The Forward’s $1,000 flak jacket: The tale of an Israeli talisman

Since Oct. 7, this protective gear passed through many hands. Our reporters loved to hate it

The Forward flak jacket and helmet hanging from a balcony in reporter Susan Greene’s apartment in Jaffa, center. Clockwise from top left, our reporters in Israel: Laura Adkins, Jacob Kornbluh, Arno Rosenfeld and Greene. Kornbluh is wearing a different vest. Photo by Susan Greene (jacket); Rina Castelnuovo (Rosenfeld); Yair Yephet (Greene); others courtesy of Laura Adkins and Jacob Kornbluh

It’s been lugged through bombed-out kibbutzim, dragged around East Jerusalem in a garbage bag, and mocked by locals as it hung from a balcony in Jaffa. It’s been secured by strangers amid crying babies and guitar-playing teenagers; left in a hallway with a mysterious package of cookies, and transported around the country by taxi and military van.

It’s a flak jacket that a frantic Forward journalist bought for $1,000 in the first days after the Oct. 7 Hamas terror attack on Israel, and its odyssey is something of a window into our coverage of the war that has raged ever since.

The Israel Defense Forces required protective gear, like the jacket, on guided visits to attack sites. And at first, each reporter who took custody of it treated it like a precious object — which made sense, given its price tag.

But over time, they came to resent it. It was hot and heavy, yet seemed too flimsy to protect against a bullet.

Did it keep them safe? Depends how you think about it. As a character in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “Three Tales” put it, “Not every talisman works.”

And yet, our reporters all came home unharmed.

Procuring the jacket

Laura E. Adkins, then the opinion editor of the Forward, started making plans the day of the attack to report from Israel. Those plans included getting the gear she’d need to stay safe. She asked friends who’d worked in Ukraine as well as her stepdad, who sold guns in Missouri. But bulletproof vests, considered military equipment, are illegal for most people to purchase or possess in New York. Laura figured it’d be smarter to procure one once she arrived in Israel.

But by the time she managed to get a flight on Oct. 10, “all the vests were sold out or super expensive,” Laura told me. There was also demand from locals and from foreign journalists descending in droves.

She used every connection she had. “I emailed every person I know in Israel, friends of friends, my synagogue, my women’s group, and everyone I knew that had been to Ukraine,” Laura recalled. No luck.

Eventually, she saw someone posting about a grassroots effort to provide vests to the IDF. She connected with the organizer through the brother of a college friend. He had the goods, but was in a settlement in the occupied West Bank, while Laura was in Jerusalem. A photographer — the aunt of a former boyfriend — had her ex-husband pick it up.

The $1,000 she paid — for the vest and a helmet — was less than the $1,450 Laura saw quoted elsewhere, but twice a typical price. To make the payment, Laura Zelled the money to a friend from NYU who now lives in Tel Aviv but still had a U.S. bank account. The friend sent the money to someone who paid the seller through an Israeli app.

“When people ask me what it was like reporting the first week after Oct. 7,” Laura said, “that is the first thing I tell them about — the sheer chaos and having to work every connection to get that jacket.”

‘We’ll be sending more people there’

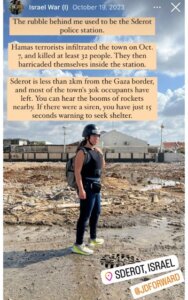

Laura wore the vest to Sderot, where Hamas destroyed a police station, and to Kibbutz Be’eri, where 132 Israelis were murdered and 32 people kidnapped. She also wore it to report on a Bedouin community unprotected by Israel’s Iron Dome, and for stories from Hebron and the Kidron Valley.

But the vest was neither comfortable nor reassuring. It was cushioned with foam, not the more customary ceramic plates. Was it bulletproof? “I’m honestly not sure what it would have stopped,” Laura said.

Before leaving Israel Oct. 31, Laura texted Jodi Rudoren, our editor-in-chief: “What should I do with the vest?” Find someone in Israel to hold onto it, came the reply.

“We’ll be sending more people there,” Jodi noted. “We don’t need it here.”

Stored in a garbage bag

Two weeks later, Jacob Kornbluh, who covers politics, landed in Tel Aviv. He was scheduled to tour Kibbutz Kfar Aza, where 52 people were murdered, with a delegation of New York officials the next day. Flak jackets were required.

Laura had left the Forward vest with a friend who handed it off to another friend in East Jerusalem. “I only had one window to pick this thing up, at 9:30 at night,” Jacob recalled. Buses run infrequently to the area, so he grabbed a cab.

“It was a very quiet neighborhood in a complex of buildings that looks like a mukataa,” Jacob told me, using an Arabic term for a labyrinthine compound. He wandered around looking for the right apartment and found a family with teenagers living there; as the mother handed him the jacket, he heard someone playing guitar.

The jacket was “very heavy,” Jacob said. “It’s bulky.” The woman gave him a garbage bag to put it in. And that’s where it stayed. Jacob didn’t end up taking the jacket on the tour the next day. Instead, he got a vest from a friend who knew of an American organization supplying gear to IDF soldiers. The real thing weighed 40 pounds, but he said he felt “more secure” using it. But it was also a little “weird, because I would go on this tour looking very much like an IDF soldier.”

Jacob had to return the 40-pound vest that night, so he took the Forward vest with him a week later on a tour of Kibbutz Nir Oz, less than a mile from the Gaza border, where 117 residents were killed or kidnapped and 60% of homes destroyed.

But the guide said they didn’t have to wear their vests, and like half the reporters on the tour, Jacob didn’t. Then, as they stopped at the gate that terrorists had broken through, “a siren went off,” Jacob said, signaling an incoming rocket. The group had 15 seconds to run to a bomb shelter. Even without wearing the jacket, Jacob told me, he felt fine.

“If I were in Gaza,” he noted, “it would be totally different.”

A Haredi neighborhood and a pack of cookies

Jacob left the jacket with a niece he’d stayed with in Or Elchanan, a Haredi neighborhood in northern Jerusalem. He also left, in the bag with the vest, a package of tea biscuits he’d brought from London for a friend at The Times of Israel that he hadn’t been able to deliver.

Jodi was the next Forward journalist to report from Israel. Jacob’s niece seemed far away and she worried a vest that fit Laura would be too small for her, so she borrowed gear from her former employer, the Jerusalem bureau of The New York Times, for a trip to Kibbutz Nir Oz. Jodi never did wear the Times vest; her tour was disrupted by rocket sirens.

Meanwhile, the Forward vest — and the cookies — stayed put at Jacob’s niece’s house until March. That’s when Susan Greene, who’d arrived in Tel Aviv in January for a six-month stint for the Forward, retrieved it. She wanted the gear before covering Friday prayers during Ramadan at Al-Aqsa Mosque, where there were frequent clashes between Muslim worshippers and Israeli security forces.

She brought along her Israeli boyfriend, Yair Yephet, who’d grown up not far from Or Elchanan. Yair “was raised Haredi and his dad was a big rabbi in that community,” she said, “so the trip gave us a chance to poke around his old neighborhood as folks were preparing for Shabbat.”

She found the vest and helmet — with the word “PRESS” written on it in white tape — in plastic shopping bags outside the niece’s apartment door. It was early morning, and she heard little kids inside crying. That “seemed like a pretty clear indication not to knock,” Susan said.

She was befuddled by the biscuits, and left them in the hallway.

‘Felt like a clown’

Susan said she felt “self-conscious” about the gear, because Israel did not seem “nearly as dangerous as people back home assume.” She did not bring it with her to the Old City.

“I would have felt like a clown wearing and even carrying them,” she said. “Both items would have had ‘lame-ass foreign journalist who’s afraid of you’ written all over them, and nobody would have agreed to an interview.”

For the next few months, the vest and helmet hung on the balcony of the loft Susan was renting in Jaffa, gathering dust. “Pretty much every Israeli who has been to my place has mocked me about having them,” she told me.

‘It wouldn’t stop a rubber bullet’

The latest Forward employee to take custody of the flak jacket was Arno Rosenfeld, who spent two weeks in September reporting on the future of Kibbutz Nir Oz.

It took four days of phone calls, texts and postponed meetings before Arno was able to pick the gear up from Susan’s boyfriend, whose Tel Aviv apartment was 30 minutes away by cab.

Arno was dismayed to discover that both the jacket and helmet are black. He’d read that the universal color for media protective gear is blue, and worried he’d look “either like private security or a militant.” He was staying in Tel Aviv’s fabric district, and considered getting blue cloth from one of the shops to cover it.

But the bigger issue was that the jacket seemed flimsy. “It would help if someone, like, punched me I guess, or maybe if they tried to stab me,” Arno said. “But it’s definitely not stopping any bullets, not even rubber ones.”

He was thinking of going to Beita, a West Bank village where Palestinians and their supporters protest every Friday — and where a Turkish-American activist was shot dead the week before in a clash with Israeli soldiers. Rubber bullets and tear gas were not uncommon at the protests.

Arno tried to procure better gear, “but just like in the U.S., nobody sells this stuff at a store. It’s all special order, mostly in Hebrew.” Jodi worked her connections, but the vests she found were in Jerusalem, more than an hour away. Eventually, a Palestinian fixer, who works with foreign journalists in the West Bank, offered Arno a real press flak jacket and helmet. In the end, Arno didn’t need them; he skipped Beita to focus on Nir Oz.

As the anniversary of Oct. 7 approached, Jodi arranged for Arno to leave the Forward gear at Shomrim, a nonprofit investigative outlet whose articles we sometimes republish.

Arno nearly got stuck in the elevator while dropping the gear off, which would have been a fitting coda to its odyssey. He imagined the helmet and jacket staying at Shomrim for years: “Every so often someone will be like, ‘Why is this here?’ and people will sort of shrug.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO