Exclusive: Mexico’s new Jewish president has not been telling the truth about her family’s Holocaust story

A Forward investigation finds the Jewish president-elect’s mother was born in Bulgaria, not Mexico, as she has claimed

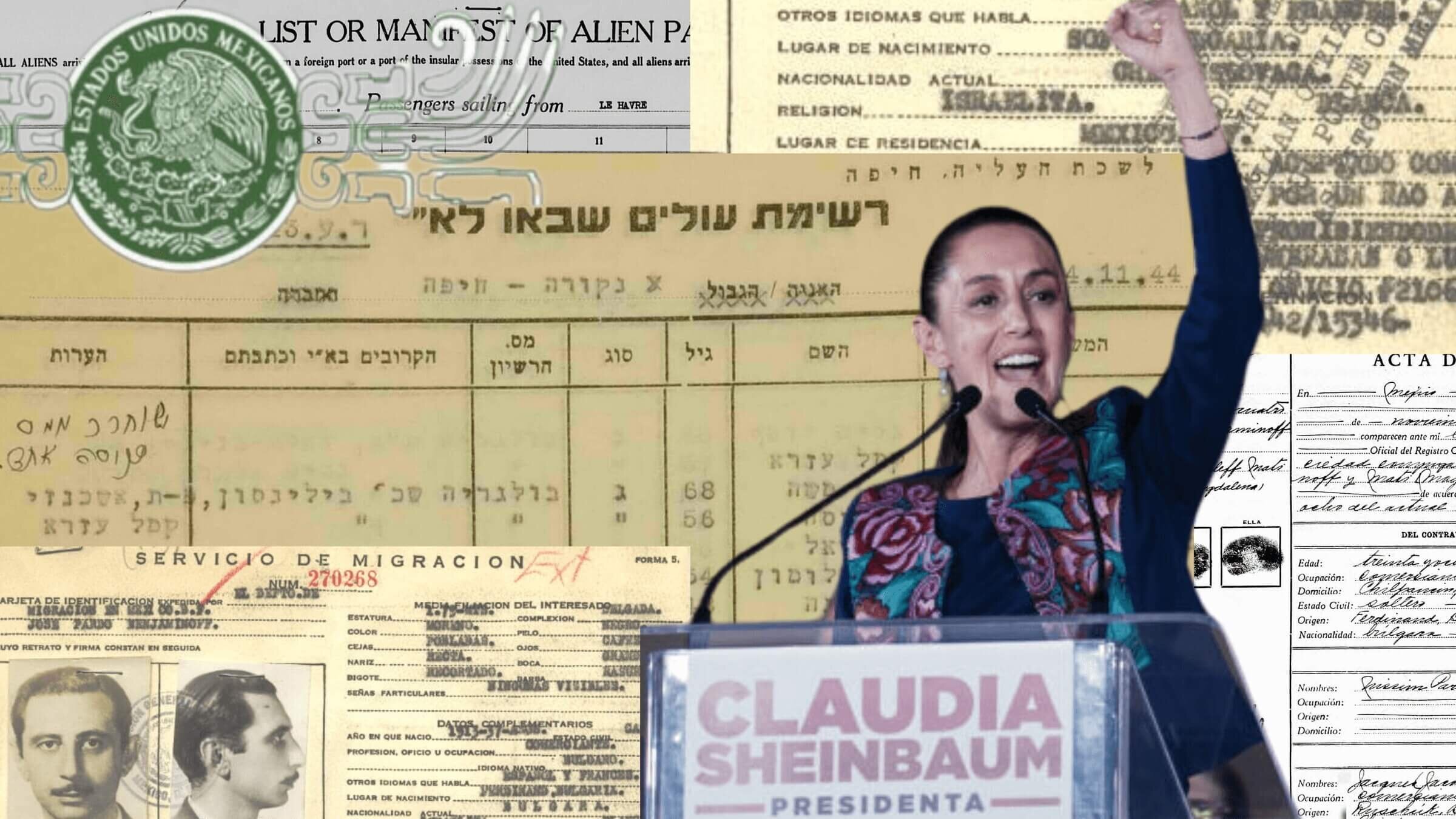

Mexico’s first female and first Jewish president, Claudia Sheinbaum, said her mother was born in Mexico. Geneological documents show she was born in Bulgaria and survived the Holocaust. Illustration by Odeya Rosenband. Photos by Luis Antonio Rojas/Bloomberg via Getty Images and the Jewish Documentation and Research Center of Mexico.

Claudia Sheinbaum, who last week was elected Mexico’s first female president, does not speak often about her Jewish identity or family history. The story she has told is that her grandparents escaped their native Bulgaria in 1940 and that her mother, Annie Pardo Cemo, was born the next year in Mexico City.

“My maternal grandparents came to Mexico fleeing Nazi persecution,” Sheinbaum wrote in a letter to the Mexican newspaper La Jornada in 2009, when she was a politically active climate scientist. “They were saved by a miracle.”

Now, a Forward investigation reviewing birth, wedding, immigration and transportation records from Europe, Mexico and British Mandate Palestine suggests that the president-elect’s family did not escape before the Holocaust, but survived it.

Where did Claudia Sheinbaum’s family come from?

Annie and her parents appear to have been among the tens of thousands of Jews who spent the war in Nazi-aligned Bulgaria. In November 1944, three months after the Red Army liberated Bulgaria, the young family arrived overland to Palestine, according to records of the Jewish Agency of Haifa that list Annie as having been born four years earlier in Bulgaria’s capital, Sofia. They arrived in Mexico in 1946.

It is unclear whether Sheinbaum and her mother have been misrepresenting their story or do not know its details. Like many wartime refugees, the family falsified documents, using a known fixer of immigration problems to create a Mexican birth certificate for Annie and witness a second marriage of her parents in Mexico City. Experts say it was relatively common for Jewish refugees, considered “undesirable,” to purchase Mexican documents to replace those destroyed or lost in the war and to secure their families’ footing in their new homeland.

I reached out to three people in Sheinbaum’s campaign on Wednesday and Thursday about this story but received no response to multiple messages.

In a brief telephone conversation on Wednesday, I told Sheinbaum’s mother, a renowned biologist and activist who was awarded Mexico’s National Science Award in 2022, about the records I’d found, and she denied that she was born in Bulgaria and lived in Palestine before Mexico.

“No, I think you’re misinformed,” she said in Spanish. When I asked when and how her parents came to Mexico, Pardo, who is 84, said: “I can’t tell you that information with precision. It was before I was born; that’s the only thing I can say.”

Annie’s uncle, Enrique Semo, a prominent Mexican historian who is 94 years old, confirmed that his sister — Annie’s mother and Sheinbaum’s grandmother — spent the war in Bulgaria, and spent about a year in Palestine before joining him and his parents in Mexico City.

“I came in 1942, she came six years later,” he said, then corrected himself to say it was actually 1946.

Semo said Annie “was born in Mexico.” When I asked how that was possible, given that the family spent the war in Bulgaria and she was born in 1940 or 1941, he said: “All the daughters were born in Mexico.” Soon he moved to end the brief conversation.

Sheinbaum, a former Mexico City mayor, was dogged throughout her presidential campaign by xenophobic attacks on her identity, including a birther-style movement peddling the false theory that she was not born in Mexico. Political opponents in the deeply Catholic country questioned her “strange last name.” The former president, Vicente Fox, blasted in all caps on the social platform X: “JEWISH AND FOREIGN AT THE SAME TIME.”

Sheinbaum, who is 61, shared her birth certificate, proclaiming, “I am 100% Mexican, proudly the daughter of Mexican parents.” She also described herself as an atheist, and played down her Jewish heritage, leaving it out when she spoke of her father’s parents fleeing Lithuania in the 1920s and her grandparent’s fleeing Naziism in Bulgaria, and making waves by wearing a cross on a string of rosary beads.

The revelations about Sheinbaum’s mother being born in Bulgaria do not affect her eligibility to lead Mexico. The country requires its president to have been born there, as Sheinbaum’s birth certificate clearly states she was, and to have at least one native Mexican parent; her father, Carlos Sheinbaum Yoselevitz, a chemical engineer who died in 2003, was born in Guadalajara in 1933 into a family of militant Communists.

But the documents I discovered detail a fascinating backstory of a small and little-known community of Holocaust survivors and refugees in Mexico. It shows the extraordinary steps, sometimes illegal, that Holocaust refugees there and around the world had to take to start new chapters in their new homes. The fact that it has been hidden for decades illuminates the long-lasting and far-reaching aftereffects of the Holocaust.

“It’s a triumph of Jewish communities,” said Ilan Stavans, an Amherst College professor who grew up in the Mexico City Jewish community and who studies Jewish and Hispanic culture, “that those that went through the Holocaust positioned their children to get an education, to feel Mexican, and to eventually be elected into a position of astonishing power to represent Mexico.”

Sheinbaum’s family tree: From Bulgaria to Mexico

The president-elect’s mother’s immigration story was told in broad strokes in an essay by Guita Schyfter in a 2022 book about Jewish Mexican women titled Tejadoras de Cultura, or “Weavers of Culture.”

“The four grandparents of Annie, the Pardos and the Semos, were Sephardic Jews from Bulgaria who spoke Ladino at home,” Schyfter wrote.

“Her maternal grandparents decided to emigrate to Cuba with their youngest son, who is now the well-known economic historian Enrique Semo,” she continued. “Annie’s parents, recently married, had decided to remain in Bulgaria. Soon after, nonetheless, they had to flee. After a tumultuous and difficult journey, the whole family reunited in Mexico City. There, the young couple’s three daughters were born.”

All but the last sentence appears to be true.

Enrique Semo, Annie’s uncle and Claudia’s great-uncle, recounted in a 2012 essay in the University of Mexico magazine how he and his parents escaped from Bulgaria to Paris in 1939 and then went to Marseille the next year. In the Vichy-controlled south of France, Semo wrote, his father Jacobo — Sheinbaum’s great-grandfather — was arrested twice for not having the right papers but both times was saved from deportation by a French lawyer friend.

Jacobo, a jeweler and banker, tried any avenue to find a visa and escape from Europe.

“My father couldn’t get into the Mexican consulate, and so he had to get a Cuban visa, which turned out to be fake, and then another one, which was genuine,” wrote Semo, a former Mexico City secretary of culture. “Later, he also managed to get transit visas for Spain and Portugal.”

A December 1941 list from the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society’s Marseille office, which I found in the online archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, includes Jacobo’s name. Next to it is the number 3, indicating family size, and the handwritten word pret, French for “ready,” which meant they had had visas but could not leave due to border closures.

According to Semo, the family set sail for Havana from Lisbon in March 1942 aboard the San Thomé, a Portuguese cargo ship, one of a few vessels the Joint Distribution Committee used to rescue thousands of Jews. But while the San Thomé was at sea, Cuba closed its doors to refugees.

The ship docked in Veracruz on April 15, 1942. “Finally, we set foot on solid ground,” Enrique wrote 70 years later. On July 15 of that year, according to their naturalization application published in the Diario Oficial de la Federación, a daily record of Mexican government activity, the Semos were entered in the National Register of Foreigners.

Enrique’s essay never mentions how — or when — his older sister Mati Magdalena Cemo, Sheinbaum’s grandmother, and her family came to Mexico.

But only 70 more Jewish refugees legally entered Mexico between May 1942, when the country officially entered World War II, and the war’s end three years later, according to the historian Daniela Gleizer’s 2014 book Unwelcome Exiles.

They came in June 1942 on the Guinée, which like the San Thomé was a medium-sized Portuguese ship. Sheinbaum’s family does not appear on the Guineé ship passenger list in the Joint Distribution Committee archives, nor on any of dozens of previous ships of Jewish refugees to Mexico whose manifests are in the archive.

Instead, Sheinbaum’s grandparents Jose Pardo Benjaminoff and Mati Magdalena Semo Calev remained in Europe, Mati Magdalena’s brother Enrique Semo confirmed when we spoke this week.

“In Bulgaria,” he said clearly when I asked where his sister spent the war. “The Bulgarians prevented the Germans from taking the Jews to the concentration camps. In that sense, Bulgaria and Denmark were the only countries that defended their Jews.”

When Bulgaria officially aligned with Hitler in March 1941, their daughter Annie was about 9 months old.

To Palestine and beyond

As in other Nazi-occupied parts of Europe, Bulgaria’s Jews were forced to wear yellow stars on their clothes, and men were sent to forced labor camps. But unlike Lithuania, the birthplace of Claudia’s paternal grandparents, where the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that 90% of the Jews were murdered, the vast majority of Bulgaria’s 50,000 Jews were alive when the country was liberated on Sept. 4, 1944.

Guy H. Haskell, author of the 1994 book From Sofia to Jaffa, said most headed to the future state of Israel, with the first waves traveling overland.

“It could be by foot, it could be by train, it could be by donkey back,” Haskell told me in a phone interview, “It was a very tricky and dangerous trip.”

Annie Pardo Cemo made the journey at age 4, according to records of the Jewish Agency in Haifa that I reviewed on the genealogy website MyHeritage.

Her name is written out in Hebrew, the last on a list of 18 refugees crossing from Naqoura, Lebanon, into Mandatory Palestine on Nov. 24, 1944. She is the youngest person on the list by 15 years. Like her parents, whose names and ages are rendered as Joseph Nissim Pardo, 32, and Makl Pardo, 21, she is listed as being from Bulgaria.

In spring 1946, the family left Palestine. They stopped in Le Havre, France, before docking in New York on June 4, according to the manifest of the S.S. Uruguay, which I found on Ancestry.com.

The manifest lists the family’s last permanent residence as Tel Aviv, and says they had a transit visa issued in Jerusalem on April 24. Annie Pardo is listed as 6 years old and born in Sofia, Bulgaria, like her mother — whose name appears as Mazalmadlen. (The manifest says her father, Jossif Pardo, was born in Ferdinand, Bulgaria.)

The manifest lists the languages they speak as French, Bulgarian and Hebrew, but not Spanish. The family gave the Hotel Nevada on Manhattan’s Upper West Side as an address in New York, and Laredo, Texas, as their final destination in the United States.

From Laredo, a border city, they headed to Mexico, where they were entered in the National Register of Foreigners on Aug. 2, 1946, according to the naturalization papers they filed years later.

There, they faced further hurdles. Gleizer explained in her book that Holocaust refugees — about 2,000 settled in Mexico over 12 years — as Jews were considered one of the “undesirable” groups by the state. They had to worry about renewing visas, which could easily be revoked, and often did not include work permission. The goal was to become naturalized citizens.

Naturalization — and falsification

Mati Magdalena, Annie’s mother and the future president’s grandmother, became a Mexican citizen in 1950, according to the summary published in the Diario Oficial de la Federación, through her father, Jacobo. He was by then well established as a merchant in Mexico, and wealthy enough to have sent his son Enrique to a military school in California.

That same year, Mati Magdalena remarried her husband, now known as José, in Mexico City, on Nov. 11. Their marriage certificate, which I reviewed on the genealogy website Ancestry.com, lists him as having been born in Ferdinand, Bulgaria, in 1912 and her in Sofia in 1923, consistent with the records of their prior entries to Palestine and New York. The couple listed their address as 39 Chilpancingo, a modern apartment building in the fashionable Condesa section of Mexico City.

One of the four witnesses on the marriage certificate is Nicolas Britt, a 52-year-old Russian who presented himself as a translator but is well known as what Mexican academics call a coyote, or fixer of immigration problems.

Britt was identified as one of two coyotes specializing in helping eastern and central Europeans obtain documents in a 2017 paper by Carlos Eduardo Carranza Trinidad, now a doctoral student in history at the College of Mexico. Migration authorities notoriously scrutinized every document and at times arbitrarily rejected naturalization applications without good reason. But Britt was known to bribe corrupt officials to create workarounds for missing documents and rubber-stamp dubious applications.

“The most notable feature of those who decided to use their services is the enormous ease with which they manage to naturalize,” Carranza Trinidad wrote. “Regularly, applicants did not reveal criminal records or health problems.”

Three months after the wedding, on Feb. 12, 1951, Jose Pardo Benjaminoff’s request for naturalization was printed in the Diario Oficial de la Federación. The entry cites their August 1946 registration but also says that Pardo Benjaminoff arrived in Mexico long before, on April 8, 1932 — when he was 20 years old, and his future wife was 8. This contradicts not only the records showing him traveling to and from Palestine in 1944 and 1946, but also the story the family told for decades afterward, about the couple having arrived at the start of World War II.

It is also in this journal entry that Annie Pardo Cemo is said to have been born in Mexico City on June 6, 1940.

Changing her birthplace from Sofia to Mexico City might have solved a bureaucratic problem and rid Annie of the stigma of being an immigrant in Mexico, but it also burdened her with a secret.

It’s a common story of Jewish refugee survival. Joseph Berger, the retired New York Times reporter, discovered in his 20s that he was born in Russia in 1945, not Poland; his parents had destroyed their documents and invented a new story to get a visa to the United States. Andrea Bernstein revealed in her 2020 book American Oligarchs that Jared Kushner’s grandparents did the same.

In a few cases, like the lawyer Allan Gerson, who came to the U.S. under a false identity in 1950, survivor children legally fixed their documents. Many others undoubtedly spent decades unable to talk about their trauma in fear that their secrets might be revealed, or may not even know their own true origins.

For at least a decade before Sheinbaum was born in 1962, Pardo presented herself as having been born in Mexico, including on public records connected to her travel to the United States.

Last year, as Sheinbaum started campaigning, Annie discussed the story with the Mexico City newspaper Reforma — how José and Mati Magdalena fled Nazism in Bulgaria, and how she, Annie, was born after they arrived in Mexico City.

“Maybe I was made along the way,” she joked, “but I don’t know.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO