‘No one’s allowed to talk to me’: At UW-Madison, trying — and failing — to talk about Israel

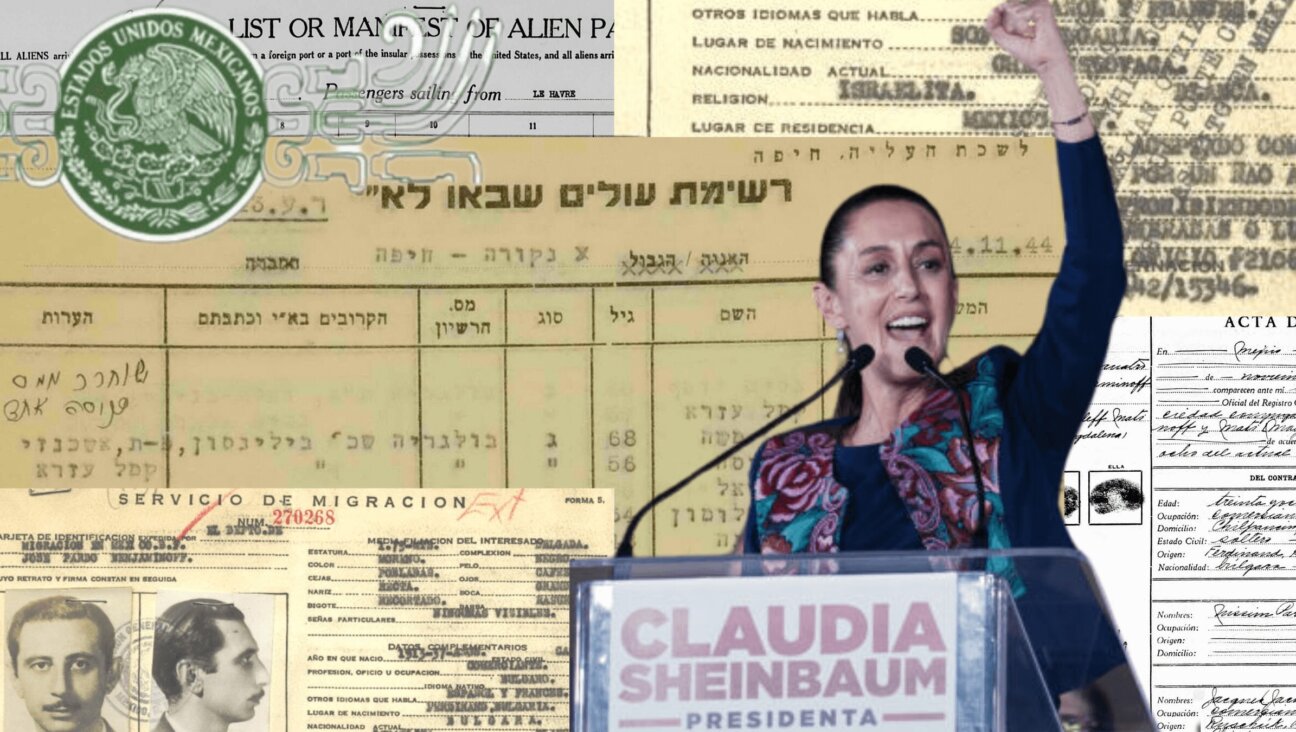

The occupation of the campus’s central piece of real estate by pro-Palestinian protesters has, for many Jewish students, brought an unsettling end to an already-difficult school year.

Pro-Palestinian and pro-Israel student activists and the pro-Palestinian encampment at the University of Wisconsin-Madison which protesters on Friday agreed to take it down in exchange for concessions from the administration. Photo by Mark Caro

MADISON, Wis. — The young woman was holding up a sign that read “Anti-Zionism Is Anti- Semitism,” which stood out amid the sea of “Free Palestine”/“Stop the Genocide” messaging on Library Mall, the epicenter of the University of Wisconsin-Madison pro-Palestinian protest. Two young women wearing neon yellow vests walked up very close to Chloe Astrachan, the 23-year-old senior from New York City who was standing in front of the fountain at the mall’s center. They kept stepping further into her personal space until she retreated to the top of the library steps.

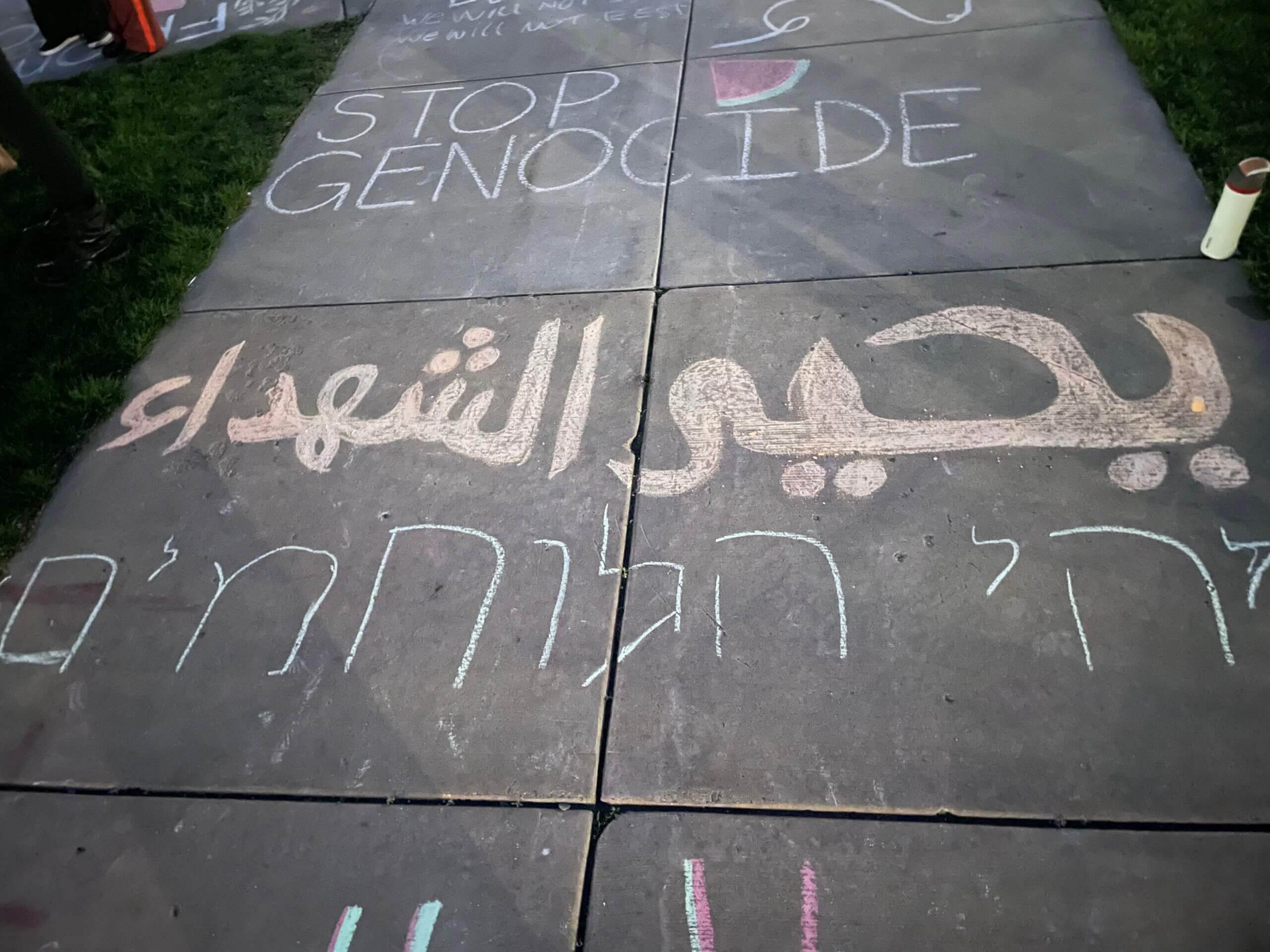

There she lifted her sign again while overlooking an array of tents and kaffiyeh-clad protestors, many of whom were picnicking or studying on the lawn or writing chalk slogans on the sidewalks on this idyllic spring afternoon last month. Early that morning, university police at Madison, as it’s known, had torn down the encampment and arrested 34 people. By lunchtime 15 tents were back on the lawn, and that number would almost double over the next day.

“No one’s allowed to talk to me because of the two girls that are wearing the yellow vests,” Astrachan lamented. “I’m standing here and protesting to have conversations, and hopefully maybe we can educate each other a little bit and all come to a civil conclusion. But if they’re not allowed to talk to a Zionist, what are they here doing?”

A man who said he didn’t want to give his name because he had identified himself as a retired judge, walked up to Astrachan to ask how she processed the loss of life in Gaza.

“Do you value human life?” he asked.

“Of course, I do,” she responded.

Astrachan and the judge continued talking until one of the women in the vests approached him and asked him not to engage with her.

“I’m not in your group,” the judge responded and continued the dialogue.

Astrachan is one of many Jewish students, who make up an estimated 13% to 14% of the school’s population, trying to find their place amid the protests and rancor that escalated on the public university’s campus in past weeks. Hillel Rabbi Andrea Steinberger said she has had many conversations with students “who are progressive but are feeling lonelier than they’ve ever felt.”

I spent several days on campus recently to find out what these Jewish students were thinking as the school year drew to a close — and how they engaged with the protesters, who have maintained a steady presence on campus since Israel began its military campaign in Gaza. What struck me most is how often conversation is avoided and impeded.

The Library Mall encampments went up two weeks ago. On Friday, protest organizers and university leaders reached an agreement to clear it. The protesters, who are demanding the school divest from Israel, promised not to disrupt Saturday’s graduation or reestablish an encampment in exchange, among other concessions, for access to university leaders who make divestment decisions.

Addressing the more than 8,500 graduates and their families at commencement Saturday, Chancellor Jennifer Mnookin spoke of the “pain and grief over the devastating destruction, injustice and loss of life in Gaza and in Israel.” Several in the audience booed her throughout her speech and yelled “free Palestine.” Security escorted several people out who had been waving Palestinian flags.

But the intensity and scale of the conflict on campus over Israel and its military campaign in Gaza have not matched that at schools such as Columbia University and the University of Southern California, both of which canceled their main graduations this year.

“Here there’s like 45,000 students, and there’s maybe a couple hundred [on the lawn],” Rachel Shela, a 19-year-old sociology student from New York, said on the third day of the now-dismantled encampment. “So the proportions are different.”

She added: “It’s also the Midwest.”

Yet the occupation of the campus’s central piece of real estate by pro-Palestinian protesters has, for many Jewish students, brought an unsettling end to an already-difficult school year.

Jewish student voices — muted

“I hear the chanting, and it makes me really uncomfortable: ‘There’s only one solution, Intifada revolution,’” said Shela, whose reaction to the trauma of Oct. 7 was amplified by her having spent a gap year in Israel. “The language of ‘one solution’ really conjures up the Final Solution.”

Ben Newman, a 22-year-old senior from Philadelphia, told me the time he felt not just uncomfortable, but unsafe — because of signs held by a protesters. He said the slogans he saw included “Glory to the resistance,” “Glory to the martyrs,” “Death to America,” “Down with Israel” and “Israel is not real.”

Zachary Ogulnick, a 22-year-old senior from Dallas, said he hasn’t felt in danger on campus, but he finds it threatening “when they are chanting things over there such as ‘Globalize the Intifada’ and ‘From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.’”

But some Jewish students support the protests and interpret their chants and signs differently.

During the encampments first week, Peter Fishman, a 20-year-old psychology major from Milwaukee’s north suburbs, was wearing a Star of David around his neck, a black T-shirt depicting “The Golem” and a black-and-white kaffiyeh with an upraised fist coming out of a Palestinian flag.

“‘From the river to the sea’ I don’t feel is a cry calling for Jewish genocide,” Fishman said. “I feel that a lot of rational people who are pro-Palestinian understand that the only way to proceed with this is to have open discussions, communications with Jewish people, because closing off one side to that is not productive for a compromise or achieving that goal.”

That said, what many have found striking about the conflict here is the lack of discussion. Even Fishman said he has avoided arguing his points with his fellow Jewish students, whom he characterized as often defensive. “I found it to be a bit of a waste of time,” he said.

Rachel Hale, a senior staff writer for The Daily Cardinal campus newspaper (and former Forward intern), said there’s no place on campus for “students who want to have dialogue, students who are pro-Palestine but anti-terrorism, Jewish students who are pro-Israel, but anti-Netanyahu.”

“From what I’ve observed,” she added, “it’s been very hard for Jewish students who feel like they might not feel super strongly in one direction to find that in-between gray space.”

Steinberger, the Hillel rabbi, said some progressive Jewish students have felt unwelcome in spaces they previously had considered their own, such as centers devoted to gender and sexuality, women’s studies and multiculturalism. Yet despite the number of students telling her how alone they feel, she said the attendance for group conversations at Hillel has been low.

When Steinberger speaks with students one-on-one, she said she tells them, “I’m pro-Palestinian.”

“I’ll say, ‘Look, it’s not a zero-sum game. You can be a Zionist or pro-Israel and feel very interested in Palestinian self-determination. You can be pro-ceasefire and be a Zionist,’” Steinberger said. “In these last many years, I’ve learned so much from listening to students about how they want to talk about gender and sexuality as being non-binary. And I want to give back to them the idea of, you know, the Israel-Palestine conversation as not having to be so binary.”

‘I feel fine here’

Fishman, the kaffiyeh-wearing Jewish student, offered his own nuanced view. “I wouldn’t consider myself a Zionist,” he said. “At the same time, I wouldn’t say I’m completely anti-Zionist, I do think that there should be a Jewish homeland, but I believe that the form in which it exists now is far from what ideally should exist.”

One consequence of this relative lack of argument is that the on-campus temperature remained milder than at the schools dominating the headlines. Even when more than 100 Jewish students gathered on a corner of Library Mall one night during the first week of the encampment, they didn’t engage with the protesters camping out on the other side of the lawn. Instead, the Jewish students waved Israeli flags, sang songs such as “Hinei Ma Tov” and danced the hora.

“My mom sees things from other campuses, and that makes her feel really scared, and I think it kind of surprises her when I say, ‘Honestly, I feel fine here,’” Hale said.

“As a Jewish student on campus, who’s covered this as a student journalist and talked with event organizers and protesters, I feel extremely safe on campus. I do not feel threatened,” Hale continued. “As a whole I choose to believe that these protesters are not antisemitic.”

One morning during my time at Madison, after storms had passed through the campus, Astrachan was back by the Library Mall fountain with another sign: “Bring Them Home Now” — a reference to the hostages Hamas still holds in Gaza. Hours later she posted a photo on Instagram of a yellow-vested “monitor” standing close to her “to make sure no one talks to me ofc!!”

That night, Fishman was making his mark, writing a chalk sidewalk message in Arabic and Hebrew translated as “Long live the fighters,” which he said was an Algerian cry of resistance against the French in the 1970s (though the Arabic phrase also is used in “Dune”). Fishman said he’d gotten the Hebrew translation from his cousin.

These two languages, at least, would be sharing this space.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO