Krav Maga Is Trending In Paris After Anti-Semitic Incident

PARIS (JTA) — In a dark alley in a poor suburb of this city, five men with violence on their minds closed in fast on 17-year-old Netanel Azoulay and his older brother, Yaakov.

“Dirty Jews, you’re going to die!” one man yelled.

The driving dispute quickly transformed into something physical, with one of the assailants wielding a saw. Azoulay — who, along with his brother, wears a kippah — nearly lost his finger and had his shoulder dislocated before passers-by broke up the brawl.

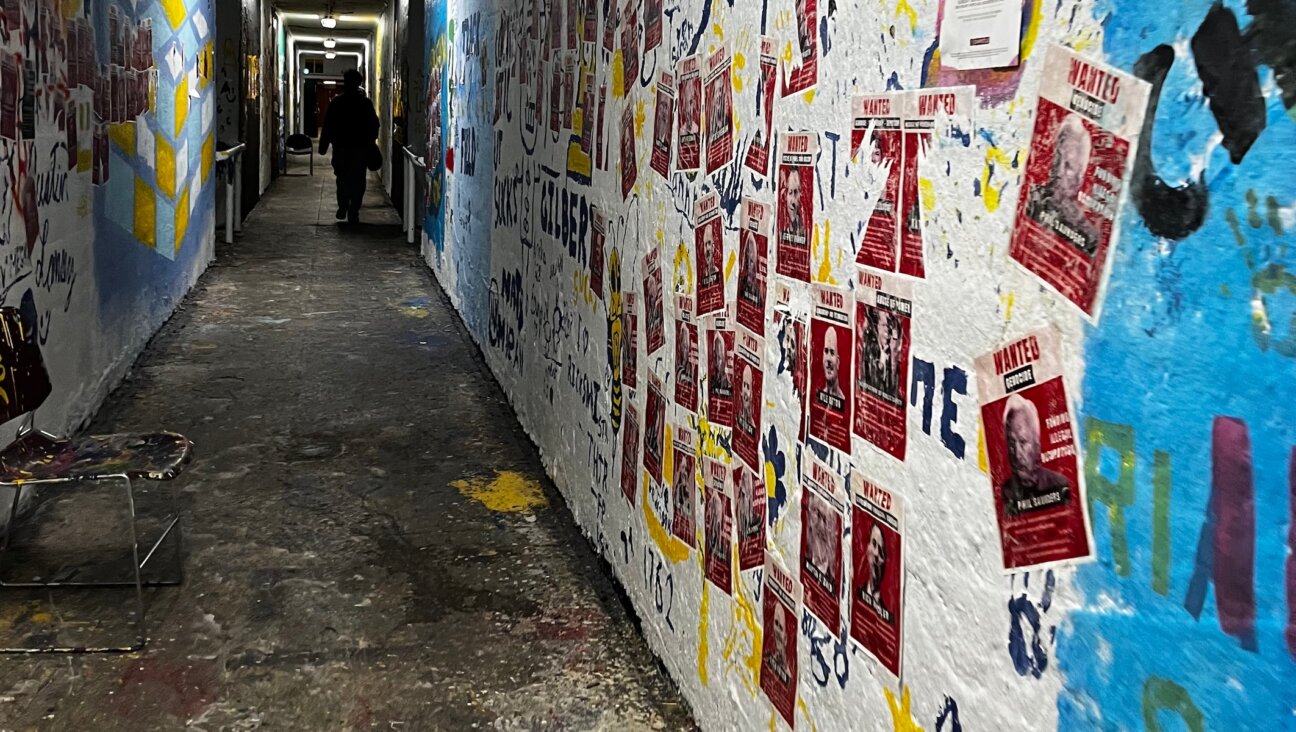

The Feb. 21 incident in Bondy was one of dozens of anti-Semitic assaults — among hundreds of less violent episodes — recorded annually in the Paris region. This altercation, however, was particularly shocking because of its bloodiness, and how it illustrated how quickly harassment can lead to bloodshed.

But Azoulay’s injuries could have been worse. Azoulay has a brown belt in Krav Contact, a variant of Krav Maga, the self-defense martial art developed in Israel. And, in fact, he has been training for such a moment for years.

“I think Krav saved our lives,” said Azoulay, who started training as a child, like his brother, in order to defend himself on Bondy’s rough streets.

Azoulay’s father is a Krav Contact instructor, and the family was an early adopter of the method when it was still largely unknown in France. Over the past decade, however, thousands of French Jews — and some non-Jews, too — have turned to Krav Maga amid a wave of intimidation and violence on the streets of France’s major cities.

“There’s an explosion in the popularity of Krav Maga,” said Avi Attlan, one of the technique’s pioneers in France.

Ten years ago, it was taught at a handful of Jewish schools in the Paris area, he said. Today, Krav Maga is taught in at least 20 Jewish schools, including many belonging to the Chabad-Lubavitch educational network. Jewish summer camps have also recently begun to offer lessons.

Attlan and the Krav Maga masters in his employ teach approximately 200 trainees in five venues across Paris. A decade ago he had about 40 students, Attlan said.

In 2013, France had its first Krav Maga championship; it’s now an annual event.

“To me, Krav Maga is a sport and a way of life,” said Attlan, an Algeria native in his 60s who stands 5-foot-4.

He said “it became a survival tool” for French Jews with the increase of anti-Semitic violence following the second intifada in 2000 — incidents in France that year rose from several dozen annually to hundreds.

A sense of insecurity is what inspired Laurent Kachauda to start Krav Maga training 15 years ago with Attlan in Saint Mande, the upscale Paris suburb where an Islamist assailant killed four Jews at a kosher shop in January 2015.

“Someone carved a swastika on my locker in high school,” recalled Kachauda, a 30-year-old accountant. “I realized someone was watching me and that they might one day attack. So I looked up Krav Maga instructors.”

Kachauda was one of 12 students at Attlan’s lesson last week at a gym in Saint Mande located just 300 yards from the site of the supermarket attack. The pupils — mostly Jews ranging in age from 17 to 50 — practiced moves in pairs and threes.

In the aftermath of the deadly attack, leaders of the sizable Saint Mande Jewish community reached out to synagogue goers, recommending they learn to defend themselves. Jewish communities across the country mirrored the awareness-raising campaign.

In some communities, rabbis recommended Krav Maga training. In others, members of the SPCJ, the security unit of French Jewry that also trains in Krav Maga, held workshops to give members a taste of the technique.

One of Attlan’s students — Jordan Ctorza, 17 — needed no convincing to sign on.

“I already wanted to be able to defend myself when they talked to us about Krav Maga at the synagogue,” he said.

During the lesson, Attlan paired Ctorza with Sylvie, a non-Jewish resident of Saint Mande. Sylvie, a woman in her 30s who declined to state her last name, signed up for Krav Maga lessons “because the streets are not so safe for anyone, and especially as a woman,” she told JTA during a water break.

She rejoined the group as Attlan gave rapid instructions in a hushed voice. Encouraging students to “hit faster” or “close up those exposed areas,” he discouraged them from chatting or giggling.

“We don’t talk — we hit, we block,” he said.

To Ctorza and many other Jewish Krav Maga trainees, the Israeli connection to the technique — part of the basic training for Israeli soldiers — makes for an emotional attachment.

“It means a lot to me that it’s something developed by my people for my people,” the teen said.

But Krav Maga offers advantages that appeal also to non-Jews in France, where hundreds have died since 2012 in a series of terrorist attacks in which Jews were not specifically targeted.

“Krav Maga is unlike karate, jiu-jitsu and other martial arts in that it has no rules,” said a Muslim Krav Maga instructor who works in the impoverished suburb of Saint Denis, north of Paris. He asked to withhold his name, citing safety reasons.

“It’s suitable for the urban reality because it’s totally utilitarian,” he added. “It’s designed to neutralize an attacker. No bows, no niceties. Only whatever it takes to thwart an attack. Kicks to the groin — fine. Thumbs to the eyes – sure. Whacks to the neck – why not.”

The Arab instructor, who is in his 50s, said he left Saint Denis for a safer suburb 20 years ago following a brawl he had with drug addicts. He recalled assaulting them near a playground where his 18-month-old son had just found a used syringe in a sandbox.

But the instructor, who has eight siblings in Saint Denis, keeps returning to teach Krav Maga to at-risk youth.

“It prevents bullying and helps instill discipline and confidence,” he said.

Martial arts, including Krav Maga, “got me out of this place, where 80 percent of my high school friends are now dead,” he said. “I hope to put others on that path, as well.”

The Muslim instructor teaches his students about the Israeli origins of the method and uses its Hebrew-language terminology, “even though many of them have a negative image of Israel,” he said.

“Religion stays outside the ring; there’s a mosque for that,” he said. “Politics stay outside the ring; there are debate clubs and youth movements for that.”

A fifth of his 80 students are women, he said. He does not train children or “people likely to abuse the weapon I teach them.”

Back in Bondy, Azoulay plans to resume his Krav Contact training once his hand is fully recovered. Surviving the attack showed him he has “what it takes to keep myself safe,” he said.

But the incident’s emotional effects linger, he adds.

“It didn’t make me afraid, but it made me uncomfortable,” Azoulay said. “I decided after the attack that I want to leave this country. Maybe for Israel, maybe go to the United States.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO