These Jewish lawyers’ son was drafted by the A’s. Then the Dodgers picked his brother.

A whirlwind week saw Jake Gelof drafted and signed by the Dodgers and Zack Gelof’s first career hit with the A’s

Empty nesters: Adam and Kelly Gelof, middle, with Zack Gelof, left, and Jake Gelof, right, at the Oakland Coliseum during Zack’s debut series with the A’s. Courtesy of Adam Gelof

With one screen set to ESPN and another showing MLB Network, the Gelof family — Zack, Jake, their parents Adam and Kelly, and Kelly’s parents — gathered in the mancave of the Gelofs’ home in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. It was possibly, Adam Gelof said, the first time the family had all been there together since Zack was drafted by the A’s in 2021.

Now it was Jake’s turn.

Soon the call came from his agent: the Dodgers had selected Jake, 21, with the 60th overall pick — same as Zack, improbably denying lifetime bragging rights to either brother. But that was merely the beginning of the adventure. The next morning, Zack came downstairs with the news that he’d been called up from the minors. He’d be making his A’s debut later that week.

The Gelof family reunion was headed to Oakland.

“All you want as a parent is just to see your kids happy no matter what they’re doing,” Adam Gelof said in a phone interview. “And these are the dreams they’ve had.”

Starting strong

With Adam, Jake and their mom Kelly in attendance, Zack Gelof, 23, broke in his new uniform with a bang. Starting at second base, he went 4-for-12 with 3 runs, 2 RBIs and a pair of stolen bases in his first series, a run-scoring double to the opposite field his first career hit. By the time his family left town, he’d been promoted to the top of the A’s batting order.

Zack Gelof has some pop pic.twitter.com/3yuy1RYxad

— Louis Keene (@thislouis) July 15, 2023

Not that the Gelofs were going home. Their next stop was the Dodgers’ spring training home in Glendale, Arizona, where Jake signed his first pro contract.

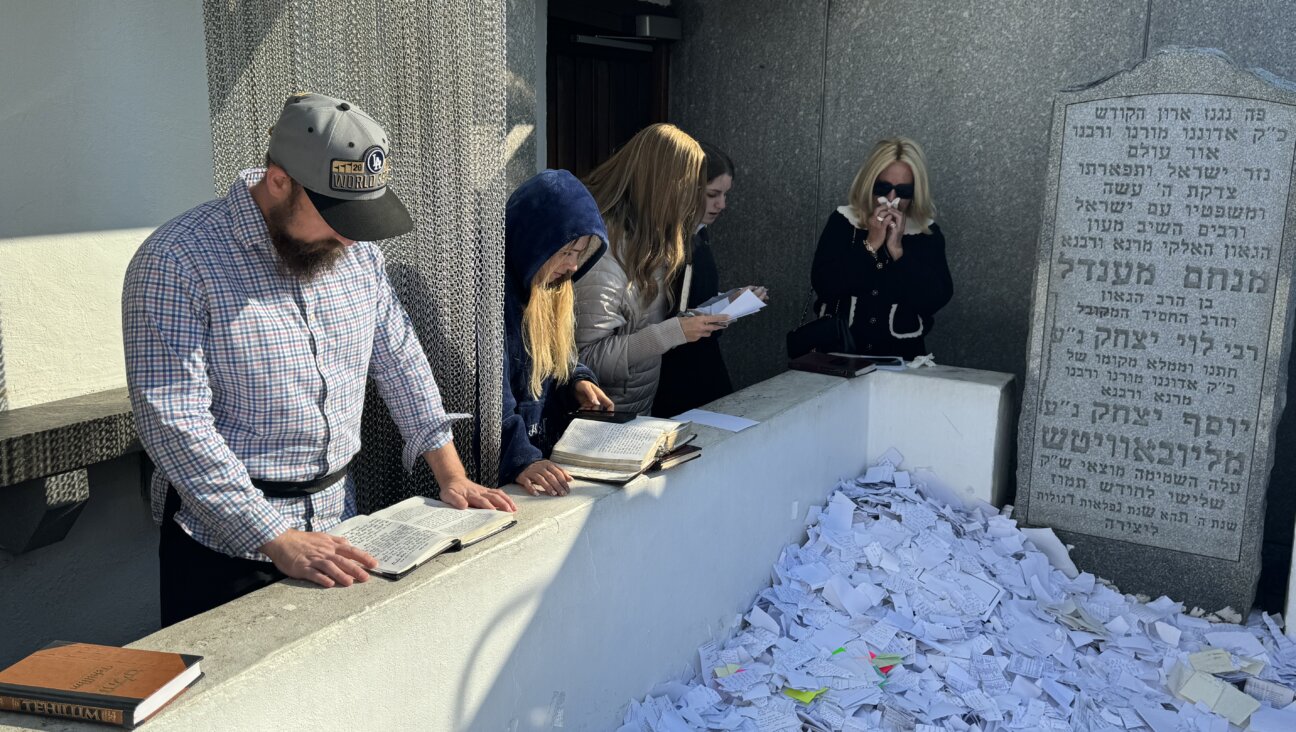

The highly touted infield prospects, whose late grandmother was the president of Dover’s Congregation Beth Sholom, are now halfway to becoming the latest pair of Jewish siblings to make the big leagues. Norm and Larry Sherry teamed up for the Dodgers when the franchise first moved to Los Angeles in 1959, and Andy and Syd Cohen played in the 1920s and 1930s, though their careers did not overlap.

Both Gelof brothers went to Hebrew school in Rehoboth Beach before attending the University of Virginia, and grew up in a home that celebrated Jewish holidays. They were not bar mitzvahed, their dad said, because religious training would have conflicted with their sports schedule.

Zack, though, has connected Jewishly to his sport, playing for Team Israel at the World Baseball Classic earlier this year. He told J. The Jewish News of Northern California in May that being raised Jewish pushed him to be a good person.

“I agree with almost all of the ideals that come with the religion,” he said. “Most of the ideals that are practiced I think I take in my life and especially through the game of baseball.”

Diamond dreams

Though the duo won a state championship together at Cape Henlopen High School, it wasn’t always obvious they’d pursue baseball, let alone turn pro.

Growing up, they were both standout basketball and soccer players. It wasn’t until a trip to the College World Series when Zack was in eighth grade — and when Adam gave a speech to the all-Delaware travel team he founded and coached — that baseball became Zack’s clear path. One of the tournament teams featured a player who had been drafted only a week or so earlier.

“Hey, that kid knows that he’s got $3 million that’s coming his way,” Adam recalled telling Zach and his friends, all of them perched in the bleachers. “And he’s trying to win a championship with his brothers — his teammates — kinda like you guys are right now. Is there anyone else that you’d rather be in the world?”

One year later almost to the day, Zack officially committed to the University of Virginia baseball team. Recruited as a two-way player — that is, both pitching and hitting — he eventually settled into the infield.

Proving himself

With Zack on scouts’ radar early on, top NCAA programs also looked at Jake, but initially passed him over, thinking he was undersized. So the younger brother enrolled in IMG Academy, a sports-focused prep school in Florida, betting he could prove himself against other elite talent.

“You go from where you’re the man to where you’ve gotta fight for everything and nothing is guaranteed,” Adam said. “I think he kind of realized that was more conducive to bringing out the best in him.”

The bet paid off — a late growth spurt helped — and Zack tipped off his manager at UVA about his bulked-up little brother’s potential, leading to a scholarship offer Jake ultimately accepted. They held down the infield corners for one season — Zack at third, Jake at first — before the elder Gelof was drafted. Two years later, Jake set the school home run record.

We have a new UVA home run king! 👑

Career HR No. 3️⃣8️⃣ breaks the program's all-time record!

📺: ACCNX | #GoHoos pic.twitter.com/KdmtcPL9ni

— Virginia Baseball (@UVABaseball) April 11, 2023

In the genes

For such athletic kids, you may be surprised to learn that both parents are lawyers whose sports trajectory topped out in high school. But their dad — and their former coach — said the competitive nature runs in the family, and they all push themselves hard. Kelly Gelof is managing partner at her firm. And as a (recently retired) prosecutor, Adam Gelof said, “if I have a bad day, someone that may have killed someone may get away with it.”

If the brothers share that edge, they don’t always display it the same way. In an interview with Rivals.com in 2021, Jake described Zack as more even-keeled, and Zack said Jake was the more animated brother.

“Zach’s maybe a little more conservative; Jake’s maybe a little bit more outgoing,” their dad said, adding that he didn’t want to “pigeonhole” his sons.

The differences spill onto the field, too, where 6-foot-3 Zack profiles as a line-drive hitter with speed and 6-foot-1 Jake, who the Dodgers drafted as a third baseman, more of a power bat.

The older Gelof, 23, was only the fourth position player in his draft class to reach the majors. If and when Jake, 21, gets there, you can bet on another family reunion.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO