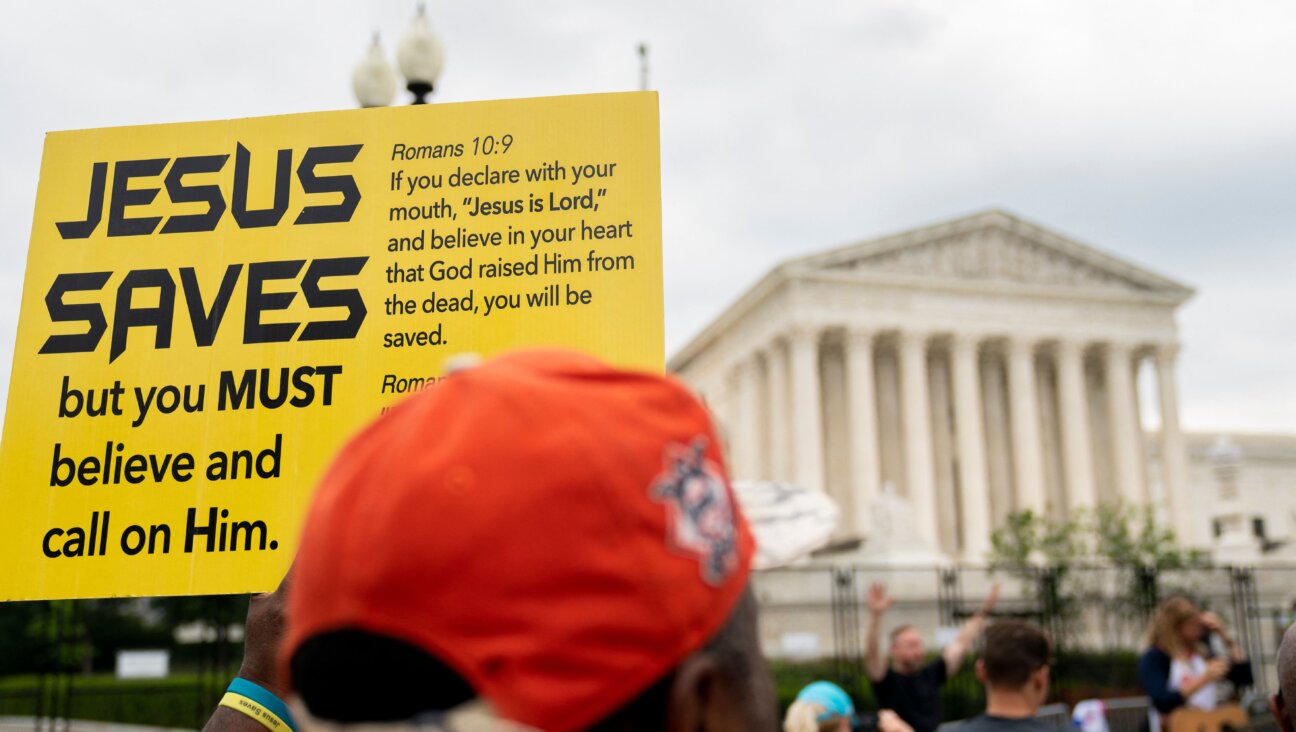

Fundamentalists of all religious backgrounds may eschew the need to be liked by popular consensus. But we should keep in mind that non-Jews may not be quite as dumb as we seem to think they are.

Non-Jews can in fact tell the difference between the practices of the Israeli military and the everyday activities of an American Jew. They can differentiate between the deeds of a child molester and those of a non-child molester, even if both are wearing a black hat. Just like Jews can tell the difference between a Catholic priest who has committed crimes, for example, and one who hasn’t. And just like we should hesitate before judging all Arabs for the actions of a minority, even if that minority appears more Muslim than their moderate brethren.

The days in which every Jew is held responsible for the actions of all the rest of us are over. Let us be the ones to lead the way to a world in which one person and not an entire faith community is responsible for his actions.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO