They met at synagogue in 1961. They were buried together at Arlington National Cemetery in 2025. This is their story.

They died two weeks apart and their military funeral was months in the making

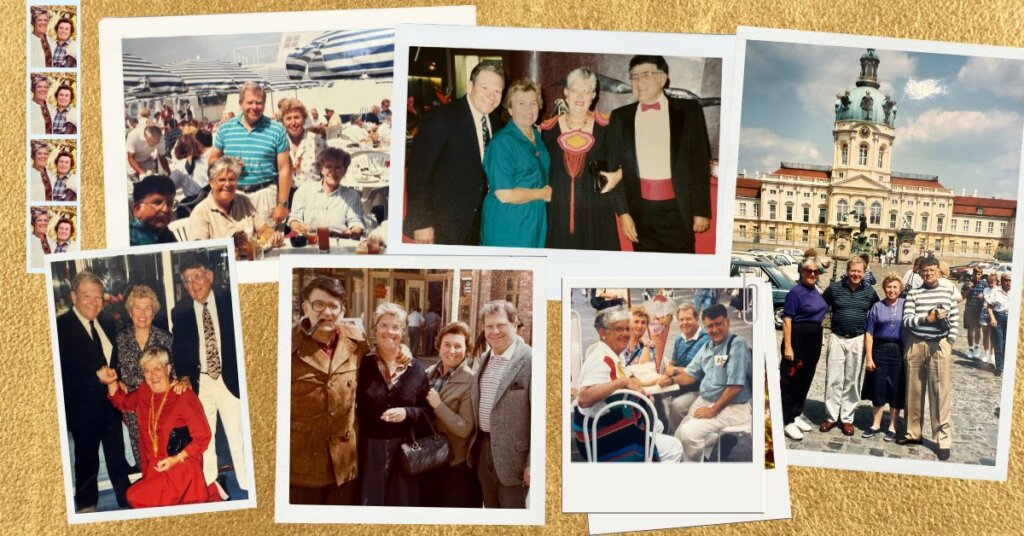

Elsie Adler, left, and Edith Kaufman were lifelong friends and wives of Navy captains. They were buried a few feet from each other at Arlington National Cemetery on the same day. Courtesy of Kaufman family

Benyamin Cohen traveled to Arlington National Cemetery for the funerals of Elsie Adler and Edith Kaufman, where he spoke with their family and friends.

ARLINGTON, Virginia — Elsie Adler and Edith Kaufman first met on a wooden pew, perched on the women’s balcony of Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, the oldest Jewish congregation in America, a place where history hums from every beam and bench.

It was 1961, and their husbands, Bob and Norm, were Navy captains stationed nearby, men whose duty demanded movement and impermanence. But Elsie and Edith were the opposite. They were a steady anchor in each other’s lives, from the first moment they sat together during High Holiday services in that sacred space.

What began as a shared bench turned into shared lives — a friendship forged by proximity and sealed by decades of loyalty. They raised their children together, followed each other from town to town as military life demanded and vacationed on cruises in the Baltic and through the icy waters of Alaska side by side.

For over six decades, they were as constant as the tides that rolled into the harbor near where they first met. And when the end came, Elsie and Edith died two weeks apart. They were buried on the same day this month at Arlington National Cemetery. There, amidst rows of markers that tell endless stories of service and sacrifice, their story found its final chapter.

A unique cemetery, a unique purpose

Edith Kaufman was 94 when she died on Oct. 21, 2024. Fifteen days later, on Nov. 5, Elsie Adler followed at 95. As wives of Navy captains, they had always planned to be buried at Arlington, where presidents lie among soldiers, the unnamed share ground with heroes, and the sacred work of honoring the dead unfolds with the relentless efficiency of a machine built for memory.

Jewish tradition wants urgency in burial, a reverence for returning the body to the earth as quickly as possible. But Arlington, steeped in its own solemn rituals, operates on a schedule dictated by the gravity of its purpose. The cemetery hosts 25 to 30 funerals every day, with burials for active duty soldiers given priority. Demand is so high that the wait to be interred can stretch from three months to a year for everyone else.

Even Ruth Bader Ginsburg had to wait a bit when she died in 2020. “I’ve probably done about 800 services here,” said Rabbi Randy Brown, Arlington’s resident rabbi, who coordinated the Supreme Court Justice’s burial. “And only a half-dozen times were we able to get it done in under a week,” he told me as we walked among rows of graves.

Brown, 51, has made a career out of navigating this strange liminal space between faith and bureaucracy. Perhaps it helps that before he became a rabbi, he worked in commercial real estate, where balancing the immovable and the urgent was part of the job description. “Sadly, you’re reopening the wound,” he said of burials that take place months after a person’s death. “But we’re writing the playbook to the best of our ability because it’s such unique circumstances.”

Brown walked me through the adjustments families have made to honor both Jewish law and Arlington’s schedule. Memorial services and eulogies are held soon after death, followed by shiva, the week of mourning. The body, embalmed and refrigerated, waits in a funeral home until Arlington calls.

It’s a delicate balance between tradition and practicality, but Brown sees it as a necessary compromise. “Even though Jews only make up about 2% of the U.S. population, we punched above our weight in World War II and the Korean War,” he said. “I’m still blessed to be burying the Greatest Generation.”

Arlington has its quirks, too, equal parts poignant and surreal. Space is finite, which means that spouses are buried atop each other, sharing a single plot in death as they so often shared in life. “I had one guy who had three wives who preceded him,” Brown said, letting a small smile break the somber air. “All four of them ended up in the same plot.”

Arlington bent its own rules for Edith Kaufman and Elsie Adler, which is something it doesn’t do lightly. They were Navy wives, yes, but they were also something more than that — two lives interwoven so deeply that separating them, even in death, would have felt like sacrilege. So Arlington made room for them both, side by side, on the same day, Jan. 16, adjusting its strict scheduling process to accommodate a friendship that had endured the better part of a century.

‘They were more like sisters’

Edith and Elsie were reflections of each other, as if some cosmic symmetry had folded their lives into a single narrative. Both families had two girls first, and then a boy, both named David. The two oldest daughters celebrated their bat mitzvahs on the same weekend, echoing the bond that had begun decades earlier on the synagogue balcony.

Edith and Elsie volunteered at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, shared leadership roles in their respective synagogues and brought the same devotion to their communities.

But even mirrors have cracks where their paths diverge. Edith was a teacher whose classrooms spanned decades and states — California, New York, Virginia and Maryland, where she became a fixture at the Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School. Teaching wasn’t just a profession for her; it was an act of preservation, a way to honor the memories of the 40 family members her Hungarian immigrant parents lost in the Holocaust. Her six grandchildren, all graduates of Jewish day schools, are a living testament to her legacy.

Elsie was a nurse, providing care in a calling that extended far beyond the confines of hospitals. David Kaufman, Edith’s son, recounted a story that has become family lore: When David was a toddler and not yet speaking, Edith worried he might be deaf. Elsie, pragmatic as ever, grabbed a pot and pan from the kitchen, marched to David’s crib and banged them together. When the boy startled, she declared, “He’s fine.” It was typical Elsie — direct, effective and unshakably sure of herself in a way that made everyone else feel steady, too.

The lives of the two families seemed guided by an invisible hand, keeping them intertwined despite the chaos of 26 combined moves. By luck or providence, they often ended up in the same cities, in the same circles, orbiting each other like stars drawn into a celestial dance. Together, they played the role of captains’ wives on Navy bases, becoming anchors for younger spouses grappling with the strain of deployments. Ruth Kaufman, Edith’s daughter, recalled how her mother and Elsie hosted the wives in their homes, offering camaraderie and solidarity when it was needed most.

Even when their lives were temporarily untethered, their connection held. They penned letters to each other long after the world moved on to emails and texts, not out of habit but because their bond demanded a kind of permanence.

“They were more like sisters,” Bob Adler, Elsie’s 96-year-old husband, said, his voice carrying the weight of a lifetime spent watching their friendship bloom. In every sense but blood, Edith and Elsie were family, twins in a life that was full of change.

‘A hoot,’ and much more

When the end came, dozens flew in from across the country to pay their respects at Arlington. Bob and Norm, their husbands of seven decades, now widowers, sat bundled in layers of coats and scarves, their faces framed by ski hats and the weight of loss. Bob’s hat bore an embroidered “N” for Navy, a quiet reminder of the shared history that had brought their families together so many years ago.

Sitting in wheelchairs, they watched as their wives’ caskets arrived, greeted with military precision by a Navy honor guard of six. The pallbearers’ synchronized steps matched the solemn rhythm of a place that demands nothing less. Overhead, flocks of geese flew in formation, while behind them, the faint roar of departing flights from Reagan Washington National Airport whispered of lives still in motion.

At Elsie Adler's funeral at Arlington National Cemetery, her casket was greeted with military precision by a Navy honor guard of six. pic.twitter.com/PrcfzH43rC

— Benyamin Cohen (@benyamincohen) January 28, 2025

Arlington’s burials are swift and exacting, measured into 15-minute services. At Elsie’s, the rabbi asked for three-word tributes. “Life well lived,” said a woman from the synagogue who used to play golf with Elsie. “A hoot,” offered another.

At Edith’s burial, her son David took a moment to reflect, his breath visible in the icy air. He spoke of the week’s Torah portion, the story of Jacob’s death, where the Bible used the word “expires” instead of “dies.” It was deliberate, he explained, a reminder that while the body may fail, the soul endures. “While Mom is no longer physically with us,” he said, “her soul and spirit will continue to carry on.”

Mourners at both services walked past the caskets, sprinkling dirt over them — a mixture of Arlington soil and earth brought from Israel. It was a gesture that bridged worlds, just as Edith and Elsie had done, to navigate a life defined by faith and friendship.

Edith and Elsie’s bond had been a masterwork of small moments, of shared seats and shared lives, of handwritten letters and inside jokes. And now, in Arlington, it found its final resting place, consecrated alongside the histories of soldiers and statesmen, patriots and partners. Memory, on this ground, is more than preserved — it is hallowed.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO