Leftist group exhibits art on Israeli streets to avoid censorship

The art collection depicts war as experienced by kids, including Palestinians — a topic organizers say deserves more empathy among Israeli Jews

Ariel Asseo’s painting of a father cradling his dead son is featured in an Israeli art exhibition about war’s impact on children. He hopes it will prompt conversations about Israel’s war in Gaza and policies in the occupied West Bank.

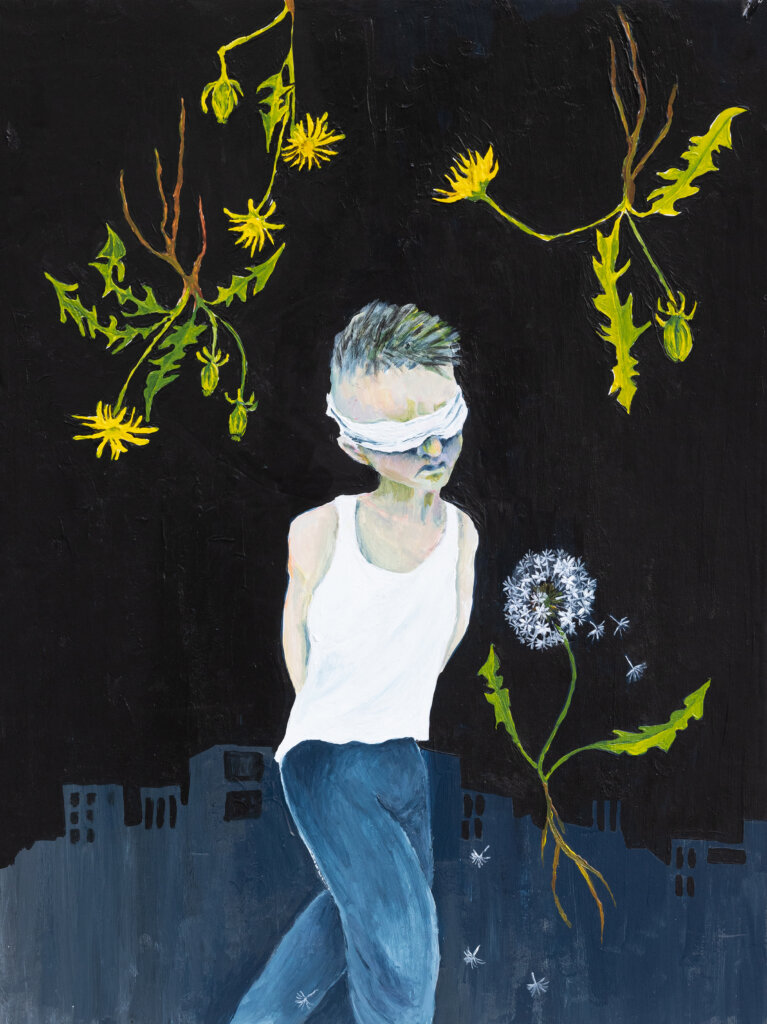

TEL AVIV — It’s dark, even for nighttime. A Palestinian boy of about 12 or 13, hands cuffed and eyes blindfolded, is being walked out of his shadowy city through a field of dandelions.

“Maybe he threw a rock or shouted at a soldier, or maybe they’re detaining him for no reason at all,” said Iris Stern Levi, an Israeli artist and social activist who painted the scene, acrylic on canvas. “From his point of view, can you imagine the terror, the tragedy of it — being dragged from your family into who-knows-what in the pitch-black darkness?”

Her untitled work is among 70 pieces in Innocence Disrupted, a pop-up art exhibition about childrens’ experiences in this time of war. The show, organized by a grassroots group called Parents Against Child Detention, debuted this spring with an outdoor showing in a central Tel Aviv square and a week-long run in a Jaffa municipal building, and organizers plan to show it in Jerusalem and other Israeli cities this summer.

The group usually focuses on ending what it sees as abuses by Israeli authorities arresting Palestinian youth in the occupied West Bank. But since the fall, it has been broadening its message to show Israelis that children are victims of Israel’s war in Gaza and West Bank policies as they are of Hamas’ Oct. 7 terror attack.

The Hamas-controlled Gaza health ministry estimates that 14,000 Palestinians under 18 have been killed during the war. The Israel Defense Forces counts 38 minors among the 1,200 killed on Oct. 7, along with 37 of the 250 abducted to Gaza. (Most of the kidnapped children were returned during a weeklong ceasefire in November.)

“Outsiders may not realize how much Israelis and our media have turned a blind eye to Palestinian kids losing their homes, their parents, being starved and killed in Gaza,” said Moria Shlomot, a lawyer and artist who runs the coalition of mostly Jewish activists.

“This project says what lots of Israelis refuse to hear: that a child is a child and their suffering is the same.”

The exhibition’s curator is Ido Bruno, the former director of the Israel Museum. He put out a call in February for artists to submit work. What he calls the “quick and dirty” collection of 70 paintings, drawings, illustrations and sculptures — some by internationally known artists, some by students in art schools — includes five pieces by Palestinian citizens of Israel, a few of whom contributed anonymously for fear their participation could be criticized for normalizing Israel’s rule.

Several of the Jewish artists I spoke with understand Palestinians’ reticence to participate in the exhibit, saying it’s mainly up to Israeli Jews to rattle their nation about the horrors of the war and occupation, anyway.

“It’s our responsibility to remove the blinders that have enabled Jews not to see Palestinians as humans and not to see their suffering,” said Stern Levi, 71.

Emi Sfard, 46, a Tel Aviv artist with a digital illustration in the show, said there are few Arab Israelis in the art world here “because they’ve been so discriminated against.”

Her piece depicts several faceless children clinging to a faceless mother. She hopes it conveys the pointlessness of continuing to wage war for political reasons and revenge.

Hannan Abu-Hussein, a 50-year-old Arab Israeli sculptor and art teacher living in Jerusalem, said she contributed to the exhibition because “as part of both communities, I believe in dialogue, and after the 7th of October, I cannot stop believing in dialogue.”

Her submission is a terrazzo tile on which she fixed a circle of six plastic baby dolls, their mouths gagged and genitals sewn with black string. She hopes it prompts people to talk about sexual violence against women and children.

Organizers planned to print images of the artworks on large, durable posters that they would glue onto sidewalks and other places where the general public, not just gallery-goers, could see and discuss them. But the city of Tel Aviv denied them permits to do so, citing zoning restrictions and safety concerns, including that pedestrians might slip on the artwork.

Shlomot, the director of the nonprofit organizing the show, said city officials also insisted that a special committee set up after Oct. 7 must approve or reject each of the 70 posters — a process she rejected for fear of delay and censorship.

Instead, her group printed the posters on foam boards and asked artists and activists to hold them at Habima Square, a cultural hub in central Tel Aviv, on April 30. The idea was to invite passers-by to stop and chat about the work.

There and at an indoor showing in Jaffa, a close-up photo of ginger hair spurred musings about the redheaded Bibas family, whose youngest member was 9 months old when they were abducted on Oct 7 from Kibbutz Nir Oz and is widely feared dead in Gaza.

A woodcut of a starving boy, his ribs protruding, prompted comments I heard at the Jaffa showing about Israel’s spotty record of letting humanitarian aid into Gaza.

A sketch of a girl holding a blue balloon surrounded by a firing squad inspired gasps of affreux — French for “horrible” — from one couple near me.

And a teenager tugged at her mother’s sleeve and said “Totally” in English as she looked at an illustration of a kid in a car seat transfixed by posters of child hostages out the window.

Other works in the exhibit include a half-burnt doll; an image of children peeking out of safe room windows at armed terrorists; and a painting of a Muslim family, held at gunpoint by soldiers, mourning a bloodied old man and baby.

Ariel Asseo, an artist from Tel Aviv, painted a bereft father squatting in the dirt, his son’s limp body in his arms. It’s a twist on the Pietà – representations of Mary cradling Jesus’s dead body.

Asseo, a father of two who teaches at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, said his painting is also a way of urging his country to grow a conscience about the civilians among the 37,500 Gazans estimated killed in the war.

“Something is wrong here,” he said. “Something is broken about the mentality of the place.”

Eiton Diamond, a human rights lawyer who sits on Parents Against Child Detention’s board, also worries that Israelis are losing their empathy.

“You’d be amazed by how subversive it can seem in Israel nowadays to just say ‘children are children,’” he said.

Bruno, the curator, said “art can spur conversations that are difficult to have and help bring to the surface issues that are uncomfortable to deal with.”

Exhibit A of the discomfort: Organizers will not disclose the specific locations and dates of the exhibit’s next showings, planned for Jerusalem in mid-July. They said they were again skipping the permitting process.

“Some conversations — especially about the harm being done every day to children, concerns about their health and security — are too important, too urgent, to risk putting on hold,” Shlomot told me.

“As a policy, we are no longer asking for permission.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO