Legal scholar Noah Feldman on the 10 Commandments, Christian nationalism and the Jewish future of church and state

A push for religious symbols in the public square is “bad for having a culture in which lots of different religious traditions including Judaism are allowed to flourish”

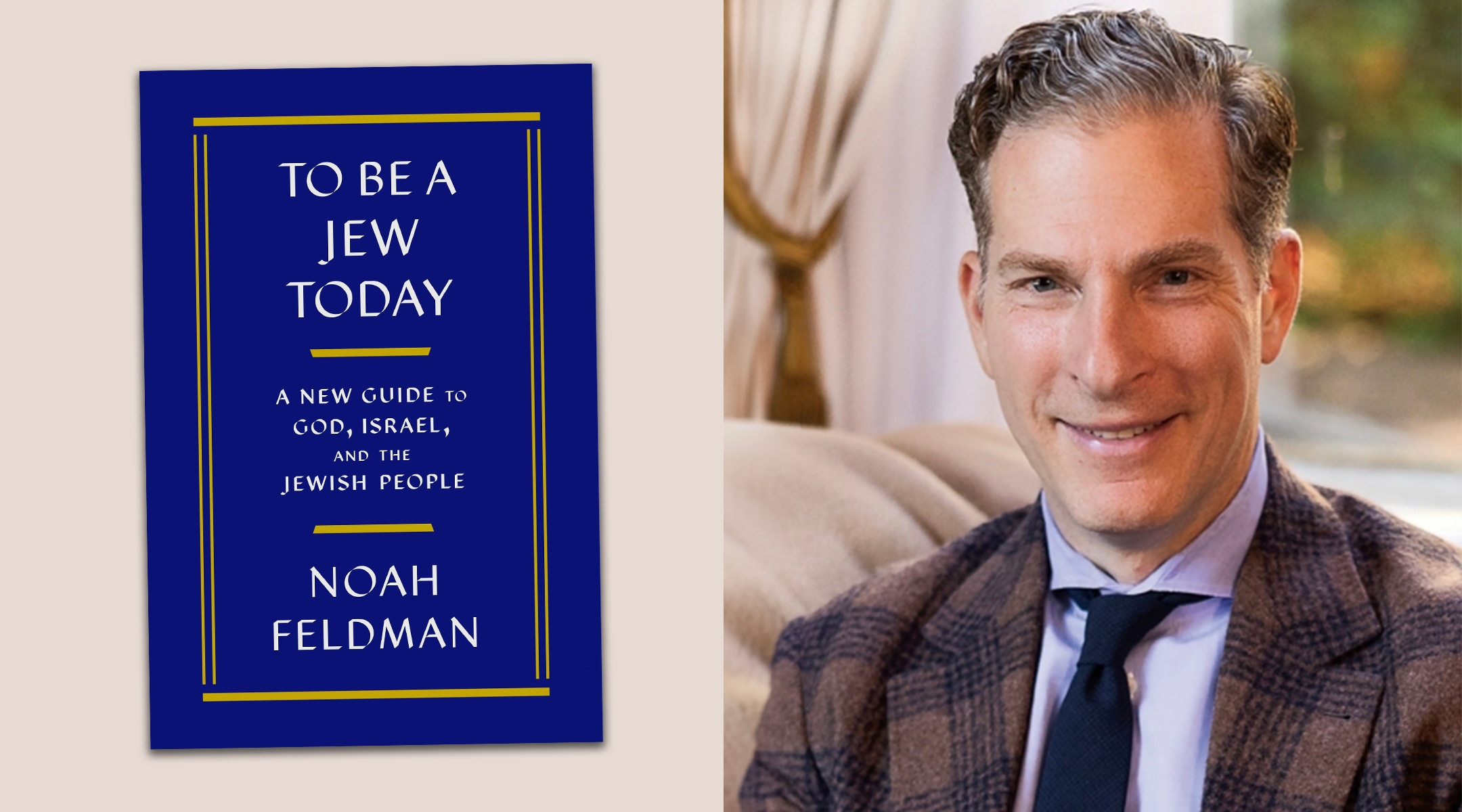

Noah Feldman, whose new book is “To Be a Jew Today,” is the Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law at Harvard University, where he is also founding director of the Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Mark James Dunn)

(JTA) — One week after Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry signed legislation requiring that the Ten Commandments be displayed in every public classroom in the state, nine families — including three Jewish families — filed suit in federal court saying the law was unconstitutional.

The law and the challenge set up an important church-state test, especially now that the U.S. Supreme Court has shown that it is much friendlier to the role of religion in public life than any court in recent years.

The law also invites a showdown between civil liberties groups and politicians they say are promoting “Christian nationalism,” or what Rachel Laser, president and CEO of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, defines as “a political ideology rooted in the belief that America was created for European Christians, and that our laws must codify, reflect and perpetuate this privilege.”

For their part, Landry and his supporters say that the Ten Commandments may be biblical but they are also a historical document that has helped shape U.S. law.

“If you want to respect the rule of law,” said Landry, “you’ve got to start from the original law giver, which was Moses.” (Similarly, Oklahoma’s schools superintendent on Thursday directed all public schools to teach the Bible, saying, “The Bible is an indispensable historical and cultural touchstone.”)

To understand these competing claims, I spoke to Noah Feldman, who is not only the Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law at Harvard University, where he teaches a class on the First Amendment, but the author of a new book, “To Be a Jew Today,” his “field guide” to the diverse beliefs and attitudes of contemporary Jews when it comes to God, Israel and peoplehood. As a result, we were able to talk about the Louisiana case not just from the perspective of the Founding Fathers, but from Jewish tradition.

Feldman, 54, who told me he got a “spectacular first-class Jewish education” at the Maimonides School, a private Orthodox Jewish day school in Brookline, Massachusetts, is the author of nine previous books. They include “Divided By God: America’s Church-State Problem and What We Should Do About It” (2005) and “After Jihad: America and the Struggle for Islamic Democracy (2003).

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

I wanted to start by talking about the religious significance of the Ten Commandments in Jewish religious life. I see the tablets in every synagogue. But are they the basis of Jewish belief the way the Louisiana governor thinks they are the basis of Western morality?

In Jewish tradition, the Ten Commandments have gotten special treatment as being an especially important expression of God’s desires for the Jewish people. But they have not been made into super law higher than the other 603 commandments in the way that we’re familiar to hearing from people of other religious traditions. The Bible treats them as highly significant and according to both the book of Exodus and the book of Deuteronomy, they were spoken by God at Sinai in a way that the 600,000-plus assembled Israelites could actually understand what was being said, as God was speaking, as opposed to the rest of the Torah.

In synagogue, the Ten Commandments are read three times a year — twice when their passages come up in the annual cycle and one time on the festival of Shavuot. Traditionally, the whole congregation stands up. But they don’t have the same role that they’ve played in Christian theology, where there’s a whole complex distinction between the first table and the second table and those commandments which are divine and those which are more ethical. There’s a whole complex Christian theology which is different from the Jewish theology. The extreme emphasis on the Ten Commandments that you get in the Christian tradition might be a little more exaggerated than what you would find in Jewish tradition. But in Jewish tradition, they’re still very darn important. They’re emblematic of the covenant between God and Israel, which is why you’re seeing them in so many synagogues.

But in terms of United States law, these are distinctly religious declarations. There’s no pretending that they’re kind of, you know, global, ethical guidelines that everyone can buy into.

The Ten Commandments are as religious as anything could be because they start with “I am the Lord thy God who brought thee out of the land of Egypt.” If that’s not a religious sentence, there is no such thing as a religious sentence. That said, it’s a complicated question in American law, and whether something that has religious origins might be transformed over time into a more secular formulation. My own view is that that has not happened to the Ten Commandments.

Louisiana’s governor wants to display the Ten Commandments in every public-school classroom. You’ve written about previous Ten Commandments challenges, and how the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision, Kennedy v. Bremerton, “overturned all existing jurisprudence about the separation of church and state.” How so?

If this were any year between say 1970 and 2022, it would be a no-brainer that the display of the Ten Commandments is obviously unconstitutional. But in 2022, the Supreme Court threw out 50 years of precedent. Before then, under the so-called Lemon test, a law needed a primarily secular purpose so as not to violate the Establishment Clause. Now the Court has said it will rely on “history and tradition” to decide such cases.

Louisiana is going to argue that by history and tradition, there’s nothing wrong with the Ten Commandments being displayed in public places, and they will point to a handful of contexts in which the Ten Commandments are displayed in which it has not been ruled unconstitutional — including, for example, a statue on the grounds of the Texas Capitol building. The Supreme Court upheld that particular display on the grounds that it had been there for a long time and no one had really ever objected to it before.

Opponents of the law will say to the contrary: Number one, the Capitol building is not in a classroom where everyone is obligated to be. Number two, there’s a big difference between a statue erected, in that case, by something called the Fraternal Order of Eagles to promote “The Ten Commandments” movie at the impetus of its director, Cecil B. DeMille, and a brand-new law, intended to inculcate a religious message.

How might this court rule, should this case make it that far?

There are three things they can do. They can deviate from “history and tradition” and go back to some version of the idea that there’s something wrong with a display that clearly sends a religious message.

Option B, they could apply history and tradition. And under Option B, there’s subset one and subset two. B-1 would be they could say this violates history and tradition: “Louisiana never had these things in their classrooms. We haven’t had these kinds of religious displays in the United States.” B-two, they can say this doesn’t violate history and tradition because at one time before the 1960s, the Bible verses were sometimes read in class and those Bible verses may sometimes have been the Ten Commandments. That would be a very surprising result.

Or the court could potentially go some completely new route, and create some new tests that they’ve never used before. But that doesn’t seem all that likely.

How significant would it be if this goes to the Supreme Court?

Let’s step back: Cases just take a while to get to the Supreme Court. And maybe between now and the time it gets to the Supreme Court, they would decide some other case that would become their first major Establishment Clause case after Kennedy v. Bremerton, where they trashed existing law.

But if it does, it will become a very important case, because it’ll be the first time they’d be applying the very ill-formulated history and tradition test.

I want to pivot to your book. Part of being a Jew today is dealing with the rise of Christian politics, whether it is the strength of Evangelical Christianity or Christian nationalism, which is maybe the sharpest point of the spear. The Louisiana law can be seen as an effort to make the country more Christian. How is that shaping Jewish attitudes, and their sense of security and belonging?

When I was a brand-new baby professor, now 20 years ago, I published a book called “Divided by God: America’s Church-State Problem — and What We Should Do About It.” A whole chapter of the book was about how Jews had played this crucial role in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s in shaping the constitutional rule that there had to be stricter separation between church and state. They had arrived a century before in large numbers, but it took the better part of a century for Jews to really make it and feel competent and enter the legal elites in a full way. And once that had happened, it was a kind of wake-up call for those who thought that the United States was a Christian nation.

As part of that process, the Supreme Court began striking down explicit religious symbols that previously had been considered nonsectarian. When I was writing this book 20 years ago, Evangelicals were trying to put up all kinds of symbols around the country that were nominally Judeo-Christian.

Today there’s a sense that Jews in the United States are facing new forms of antisemitism from both the left — which mostly takes the form of anti-Israel discourse that can veer into antisemitism — and from the right in the form of a Christian nationalism that is very different than it was 20 years ago.

Most Jews across the United States historically took the view that religious prayers in classrooms and religious symbols in classrooms were a way of effectively trying to establish Christianity as the national religion. Over the last 20 years, there has been some softening especially coming from Orthodox Jews, who have made common cause with Evangelicals and Catholics on a wide range of political issues, and feel less threatened by those faith traditions.

But you’re right that the context is now different, and I think that’s a reason for Jews to be aware and concerned. I think more and more progressive Jews will have the immediate instinct that [Louisiana’s law] is bad for the Jews, and, more importantly, that it’s bad for having a culture in which lots of different religious traditions including Judaism are allowed to flourish.

How has your own Jewish identity shaped your interest in the First Amendment?

I try to wear both hats, and it obviously depends on the circumstances. I try to write about American constitutional law descriptively and from as neutral a perspective as I’m able to muster knowing that there’s no such thing as a truly neutral perspective. I’m really trying to do that as an American.

But I’m also acutely aware of my own heritage and identity as a Jewish American. A lot of my views are probably fairly attributable to my distinctive point of view as someone who deeply identifies as Jewish, but at the same time is an heir to a very rich American constitutional tradition. That includes many mostly non-Jewish justices and writers and theorists. Some Jewish figures played a role in that, but I don’t think that an opinion by Justice [Louis] Brandeis, who was Jewish, appeals to me more than an opinion by Justice [Oliver Wendell] Holmes, who wasn’t. But when I think of my overall perspectives, for sure, being Jewish has been central to all of my intellectual projects. It can be surprising how your Jewish experience and identity will affect your intellectual processes.

What’s an example?

In the first part of my career, I spent a lot of time writing about Islam and democracy, and my Jewish upbringing was very relevant to me there too. My Modern Orthodox background made me particularly sympathetic to the claims of Islamic democrats at the time, because they were trying to reconcile Islam and democracy in a way that reminded me of the ways that my teachers had tried to reconcile traditional Judaism with modern intellectual thought.

That’s the mirror version of a common Jewish origins story — that it was the secular or assimilated Jews who were most interested in preserving the wall between church and state.

Jews who went to public schools when there was school prayer were made acutely aware of being a minority while they were in school. And it seemed really obvious that the solution was for the government to keep a much stricter separation between religion and state. There weren’t as many Jewish day schools in the country at that time, so there were plenty of people who are fairly religious who still went to public school. Now, that’s much less likely, and if you were raised religious, you probably went to Jewish day school the way that I did for 12 years. And that actually made me over time a little more open to alternative points of view about the First Amendment, because as a kid, I didn’t feel marginalized by the Christian majority.

What’s an example of one of those alternative points of view?

One of the tests that was overturned by the Supreme Court was the so-called endorsement test, which struck down any law that used religion to send the message that some people are insiders and others are outsiders. I was never a great fan of that test in my academic writing. I tended to prefer a test closer to the one that the framers had, which is, “Is anyone being coerced in this situation to perform a religious act or to be in the presence of a religious act?” So if you looked at a case like the Louisiana case, you would ask, “Is anyone coerced to be in the presence of the 10 Commandments?” And the answer is yes, every public-school child in Louisiana has been coerced. And so that violates the Establishment Clause.

Sometimes people of the older generation have said to me, “What are you talking about? The marginalization experience is so terrible!” And while I’m very sympathetic to the experience, what’s so awful about being reminded that you’re a religious minority? I mean, Jews are a religious minority. It’s okay to be reminded of an objective truth. Yeah, that was the position that I often took. And somebody said to me, “Well, that’s just because you went to a Jewish day school.” They might be right.

Your book was published in April. What’s been the most gratifying or surprising reactions that you have gotten?

Well, I would say the most surprising and gratifying thing to me was that the book actually made the New York Times bestseller list. This is my 10th book, and that’s the first time that’s happened to me.

I’ve given close to 100 book talks and I’ve been really struck that the message that most resonates for people is that we as Jews are best understood as a large, loving and somewhat dysfunctional family. And while we disagree a lot about many, many things, we should be capable of disagreeing from a place of love. And sometimes when we’re mad at each other, we should remember that we’re mad at each other the way relatives get mad at each other.

And it’s not that the stakes aren’t really high, because obviously they are. It’s that there’s a distinctive way that we’re capable of being at our best when we’re disagreeing with our family, which is that we know that at the end of the disagreement, we’re still family. We still need each other; we still love each other. And even if we’re not talking for some period of time, we’re still family. That was not my first thought when I started writing the book, but it’s where I ended up. And I was really struck that it has resonated more than any other single element of the book.

Do you think that is part of a post-Oct. 7 phenomenon, where both feelings of familial solidarity and deep disagreements have been intensified?

We were traumatized, or retraumatized, by Oct. 7, which most Jews did not experience merely as an attack on Israel, but as something with echoes of the Holocaust and pogroms. But in the subsequent eight months of war we found ourselves pretty deeply in disagreement with each other. In that environment, Jews are thinking really seriously about what it means to disagree while still being Jews. And I think that might be why the idea of Jews as family resonates for people. We understand that we all share a lot of things in common and that we also are capable of some pretty serious and principled disagreement. It comes from really different fundamental commitments of beliefs and values, including Jewish beliefs and values.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO