When Women Can’t Even Say Thank You

Image by getty images

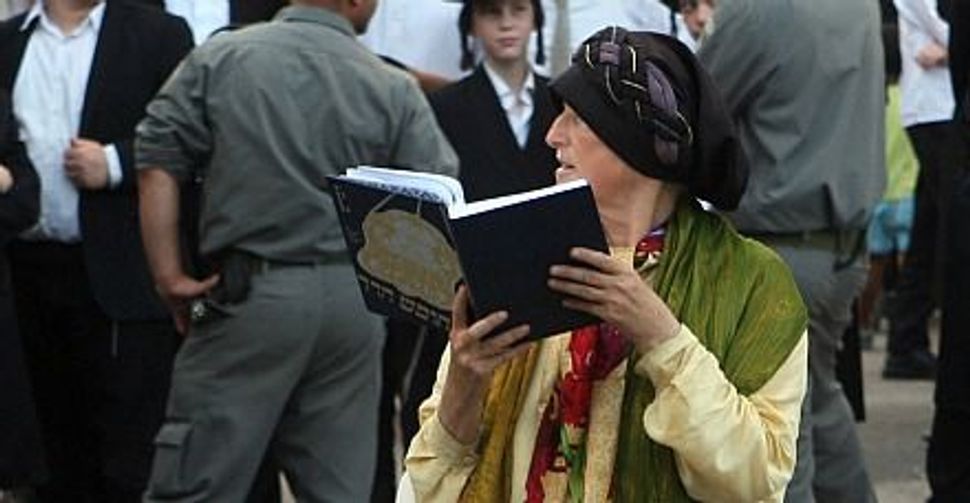

No Contact Allowed: Ultra-Orthodox Israeli women are taught to avoid all contact with men, even if it involves something as simple as saying, ?Thank you.? Image by getty images

Not long ago, on my way down three flights of stairs from the improvised nursery school where I used to take my youngest son every morning, I saw a woman struggling with several shopping bags filled with groceries. I asked her if she needed help, and when she nodded — though somewhat reluctantly — I carried the bags back up the three flights to her apartment. I tell this story not because I am vying for my neighborhood ‘Tzadik of the Month’ award, but because as I was going back down the steps the second time, I realized that something was missing: She did not say thank you.

I am sure this woman, whom I had never met and only rarely see, has excellent manners. But she refrained from acknowledging the small favor I did for her — nothing so little as to raise her eyes to mine — because in the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood in Jerusalem where I live, men do not talk to women, and women certainly not to men, not even to say thank you. It is because, as seminary girls will tell you (they hear it all day as a mantra), “It is not tznius!” meaning that this behavior is considered immodest.

Read Debra Nussbaum-Cohen on How Modesty Turns Women Into Sex Objects in The Sisterhood blog.

Amid the polemical rhetoric that has taken over what has now become a full-fledged culture war about gender discrimination on Israel’s public buses, there is another, quieter story. To be sure, the attack on Tanya Rosenblit for not ceding her place on a gender-separated bus is appalling, and the general encroachment of religious values into the public sphere is an alarming development, but beyond the proclamations, the more everyday story — an equally disturbing one — has not been fully told.

That story includes that of the woman on the stairwell. She was certainly grateful. But since she is so concerned about the public perception that both men and women may have of her, she acts in a manner that she knows — she must — to be wrong. Better to be perceived to be impolite than immodest. A few grateful words, even the wrong gesture, might be negatively construed by someone watching, betraying the fear that someone must be watching, and all the time.

Common sense civility in the public sphere has yielded to the establishing and policing of boundaries. My 16-year-old daughter, naturally modest — not just tznius in the sociological sense — told me that when a man got on a local Jerusalem bus, finding her and a friend sitting in the men’s section (the very language sounds like it belongs in the private sphere of a synagogue and not on a public bus), he pointed at them. He clicked his tongue a few times, then, with a waive of his hand, signaled them to the back of the bus.

The Shulchan Aruch, the Code of Jewish Law, affirms, “All of our women are important,” including, without doubt, my 16-year-old and her friend, yet that was certainly not reflected in the peremptory and entitled arrogance she met on the bus. True, some complain these days that the old language of chivalry objectifies women; but that chivalrous behavior is to be preferred to the dismissive treatment of women as objects who should move at the behest and slightest gesture — even approach — of a man. Without even taking into account the extreme behavior of harassment, assaults and public sphere violence, this is the other question that comes to mind: What happened to the respect for women for which Jewish men have been known for centuries?

But the answer is simple: Chivalry is dead in some parts of the Jewish world.

Walking in the neighborhood where I live, I used to, in my ignorance, greet on the street women whom I know. After all, I thought to myself, I am friends with their husbands, have watched their children grow up with mine and have sat in their homes for Sabbath afternoon meals. But most of the women — I have learned over the years, to modify my behavior — will not return my greeting. At first I wondered if there was something wrong with me. I still talk to my 16-year-old daughter’s friends. They look at me sometimes with surprise, or perhaps amusement. “He’s an American,” they probably say to one another. “He does not understand.” And the truth is, I do not understand. I am waiting to see at what age they will also stop talking to me.

As Freud underlines, relationships between men and women are always fraught, but the ultra-Orthodox treatment of the public sphere renders every gesture potentially and dangerously sexual. A sign, for a recent example, went up in many neighborhoods, forbidding the purchase of expensive foreign-made baby carriages, deemed possibly too enticing for some men to resist, their intrigued gazes in the end resting on the woman pushing them along. In a paradoxical and surprising way, ultra-Orthodox Jews — who mostly dismiss Freud’s thought — are more Freudian than Freud himself. As a result of this hyper-consciousness, they create a repressive culture of silence.

I do not want my girls constantly policing themselves, nor do I want to be surrounded by men who, in autocratic and arbitrary fashion, justify their discriminatory attitudes. I do want women, including my four daughters, to participate in the public sphere — without fear.

Chivalry may be dead, but our women are important. I want to hear — and I don’t think I am the only one — what they have to say.

William Kolbrener, professor of English literature at Bar-Ilan University, is the author of, most recently,“Open Minded Torah, of Irony, Fundamentalism and Love” (Continuum, 2011).”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO