How a Jewish neighborhood in liberal Los Angeles became a stronghold for Trump

The political shift in Pico-Robertson, an Orthodox neighborhood in LA’s Westside, reflects voters with a change of heart and changing demographics

In Pico-Robertson, the two largest voting precincts swung for Donald Trump in 2024. To some community leaders, the political change was simple: “It’s Israel,” one said. But changes in the neighborhood offer a more complicated explanation. Photo by Jackson Krule for the Forward

Louis Keene talked to more than a dozen community leaders for this story. He lives in the Pico-Robertson area.

LOS ANGELES – Rabbi Mordechai Teller can’t bring himself to tell his parents he voted for Donald Trump. He grew up in a liberal Jewish household in Los Angeles, and had voted for Democrats in previous elections. But he didn’t trust Kamala Harris on issues of Jewish security, and over the years, he had become disaffected with the party that nominated her.

Teller likened his adoption of conservative politics to someone coming out of the closet — a gradual awakening leading up to a great leap. Except when it came to his parents.

“It would almost be easier for me if I told them I was gay than me telling them I voted red, to be quite honest,” Teller, 43, said with a laugh. He paused, considering it. “Yeah, it would have been. They would accept me more if I said I’m gay.”

Teller, who runs an Orthodox outreach organization, lives in Pico-Robertson, a neighborhood on LA’s Westside that is home to thousands of Orthodox Jews, and he is hardly alone in his change of heart. Notwithstanding surveys that show Orthodox Jews predominantly identifying as conservative, precinct maps showed Pico-Robertson as solidly blue in previous elections. Roughly three in four voters there backed Hillary Clinton in 2016; in 2020, about two out of three went for Joe Biden.

In 2024, for the first time, parts of Pico-Robertson turned red. Its two largest precincts swung for Trump, who received about 51% of the votes compared to 44% for Harris; on the LA Times’ electoral map of the city, those precincts connect with Beverly Hills — which has picked Trump since 2016 — to form an island the color of salmon in a blue urban sea.

Pico-Robertson is not an officially defined geographic area — it’s named for a major intersection that forms its rough middle-point — and data on who lives there is limited. A survey by the local Jewish federation, which looked at the ZIP code most closely overlapping with the neighborhood, estimated about 24,500 Jews living there in 2021; the 2020 U.S. census put the total residents in that ZIP code at just over 30,000. How many of those Jews identify as Orthodox or Sephardic was unclear.

Whatever their percentage of the total, Orthodox Pico-Robertson’s numbers are growing, and by all accounts, the community is increasingly voting as a conservative bloc. Rabbi Elazar Muskin, who leads Young Israel of Century City, one of the oldest and largest synagogues in the neighborhood, estimated that up to 90% of his congregation voted for Trump, largely because of Israel. “They really felt Biden and Harris just not supporting Israel in its time of need as it needed to be supported,” Muskin told me. The sentiment is also visible on the street, outside Jewish homes with Trump yard signs or Trump flags hanging in the window.

Rabbi Mordechai Lebhar, head of LINK Kollel

The precinct maps tell a story of a political change seen all over the country in 2024, as voters with concerns about inflation, crime and immigration — and in the Orthodox Jewish world, a frustration with mixed messaging from Democrats after Oct. 7 — looked to Trump for change. But the maps also reflect a demographic change in the neighborhood. In other words, it is not only that longtime Democrats like Teller changed their vote. It is also that the voters themselves have changed. As yeshivish and Mizrahi Jews — those of Middle Eastern or North African heritage — have established a greater presence in Pico-Robertson, the neighborhood has attracted and become increasingly defined by a conservative culture and electorate.

Though still tentpoled by large Ashkenazi Modern Orthodox institutions like Muskin’s, Pico-Robertson’s Orthodox community is today more decentralized, ethnically diverse and deeply observant, with a booming Persian population, as well as emergent Chabad, Hasidic and yeshiva-educated crowds. There are new shuls for all of them.

These ascendant sub-communities lean heavily conservative. A poll of Orthodox voters by Nishma Research in September found 93% of Haredi voters supporting Trump; while data on the Persian Jewish community’s politics is harder to come by, community leaders say the numbers are similarly stark.

“There’s a correlation between the creation of these shuls and the arrival of a new demographic constituency,” said David Myers, a professor of Jewish history at UCLA who co-authored the Nishma study and a Pico-Robertson resident. One of the new shuls, a French Moroccan congregation called Magen Avot, occupies a storefront that once held a kosher seafood market. “From gefilte fish to Moroccan spiced fish,” he mused.

A Modern Orthodox neighborhood’s yeshivish turn

A surge of migration after World War II gave Pico-Robertson its Jewish identity, but for decades it was largely a liberal, traditional one — more kosher-style than kosher certified. As an Ashkenazi, Modern Orthodox community began to take shape beginning in the 1980s, a mile-and-a-half stretch of Pico Boulevard grew into the hub of Orthodox life in the western United States. Synagogues, day schools, glatt markets, nonprofits and a borderline-sinful array of kosher dining options now attract Orthodox migrants and tourists from all over the world.

The frum-ification is still unfolding, as Orthodox outposts steadily crop up where secular spots once stood. Stan’s Produce became a Chabad synagogue. A chandelier boutique became a kosher grocer. Beverlywood Bakery — est. 1946; famous for its rugelach, but nonkosher — is now a Hasidic shtiebel. These amenities have driven up demand for housing to the extent that a teardown in Pico-Robertson now starts at $1.7 million, a local real estate agent told me.

Emerging to serve — and develop — an increasingly observant crowd in Pico-Robertson is a hallmark institution of the yeshiva world: the kollel. A vestige of Jewish life in Eastern Europe, kollels pay young men — often fresh out of yeshiva — to learn and teach Torah full-time to adults in the community. There are now at least five kollels in Pico-Robertson doing outreach; one of them meets in what was once a Chase bank, whose logo and opening hours are still on its glass doors.

The proliferation of kollels has given the Modern Orthodox community a yeshiva-world flavor. Noting that his own congregants have become more active in prayer and Torah study over the years, Rabbi Muskin said Orthodoxy’s move toward what he called “modern-yeshivish” was a national phenomenon driven by the accessibility of Orthodox education at day schools, high schools and gap-year programs.

“There’s more education, so there’s more observance,” Muskin said. “You’re sending kids to yeshiva, and then you’re sending them out to Eretz Yisrael. They’re getting inspired in Israel. I have kids that grew up here that are very yeshivish today.”

Rabbi David Zargari, founder of Torat Hayim Hebrew Academy

The most visible of the kollels, Los Angeles Intercommunity Kollel — known as LINK — has expanded since moving to Pico Boulevard in 2006. Rabbi Teller, the Democrat-turned-Trump voter, taught classes there before branching out on his own; Rabbi Mordechai Lebhar, LINK’s rosh kollel, or head, also leads Magen Avot, Myers’ “Moroccan spiced fish” synagogue.

Lebhar told me that the kollel graduates — often imported from the East Coast — have tended to stay in town, taking jobs at the local day schools and starting families here. “Kollelim are an integral part of the growth of the community,” he said. “When there’s a kollel, it attracts younger families because they know there’s places they can learn, for men and for women.”

This was the first U.S. presidential election in which Lebhar, a Toronto native who first moved to Los Angeles to study at LINK, voted as a U.S. citizen. He was not a Trump acolyte, he said, but he was not electing a role model. “If you want to go hire a lawyer, so you’ll hire the best lawyer that’ll win you the case, whether he’s a mushchas or not,” Lebhar told me, using a Yiddish word that roughly translates to dirtbag. “According to what logic dictates will be better for Torah values, right now it’s the Republican party.”

The ascendance of Persian Orthodox Judaism

Four blocks west of LINK, where a barbershop once stood, stands Shuvah Israel Torah Center, a Persian synagogue known as a “minyan factory” because it offers morning prayer services every half-hour from 6:15 to 9:45 a.m. on weekdays. Each of those eight services by definition has at least 10 men; the ones I ducked into last week attained that many comfortably.

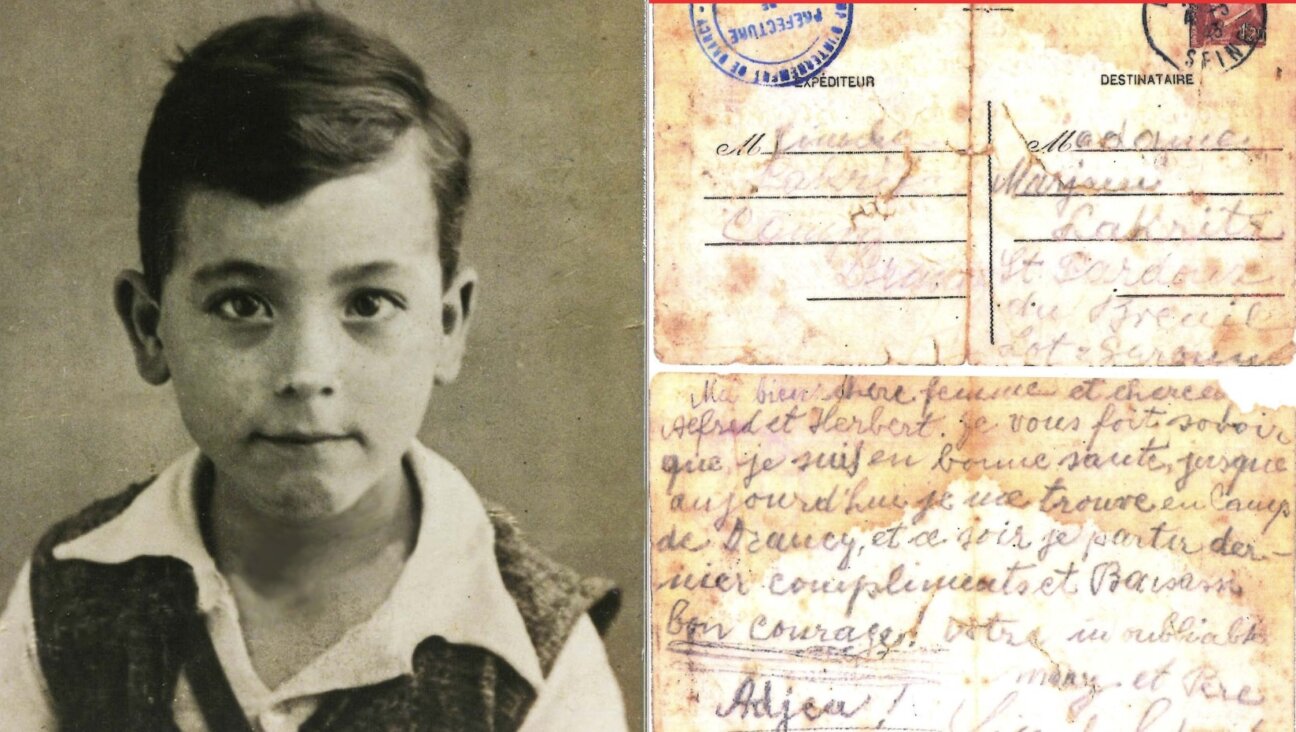

When Rabbi David Zargari arrived in Los Angeles 38 years ago, finding enough Sephardic shulgoers for just a single daily minyan was a task. Zargari, the first Iranian to attend the prestigious Haredi yeshiva Ner Israel in Baltimore, originally planned to return to Iran after graduation. But the Iranian Revolution scrambled those plans, and Zargari was dispatched instead to do outreach in LA, home to the largest Persian Jewish community in the U.S.

When they immigrated to the U.S., most Persian Jews joined Conservative synagogues, and Zargari said the notion of Orthodoxy struck first-generation immigrants as “Ashkenazi propaganda.” But within a few years of his opening Torat Hayim Hebrew Academy on Robertson Boulevard in 1987, hundreds of students were enrolled. The education they received was a Haredi one, even if their background was traditional.

As those students grew up and started their own families, Torat Hayim classrooms were increasingly filled with students from Sabbath-observant homes. By 2015, Zargari said, the transformation was complete. Some of his pupils have gone on to start their own shuls; one of them meets in LINK’s old building. Others help make quorum on weekday mornings at Shuvah Israel.

“There was a time my wife used to say that when she would see a black hat, she knew I’m coming home,” Zargari, 71, said. “I was really the first black hat in the Pico area. Now Pico has become much more black hat and much more yeshivish.”

While Pew’s 2020 survey of American Jews reported that 75% of American Orthodox Jews leaned Republican, it did not produce a Sephardic sample large enough to provide statistics on that community, the report’s lead author told me. It said 3% of American Jews identified as Sephardic, and 1% as Mizrahi. It did not offer statistics on Persian Jews at all.

But Zargari didn’t need a Pew survey to know how they would vote. “Persian Jews,” he said, “are all Republican. Republicans are much closer to us. Because Republicans have traditional values about family. And also Persian Jews are all ultra-Zionists, and they see how Obama and Biden mistreated Netanyahu. Trump is the one that brought the embassy to Jerusalem.”

“We try to push them to vote,” Zargari added. “I said, you have to vote. And they said, ‘OK, California, it’s all blue anyway’ — no. Baruch Hashem, he got the popular vote this year also. Our votes helped that.”

The formation of a new voting bloc

Israel was always the first political issue people in Pico-Robertson brought up when I showed them the election maps. Antisemitism was usually the second. But the litany of Orthodox Jewish grievances about Democratic leadership rarely ended there: crime, inflation and the culture wars all contributed to discontent.

“They’re very into the American issues,” Lebhar, the LINK rabbi, said of his community. “The economy. The woke stuff — people are sick of it.” He added: “A lot of the Jewish community, especially the frum Jewish community, that usually didn’t vote in the past, came out and voted. They were very passionate about what was going on.”

Popular vote notwithstanding, it’s hard to see an Orthodox community that makes up about a tenth of the American Jewish population — which is itself less than 3% of the national population — swinging a presidential election. But community organizers see the 2024 election as a proof of concept for local races, too.

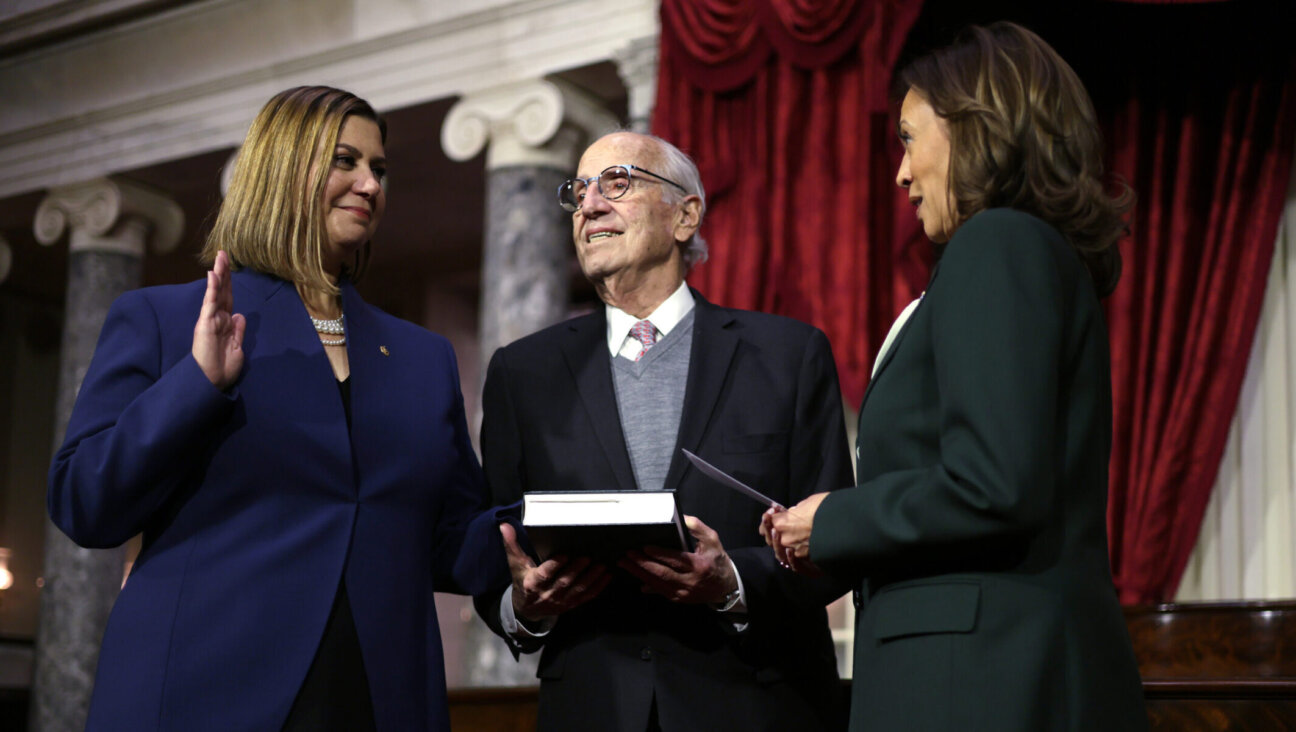

In the months leading up to the election, Miriam Mark reached out to thousands of Jewish voters as a grassroots organizer for the Teach Coalition, an advocacy group founded by the Orthodox Union. While the group describes itself as an education lobby, in Los Angeles it focused on crime, and in particular the district attorney race, where George Gascon, an embattled left-wing incumbent, was up against a Jewish former prosecutor who vowed a tougher approach on crime.

Teach volunteers hit 40 synagogues and schools in LA, many in the Pico-Robertson area, and a community-wide “We Vote Shabbat” the weekend before the election encouraged early voting. Gascon’s opponent, Nathan Hochman, won easily.

The long-term goal of the organization is to secure government funding for Jewish day schools and yeshivas, Mark told me. But she is also envisioning a more broadly powerful endgame: an activated Jewish electorate whose unity — undergirded by a demographic and cultural shift — must be reckoned with in every election, whether it’s for Congress or city council.

“The future of our community rests on the fact that you have to get out and vote, and whoever you believe in voting for that’s OK,” Mark said she told voters. “Because if we don’t create a Jewish voting bloc, no one will listen to us.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO