These Jews were among baseball’s all-time greats — but do they count as Jewish baseball players?

If you convert after your career is over, were your accomplishments Jewish feats? The Talmudic answer is unclear.

Normal photo caption Photo by Getty Images

From a Jewish perspective, the 2021 World Series was particularly special.

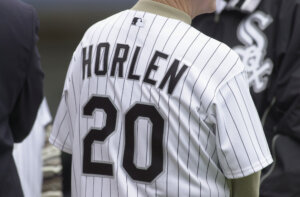

Four Jewish players appeared (Max Fried and Joc Pederson of the Braves, and Alex Bregman and Garrett Stubbs of the Astros), and all of them played in Game 6 (although not simultaneously). No prior Series featured more than two Jews. Except for 1972, in which Mike Epstein, Ken Holtzman, and Joe Horlen of the Oakland A’s appeared in at least one game.

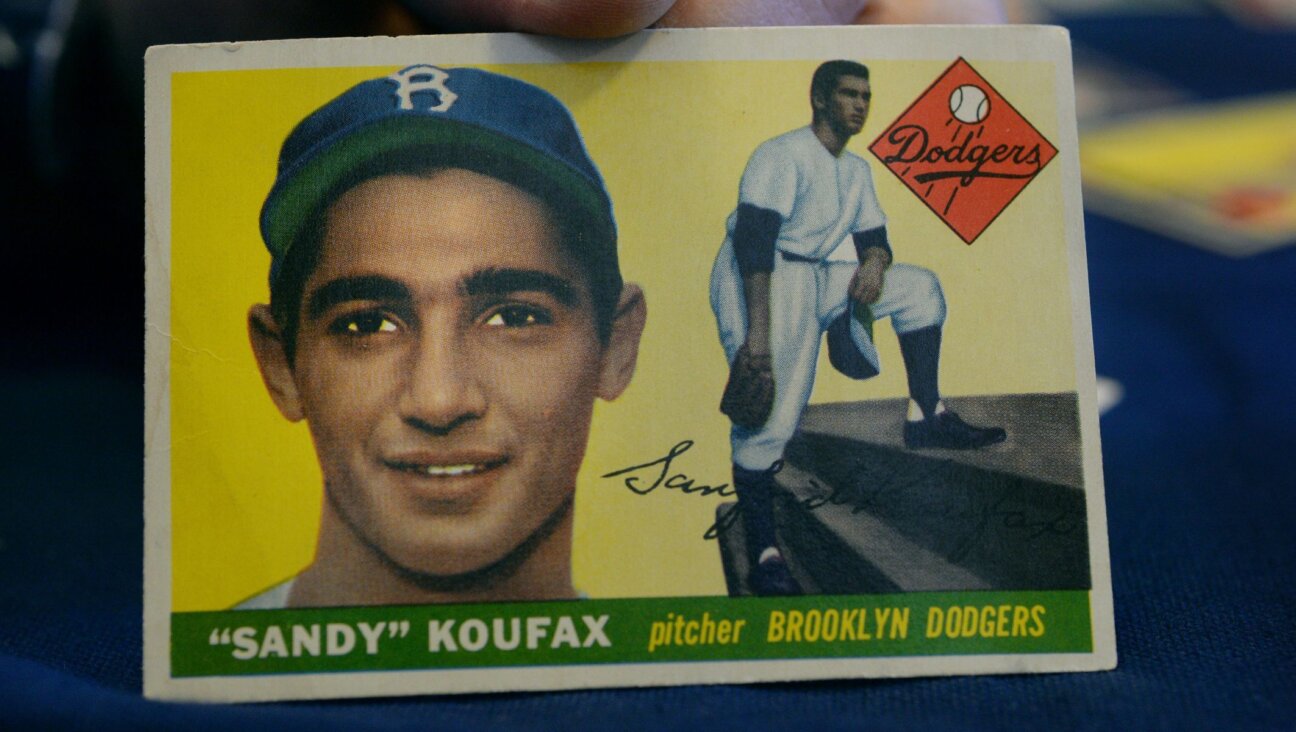

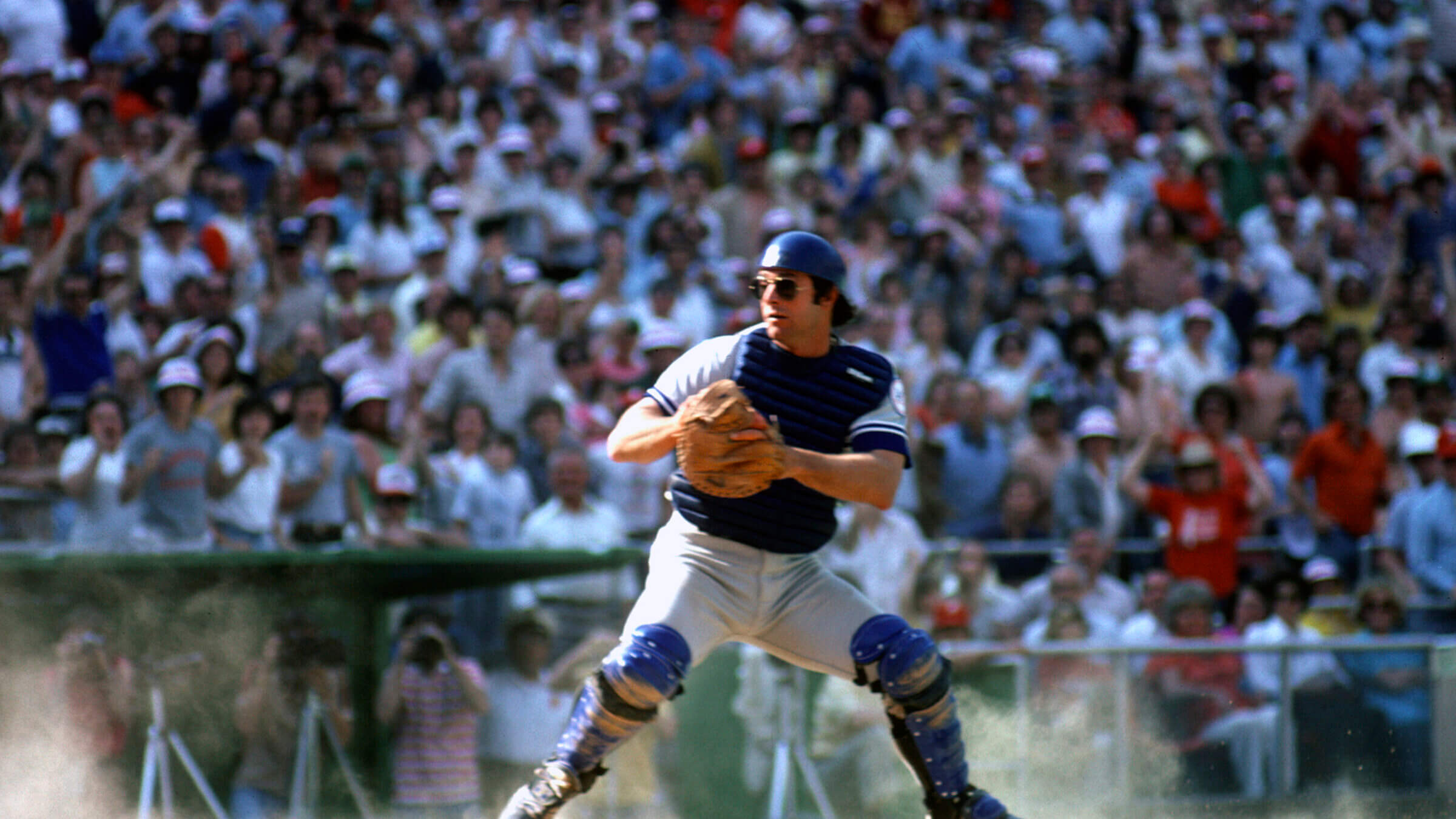

In the bottom of the first inning of Game 2 in Houston, Bregman came to the plate against Fried, the first World Series clash between Jewish pitcher and Jewish hitter. Except for Game 4 of the 1974 World Series, when Dodgers catcher Steve Yeager faced Holtzman three times, going 1-for-3 with a double and a strikeout.

So did the 2021 Series represent historic Jewish firsts or mere Jewish seconds? Were these unprecedented Jewish events or replays of Jewish events from prior Series? And how and why do we not know for sure?

Horlen and Yeager are Jews by choice, although that is not the issue. Those who ponder baseball’s Jewish history welcome converts. Some continue to include Rod Carew (thank you, Adam Sandler), although he never converted.

But Horlen and Yeager converted in retirement, after their respective playing careers were over. That presents a unique dilemma — how the historical record and conversations about Jews in baseball account for players who had not converted and were not identified or recognized as “Jewish players” when their athletic records, achievements and milestones were being compiled.

Shavuot — which commemorates the Revelation at Sinai while celebrating Jews-by-choice in reading the Book of Ruth — offers the appropriate moment to consider this question.

The baseball perspective is mixed. Howard Megdal’s “Baseball Talmud,” the authoritative ranking of every Jewish player at every position, includes Yeager but not Horlen. Jewish Baseball News and the Jewish Baseball Museum do not include either. “The Big Book of Jewish Baseball” by father-son team Peter and Joachim Horvitz includes encyclopedia entries on both players. Both appear in Ron Lewis’ “Jews in Baseball,” a lithograph depicting more than 30 Jewish contributors to the national pastime (players, managers, executives and officials), and in the short film detailing the portrait’s history.

The Jewish perspective offers multiple answers. Two Jews, three opinions, and three outs.

The simple answer is that because neither Yeager nor Horlen had converted during his playing career, neither is Jewish for purposes of statistics, achievements and the historical record. The Talmudic principle holds that a convert emerges from the mikveh with the status of a child just born, a new person, without family or history. As a halachically new person, a convert theoretically could marry his sister (but for a rabbinic decree to the contrary). According to Reish Lakish, children born to a man before he converts do not satisfy the mitzvah to be fruitful and multiply. Nothing that came before the man emerged from the mikveh remains part of his new Jewish self; although Reish Lakish did not say so, that should include records and achievements.

But Rabbi Yohanon disagreed with Reish Lakish, insisting that the man’s pre-conversion first-born fulfilled the mitzvah; Rambam accepted Yohanon’s position. This suggests that something of one’s pre-conversion life gains some Jewish character along with the convert.

More fundamentally, the simple answer rests on a restricted conception of Jews and of Jews by choice. A convert emerges from the conversion process “like a born Jew in every sense.” Judaism rejects distinctions between Jews-by-birth and Jews-by-choice; it is forbidden to harass or denigrate the latter, to treat them as different than the Jew-by-birth, or to inquire how or when a person “became” Jewish.

The simple answer also requires us to ignore how people’s lives define them. A wealth of living, experience and achievement creates a whole person and leads the Jew-by-choice to the beit din; that history contributes to their choosing Judaism, forms a Jewish person, and cannot and should not be forgotten or ignored. The Talmud thus speaks of a “convert who converts,” rather than a “non-Jew who converts,” recognizing an internal spark in one’s pre-Jewish life that provides a connection to the Jewish people and leads one on the path to Judaism.

We might extend this to the idea that a Jew-by-choice affirms rather than creates their Jewish identity. Their soul has been Jewish (and stood at Sinai with other Jewish souls); through conversion they return home — an appropriate place for a baseball player. For our purposes, the body who hit those home runs and won those games possessed an unknown and unrevealed Jewish soul. And that soul’s baseball achievements “count” among the achievements of all baseball souls, although no one knew of its Jewish nature at the time of those achievements.

A compromise approach to the baseball question distinguishes in-the-moment milestones by those who did not recognize their Jewishness from backward-looking considerations of the historical record of raw statistics by those who now publicly identify as Jews.

Thus, neither Horlen nor Yeager should count in identifying how many Jewish players appeared in past World Series or whether Bregman-Fried was the first or second all-Jew pitcher-hitter showdown. Even if pre-conversion Yeager and Horlen were Jewish in some sense or possessed of some Jewish spark, no one — including themselves — recognized their Jewishness in those moments.

Anyone reviewing the A’s roster for the 1972 World Series in 1972 would have identified two Jewish players, not three. For anyone watching Game 4 of the 1974 Series in 1974, Holtzman pitching to Steve Yeager was not Jewishly distinct from Holtzman pitching to Steve Garvey, Yeager’s non-Jewish teammate. Nothing in 1972 pulled Horlen to join his Jewish teammates in wearing black fabric on their uniforms in memory of the 11 Israeli athletes murdered at the Munich Olympics. Neither Horlen nor Yeager was expected to refuse to play on Yom Kippur, a holy day that was not part of their lives.

Looking backward, however, Yeager and Horlen alter the Jewish record book and the historical conversation about top Jewish players.

Megdal ranks Yeager as the fourth-best Jewish catcher. Yeager was among the top defensive catchers of the time, among league leaders in defensive statistics. While never an offensive threat, he hit double-digit home runs in six seasons and hit 102 for his career, 12th among Jewish players. He also is seventh in games played and 10th in RBIs. Yeager’s offensive numbers jumped in the postseason. In four World Series, he hit almost .300 with an OPS above 900 and four home runs (second among Jewish players behind Bregman, Pederson and Hank Greenberg) and shared the 1981 Series MVP (the third Jewish player to earn that award). Megdal suggests that Yeager could lay claim to best Jewish catcher on a combination of World Series performance, defense and some advance metrics.

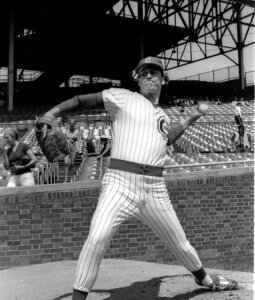

Horlen finished his career one game below .500. Yet he places fourth among Jewish pitchers in career wins (116), E.R.A. (3.11), strikeouts (1,065, tied with Steve Stone), and innings pitched (2,002). His 1967 season was, by advanced metrics, the second-best season by a Jewish pitcher not named Koufax; his 1.88 E.R.A. in 1964 is the best by a Jewish pitcher not named Koufax. His second-place finish in the 1967 American League Cy Young voting is the best Cy Young finish other than Koufax’s three wins and Stone’s 1980 win.

“Big Book” tells that Horlen ran into Epstein years later and told him about converting; Epstein responded, “‘Welcome to the tribe.’” He should have welcomed Horlen back to the tribe. And thanked him (and Yeager) for contributing an additional 116 wins, a near Cy Young Award, a World Series MVP, and an essential piece of catcher’s equipment to the story of Jews in baseball.

Rabbi Jonathan Fisch of Temple Judea (Coral Gables, Florida), Rabbi Zalmy Margolin and Mendy Halberstam aided in researching this story.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO