Echoes of Ataturk Seen in Turkey’s Strong Stand

When two synagogues were blown up this month in Istanbul, Turkey, the government reacted promptly and pointedly. It vowed to get the culprits. It had alternatives. It could have said that the bombing was regrettable but that America’s occupation of Iraq provoked the event. But the Turkish government said nothing of the sort. It took a straight and strong line: Get those antisemites.

This is, in the Muslim world, especially at this moment, a surprise, and a double surprise in view of the fact that Turkey is a nation whose population is more than 98% Muslim. So, what gives here? The answer, in a word, is Ataturk, which means “father of the Turks.”

A young military officer at the end of World War I, Kemal Ataturk rose as leader of what was then called the “Young Turks.” That name subsequently became a generic concept referring to a generation that challenged the assumptions of an older generation and was dedicated to modernizing an outmoded system.

A key factor in Ataturk’s drive to modernize Turkey was the Turkish military. Over some centuries, the military had risen from an enslaved soldiery into a ruling element in Turkey, a fascinating evolution that began with an institution whose Arabic name was devshirme. The practice was for the emperor to entice war captives, very young Christians and Jews to become part of military service. They were, in effect, the ruler’s bodyguards.

In time, notes the Columbia Encyclopedia, “they made and unmade governments.” In effect, the slaves became the masters.

Ataturk knew this, and he cultivated close relations with the military. He knew that in a showdown it could be the decisive force. From the time of Ataturk’s takeover after World War I, he counted on the military to back him up. In 1924, he abolished the caliphate, thereby putting an end to Islamic dominance in the government and introducing civilian rule. He put an end to the historically dominant Islamic concept of Sharia, which essentially holds that the real constitution is the Koran.

Ataturk did not generally achieve his goals in a democratic and constitutional way. He was a dictator who did not hesitate to his use fists — namely, his beloved military.

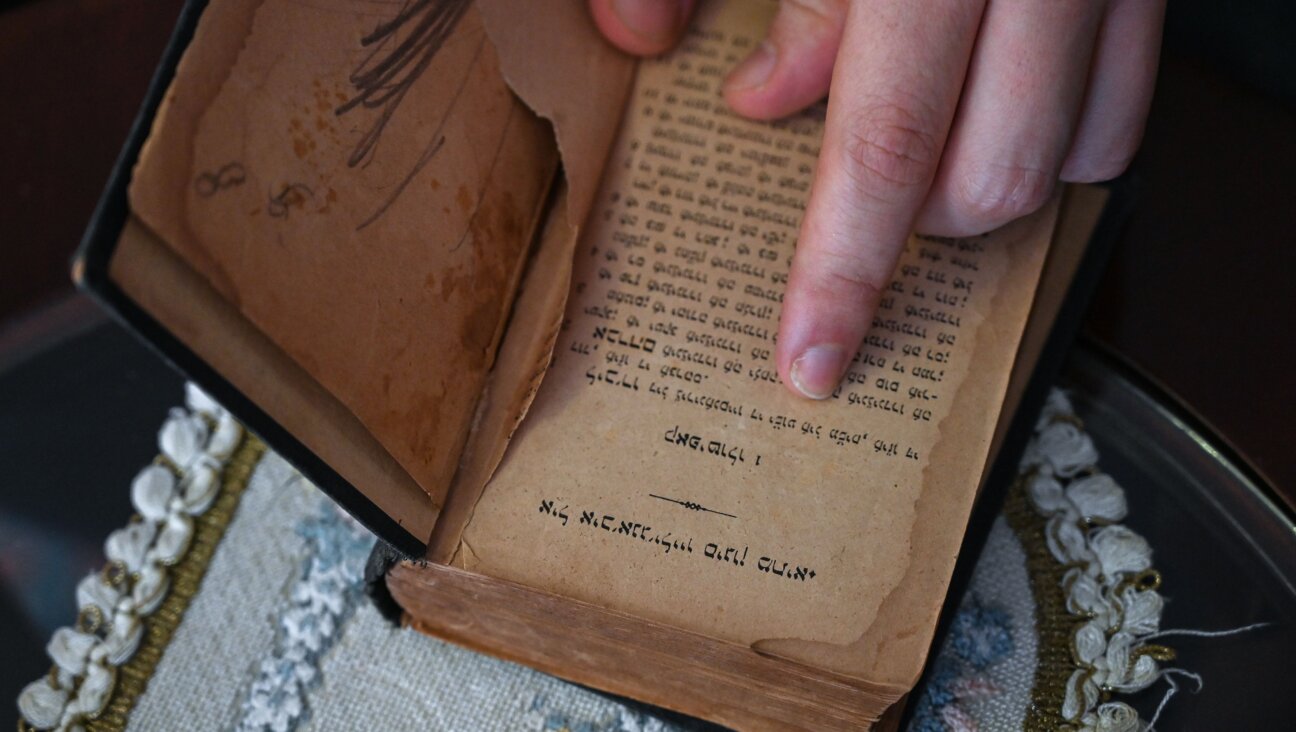

Through all this, Ataturk remained a Muslim — or a Muslim of sorts. The story is that one of his ancestors was a follower of Sabbatai Zevi, one of several Jewish “false messiahs.” Zevi gathered a worldwide following, mainly because the times called for a “messiah.” Bogdan Chmelnicki, a Cossack killer out of the lawless Ukraine, had launched a war directed against the powerful princes of Lithuania and Poland. The princes fled to cities such as Paris, Vienna and London. They left behind the Jews, many of whom were tax collectors, bookkeepers and managers of royal estates. Unable to find nobility to slaughter, the Cossacks went after the Jews.

Zevi’s time had come. People felt that because the worst had finally come the messiah would also come, as predicted. So Zevi gathered an effective army. He found himself at war with the Saracens. They defeated him. He was told that if he surrendered and converted to Islam, he would be spared and even given an honored post in the Islamic empire.

He agreed. He converted. And his followers converted. But, like the conversos in Spain, they became Muslims on the outside but remained Jews on the inside. Can it be that all these ancient factors are playing a role in Turkey today?

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO