Special ReportThe secret history and uncertain future of Students for Justice in Palestine

The group was founded as a voice of moderation — now it faces suspension and censure as it tests the bounds of student activism

Students participate in a protest at Columbia University last month, after the school suspended its chapters of Students for Justice in Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace. Photo by Getty Images

The protesters in Sproul Plaza, at the center of UC Berkeley’s campus, carried placards reading “Palestine Is In Our Hearts” and “Mercy To The Martyrs.” One person held an Israeli flag with a swastika at the center.

They spat at a group of Jewish counterprotesters, organized by Hillel, who were singing “HaTikvah,” the Israeli national anthem.

“We are your nightmare, Israel,” one demonstrator told the crowd. “Hamas is your nightmare!”

The year was 1995, not 2023. And instead of leading the protest, Students for Justice in Palestine had a small table off to the side, where a lone student told the local Jewish newspaper that the organizers of the rally, the Muslim Students Association, represented a “certain extreme.”

“We believe in peace coupled with justice,” the unnamed student added. “We oppose illegal settlements, not the peace process.”

Over the last three decades, Students for Justice in Palestine has evolved from that moderating voice at Berkeley into a sprawling network that is testing the boundaries of student activism, with at least four of its approximately 250 chapters suspended since the Oct. 7 terror attack on Israel.

The group’s national leadership initially celebrated the attacks as “a historic win for the Palestinian resistance,” although in the 10 weeks since it has focused on mobilizing students to oppose Israel’s assault on the Gaza Strip and mourning the thousands of Palestinians who have been killed.

Opponents say that its campus actions and vocal opposition to the existence of a Jewish state in Israel have created a hostile climate for Jews. The group’s leaders — some of whom are Jewish — reject accusations that its positions and rhetoric are inherently antisemitic.

But despite the club’s emergence as both a point of pride for supporters of the Palestinian cause and a lightning rod for criticism from Israel’s defenders, not much is publicly known about its history and how it operates.

Interviews with 14 current and former top leaders, and others close to Students for Justice in Palestine, tell the story of a network that was founded to press for Palestinian rights as a reasoned voice during the heady days of the Oslo peace process but has grown more strident as Israelis and Palestinians themselves have taken more extreme positions. While the current Israel-Gaza war has raised the network’s profile, and current leaders say it is “stronger than ever,” some former organizers raised concerns about the movement’s direction.

The founder of that original SJP chapter at Berkeley, for example, said in his first interview about the group in more than two decades that he has watched with apprehension as SJP flirts with support for Hamas.

“People just look at it and say, ‘There is resistance right now and we want to support that resistance,’” said the founder, Osama Qasem, who now runs an English-language bookstore in Jordan. “If you’re going to be an advocate for justice, you have to take a very moral position.”

But Qasem, who is not in touch with the network’s current leadership, said that is not his main concern. Instead, he shares the fears of other supporters of the movement who believe that the “vilification” of campus activists from some politicians, and well-funded pro-Israel groups eager to shut them down, will persist “no matter what” positions the group takes.

Feeling this pressure, many members of the network have started wearing masks and scarves to hide their identities at protests, and will only speak to the media on the condition they not be named. They fear that their personal information will be posted online and prompt harassment or thwart their job prospects, as has happened to some pro-Palestinian students at Harvard, Columbia and other schools since Oct. 7.

“It’s not normal that you have a student organizer face a paid truck going around campus with their picture,” said Hatem Bazian, who helped support the first SJP chapter as a graduate student at Berkeley in the 1990s and is now chair of American Muslims for Palestine. “There is no student organizing that could actually match or meet that.”

‘Bottom up’: Inside the network

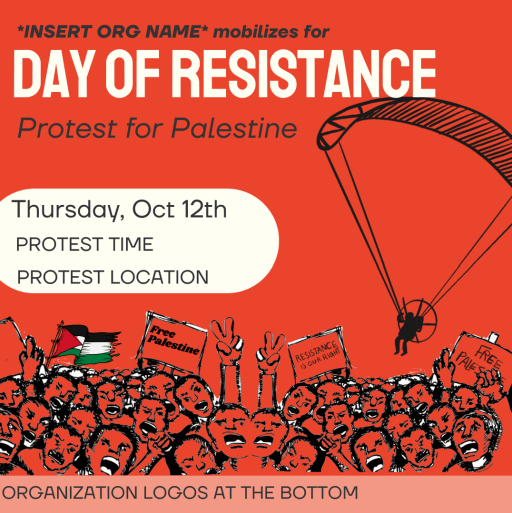

Five days after the Oct. 7 attack, Students for Justice in Palestine chapters across the country held a “day of resistance,” waving Palestinian flags and in some cases facing off against pro-Israel counterprotesters. This was followed by a series of walkouts, including one in early November that resulted in Columbia University suspending its chapter of SJP, saying the group violated school policy after hundreds of students participated in a “die-in” at the center of campus.

Brandeis banned its SJP chapter the same week because, as the university president said in a statement, it “openly supports Hamas.” Campus police broke up a demonstration organized by the banned club and arrested several students a few days later.

.@BrandeisU has cops arrest students for peaceful rally in support of Palestinians, including a Palestinian student. Shame on Brandeis and shame on the Waltham police. pic.twitter.com/DGRF6iVvsw

— Andrea Burns (@marudehar) November 10, 2023

Some SJP alumni have helped organize mass demonstrations like those that shut down bridges and public transit in New York City and other major cities in the weeks after the war began, but those protests were primarily organized by other organizations like Within Our Lifetime and Jewish Voice for Peace. SJP chapters remain focused on campus, where even a relatively small number of students can draw national attention.

The chapter at George Washington University, for example, was suspended last month after a few members used a projector to display pro-Palestinian slogans on the side of the campus library. Rutgers University suspended its chapter last week for what administrators called “disrupting campus life,” and two chapters at public universities in Florida are in limbo, with the American Civil Liberties Union suing to block the governor’s attempt to shut them down.

The group’s chapters across the U.S. and Canada, not all of which are active at any given time, are loosely connected by a coordinating body called National SJP, but it has no professional staff or national headquarters. This, and its opaque funding, have fueled claims that it is stealthy and connected to bad actors.

Some critics, including Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida, who is running for the Republican presidential nomination, have suggested that SJP is providing “material support” to Hamas, which would be illegal under federal law. Gerald Steinberg, president of NGO Monitor, which tracks groups critical of Israel, speculated that SJP might receive funding from Qatar.

“It’s not at all transparent, it’s very hidden, it’s very hard to discern what framework there might be,” Steinberg said.

Those involved in the movement said that these critics misunderstand the network and how it can have such a large impact without significant financial support.

National SJP is different from Hillel International, for example, which has an annual budget of nearly $58 million to support campus chapters, and whose activities often include student activism supporting Israel. SJP leaders said in interviews that the national group raises less than $100,000 a year to fund travel to a student conference and a national steering committee retreat, but that local chapters are typically financed by student government activity fees of a few thousand dollars on each campus.

“We don’t have mass funding backing us,” said R., a graduate student at an East Coast university and member of the national steering committee who spoke on the condition she be identified only by her first initial. “Our power comes from the bottom up.”

National SJP is not a registered nonprofit, so its financial information is not public. It accepts tax-deductible donations through the Westchester Peace Action Committee Foundation, a charity that serves as the fiscal sponsor for a number of pro-Palestinian organizations.

Fiscal sponsorship is an arrangement in which one nonprofit accepts donations and offers administrative services to a smaller one. Similarly, the pro-Israel group Alums for Campus Fairness is sponsored by the larger StandWithUs.

The arrangement makes it hard to discern SJP’s finances. WESPAC, which did not respond to repeated inquiries, sponsors more than 20 organizations and is not required by the IRS to disclose how much of its roughly $1 million annual budget represents money raised for National SJP.

The steering committee is made up of 20-25 volunteers who provide informal support to chapters around the country and organize an annual conference. Two of the current members are Jewish. Members, a mix of current students and recent graduates whose identities are not made public, remain until they choose to step down.

There is no formal affiliation between the national leadership and individual chapters, some of which go by other names, like the Palestine Solidarity Committee at Harvard. National SJP communicates with the local groups through an email list, Instagram messages and Signal, the secure-messaging platform, to run surveys gauging chapter needs, help new chapters get started and occasionally mediate disputes.

National SJP can pressure clubs to conform to its set of “core principles”: anti-Zionism, anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism and anti-normalization, which refers to the group’s opposition to working with Zionist organizations. And the group is also broadly aligned with the American left, including its support for the Black Lives Matter movement and skepticism of capitalism. It refers to the U.S. and Canada as “occupied Turtle Island,” referencing an indigenous term.

But national leaders say there’s nothing they can do to stop a chapter that does not abide by these principles from using the SJP name.

‘Time for peace’: The origins of Students for Justice in Palestine

Many critics of Students for Justice in Palestine tell a muddled story about its history, variously placing its founding in 1996, 2001, or even later. But almost all of these extensive dossiers place one man at the center: Hatem Bazian.

Bazian, who is now a lecturer at UC Berkeley, has been active in Bay Area campus politics since the 1980s, and founded American Muslims for Palestine in 2006. He was a graduate student at Berkeley at the time and has sometimes described himself as a co-founder of SJP.

In an email, Bazian said he was “the spokesperson and voice of Palestine and Palestinians on campus” in those early days and put SJP “on my organizing shoulders and brought them into the center of progressive networking on campus and nationally.”

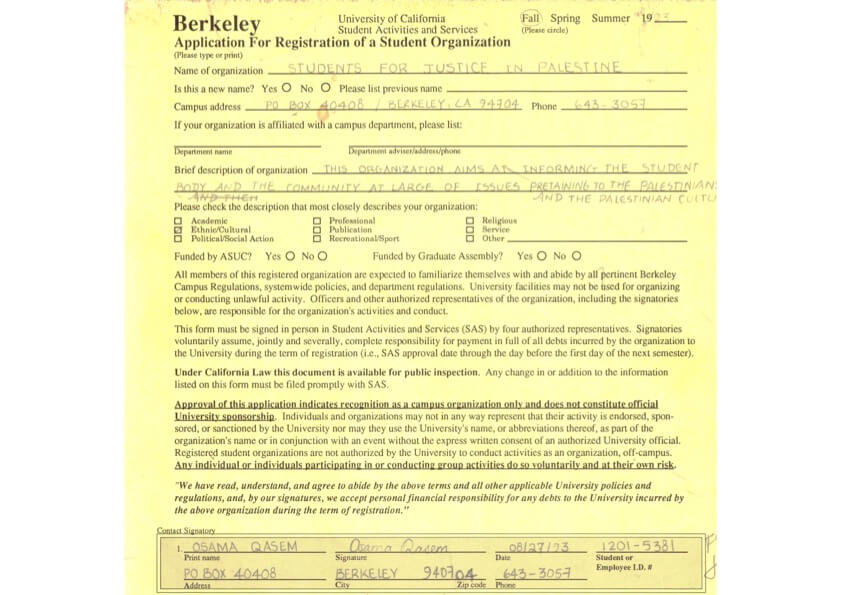

Qasem, the Palestinian-Jordanian bookstore owner, said that he, not Bazian, actually created the group in 1993, shortly after arriving at Berkeley to pursue a doctorate in industrial engineering. The following year, he said, he and three female Palestinian students incorporated it as an official club.

A brochure from that time described the club’s goal as informing “students and humans about the sad plight of Palestinian people.” In the spring of 1993, it co-sponsored a forum on “Israeli-Palestinian peace and social justice” alongside Berkeley Hillel and a group called the Progressive Zionist Caucus.

Shortly after Israeli and Palestinian leaders signed the 1993 Oslo Accords in front of the White House that fall, a member of the fledgling club named Tarek Elyadi wrote an opinion article in The Daily Californian expressing relief at the agreement.

“What are the alternative options? Have we forgotten what we are capable of doing with wrathful armies and deluded leaders?” Elaydi wrote. “It is time for peace.”

It was a contentious time for Palestinian activism in the diaspora.

Campus organizing had begun to grow following Israel’s 1973 war against Egypt and Syria, generally routed through the Organization of Arab Students, which was affiliated with Marxist and socialist factions of the Palestine Liberation Organization. There was also the General Union of Palestinian Students, which operated on dozens of campuses through the 1980s and had close ties to Palestinian leadership in the Middle East.

But during the 1990s, GUPS broke down over infighting. One student at a community college in Chicago recalled trying to vote for the leadership of his club in 1993, only to learn that a larger chapter at a nearby university controlled the outcome.

“It was like organized crime the way the territory was divided up,” said the student, who was quoted anonymously in an academic study of Palestinian activism in Chicago. “This guy takes my ballot before I even walk into the room and he scribbled something on it in Arabic.”

At the same time, as in the Sproul Plaza demonstration, some radical members of religious clubs like the Muslim Students Association expressed open support for Hamas, which at the time was a burgeoning Islamist movement from Gaza that found little favor among leftists.

Qasem said that he had a different idea: an independent student group free from political factionalism and religious influence. It was an unusual idea at the time, and he said Arab and Palestinian faculty at Berkeley expressed misgivings.

“There was always suspicion — ‘Who is behind this group?’” Qasem said. “They couldn’t appreciate that a group can be formed that has no backing and that it just came out of the minds of a few students.”

In its early years, SJP became increasingly critical of the peace process. Qasem, for his part, said he was always skeptical of the Oslo Accords and the club once hosted a debate between him and Elyadi, who had written the op-ed supporting Oslo, over whether the agreement deserved Palestinian support. By 1996, SJP was holding rallies at Berkeley decrying “Israel’s state terrorism” and America’s “shameful complicity.”

Qasem also recounted extended conversations with a group of Jewish students who would go on to found Jewish Voice for Peace. While that organization is now anti-Zionist, at the time it was critical of Israeli policies toward the Palestinians, not the existence of the state.

“We were considered far-left,” said one of those students, Rachel Eisner, who recalled talking with Qasem about things like how to share Jerusalem as part of a two-state solution.

By 1999, though, Qasem said the Berkeley group — at the time the country’s only SJP — could not muster the four students required to maintain its official club status, as issues like U.S. sanctions against Iraq began to eclipse the Palestinian cause.

‘Spread like wildfire’: The club’s rebirth

Palestinian activism heated up again in the fall of 2000 when Ariel Sharon, the Israeli opposition leader at the time, led a right-wing delegation to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Many describe the incident, which angered Palestinians around the world, as the spark for the Second Intifada.

At Berkeley, dueling communist organizations tried to use the crisis to recruit students. “You had one person saying, ‘This is a Marxist issue, Palestinians are against capital,’” recalled Will Youmans, a law student who had just arrived on campus after finishing his undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan. He was unconvinced.

Qasem, for his part, was busy with his work sequencing DNA at a Berkeley lab. But he had reactivated Students for Justice in Palestine that summer after its year of dormancy and agreed to hand off leadership to Youmans.

Bazian, who also runs a Muslim liberal arts college in Berkeley, had remained a constant presence on campus throughout this time. Youmans knew him primarily as a leader of the Muslim Students Association, which held occasional protests against Israel but was not focused on politics. Youmans thought Bazian might be able to draw more religious students into SJP.

“We were all leftists,” said Youmans, who is now a professor of media studies at George Washington University. “We used to party — we sat around and drank; it wasn’t very socially inclusive for the Muslims.”

The group tried to cast a wide net: Among its five new leaders were an atheist, a Jew and two Christians. The club also drew Marxists and anarchists itching to get arrested for civil disobedience. It was racially diverse, with white, Black, South Asian, East Asian students and others. One student, Youmans recalled, joined after his girlfriend, a strong supporter of Israel, dumped him for reading Edward Said, the Palestinian literary critic.

It didn’t take long for the revived club to attract attention. They did stunts, like creating a faux Israeli military checkpoint in the middle of campus where they harassed student actors posing as Palestinians in the West Bank.

And starting in spring 2001, Berkeley SJP called on the university administration to divest from Israel, mirroring a similar tactic directed at South Africa during apartheid. It was an idea that had grown out of the San Francisco office of the Arab American Anti-Discrimination Committee, which Qasem had helped form in the late 1990s.

‘Cunning and sneaky’: Some early actions rattle Jewish students

From the club’s reactivation in 2000, SJP almost always featured some Jewish members, and there were moments of warm relations between the group and the mainstream Jewish community on campus. In 2001, members joined a mostly Jewish vigil after a student participating in a Simchat Torah celebration on campus was beaten by three men chanting “Heil Hitler” and making Nazi salutes.

But its relations with Jews on campus were often tense, especially after 9/11, when Arab and Muslim students, especially those protesting Israel, faced new scrutiny, and complaints that they were creating a hostile environment for Jewish students.

In February 2002, Berkeley’s SJP held a conference on divestment at the law school, which is across the street from the Hillel building. Students stood outside the two buildings glaring at one another.

“When I walked into the courtyard, I heard someone say they were only letting in people with conference badges," Yasmin Sigel, a Jewish student, told a reporter at the time. "This is a public building, not PLO headquarters."

Later that year, SJP commemorated a 1948 conflict in which Zionist paramilitary forces killed more than 100 Palestians in the village of Deir Yassin. It overlapped with a quiet vigil being held for Yom HaShoah, the day of remembrance for Jews killed in the Holocaust. Pro-Israel students jeered speakers at the Deir Yassin event, including the child of a Holocaust survivor. Meanwhile, a Berkeley man who came to support SJP told a reporter that Jews were like pedophiles.

The prior year, the club had occupied Wheeler Hall, a central academic building on campus, which led to 32 arrests and the club’s suspension by the university. That event alarmed Jewish students after one Black speaker veered into antisemitism far more blunt than the rhetoric that has sparked ire at campus demonstrations since Oct. 7.

“Jews are born cunning and sneaky,” the Jewish Bulletin quoted him as saying. “African-American leadership in this country has been co-opted by the Zionist pocketbook.”

Youmans blamed comments like that on members affiliated with the Nation of Islam, along with Berkeley’s freewheeling climate. “Today I think there would be a lot stronger condemnation of those kinds of stereotypical statements,” he said. “There’s a lot more conscientiousness now.”

‘Super spontaneous’: The birth of National SJP

The controversy led to publicity. Youmans kept a running tally: The New York Times, CNN, CBS, MSNBC and NPR all came calling, and the original Students for Justice in Palestine began hearing from students on other campuses who wanted advice on starting their own chapters.

“SJPs grew like wildfire,” Youmans recalled. But there was little infrastructure to support the growing network — in fact, there was no network at all, he said, just a growing number of conferences that tried to draw students from across the state and country.

And there were disagreements, especially between students on the East Coast who favored a two-state solution and more radical activists based in California. “Everyone would just come and argue and disagree and go back to their campuses,” Youmans said.

Nearly a decade later, SJP chapter leaders needed more support. Dina Omar, who graduated from Berkeley in 2009, said she saw hostility grow toward members of SJP during her time on campus. One article depicted a friend of hers as a fan of Hamas, she said, despite the fact he was a proud atheist raised Christian.

“It felt like upside-down world,” Omar said in a recent interview. “There was a deluge of disinformation about who we were.”

Omar said she found like-minded activists at four conferences held in 2009 and 2010: a Campus Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions Conference at Hampshire College; the American Muslims for Palestine convention, which featured a student track; the U.S. Social Forum; and one in Qatar organized by Al Fakhoora, a nonprofit promoting education for refugees, including Palestinian children. She began to collect email addresses.

Soon she had a list of 36 students, and they planned a national gathering through a series of conference calls. “It was super spontaneous — I don’t know how to explain it,” said Omar, who is now working on her dissertation in anthropology at Yale. “It kind of willed itself into fruition.”

The group became National Students for Justice in Palestine, and created the steering committee. There were no votes and the members tried to operate through consensus, Omar said; they jokingly described it as a “do-s***-ocracy” — whoever took on a task, like booking rooms or picking a food vendor, was trusted to make the decision.

The first national conference took place in 2011 at Columbia University, where Omar was a graduate student at the time. Around 400 students attended. Local chapters were encouraged to fundraise for travel expenses, and Omar said that both American Muslims for Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace — which established a campus presence in 2010 and now has around 50 chapters — chipped in to cover flights for some of their members.

W., who was also at Columbia then and helped organize the conference, said that steering committee members were initially just focused on planning the gathering. But the large group that attended then had questions about how to hold events like Israel Apartheid Week and recruit speakers. Organizers realized that it would be useful to turn the steering committee into National SJP to help students with these questions year-round and plan future conferences.

Several advocacy groups have sought to tie the network, and especially its national leadership, to American Muslims for Palestine, saying that AMP either funds National SJP or was instrumental in its creation. And in an interview, Bazian recounted traveling the country both before and after he created AMP encouraging students to participate in Palestinian activism. But Omar said that part of the goal of creating a national network led by students was to preserve the same independence that Qasem had originally sought when creating the first SJP chapter at Berkeley.

“We were like, ‘This isn’t an anarchist, socialist thing, this isn’t a Muslim thing,’” she recalled. “The idea was to curtail some of that identity-based organizing that was really prevalent in the late ’90s and early 2000s.”

She said SJP chapters often include as many Jewish members as observant Muslims, as well as Palestinian Christians; they also draw those with no ties to the Middle East.

‘Wow, that was a bad move’: Questions over recent tactics

The lack of a formal structure supporting SJP means there are few guardrails around who participates in the network and what political positions they advocate. Omar recalled trying to deal with members who refused on principle to lobby elected officials, for example, and others enthralled by the cultish ideology of conspiracist Lyndon LaRouche.

“You come across a lot of crazies,” she said. “You try to hold a middle ground, and try to represent a kind of plurality of opinion, and try as hard as you can to push away the people who are going off the deep end.”

Since it is decentralized, supporters say, what someone does at an individual campus protest should not be held against everyone who participates in Students for Justice in Palestine.

Indeed, SJP chapters have shown a range of positions in the aftermath of Oct. 7. At Emory and the University of Florida, members mourned the death of Israeli civilians. But a club leader at George Washington University suggested there was no such thing as an Israeli civilian, and the Columbia chapter hailed the attack as a “counter-offensive against their settler-colonial oppressor.”

On the day of the Hamas attack, the national network sent a “toolkit” celebrating the violence to chapters around the country and encouraged them to hold a “day of resistance” on Oct. 12.

While Israelis and many Jews in the U.S. were cataloging a litany of horrors committed by Hamas, the toolkit celebrated the fact that Palestinians had broken through the barrier between Gaza and Israel and struck at “the very foundation of Zionist settler society.”

“This is the first time since 1949 that a large-scale battle has been fought within ’48 Palestine,” was one of the messages the toolkit suggested chapters use. “The zionist entity built a massive technological barrier to imprison Gaza that the resistance neutralized in hours.”

Steering committee members have since steadfastly refused to discuss the toolkit. It sits at the center of a legal dispute in Florida over whether two chapters at public universities in the state, and National SJP, provided “material support” to a terrorist organization, namely Hamas. Lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union sided with SJP, arguing that political speech is protected by the Constitution and cannot be considered illegal support for a terrorist group.

But the toolkit has remained a flashpoint: the Anti-Defamation League cited it in letters calling on nearly 200 colleges and universities to investigate their SJP chapters.

Some former leaders in the club worry that the rhetoric in the toolkit, and other recent actions by current steering committee members, make it easier for critics to claim SJP supports terror.

“Sometimes you get people who are doing things in super strategic, smart, principled ways and sometimes you don’t,” said W., who helped create the first national steering committee as a graduate student at Columbia. “Sometimes they do things now that I’m just like, ‘Wow, that was a bad move.’”

But Omar said she sees no meaningful shift in the network’s politics over the last two decades.

“I don’t know that they’re any more radical than we were,” Omar said. “Maybe more visible.”

Visibility is generally a good thing for activist groups. It’s a way to spread your message to the masses and draw new members. But the increased attention has also led pro-Israel and right-wing groups to disparage SJP’s work and harass its members.

S., a Jewish member of the national steering committee who spoke on the condition that only his first initial be used, said that he had received death threats and that his parents' private information had been publicized. “There have been scary moments,” he said.

Bazian, who has called for more civility on Berkeley’s campus during the current conflict, said the national attention has turned college students into political pawns.

“They’re all trying to catch that moment — not to guide the student in his young age, but to score a major point and get it into a hearing in Congress,” he said.

‘Stronger than ever’: Student leaders remain defiant

“The past eight weeks we are just witnessing a full-on genocide by Israel and that’s what we’ve been focused on,” S. said. “I’ve heard people say, ‘I don’t agree with your rhetoric on this but I still support your cause.’”

Despite the suspension of at least four chapters, several leaders said, more people have been turning out for protests. “We are stronger than ever,” said R., the psychology student on the steering committee.

Qasem, the original Berkeley founder, said he understood the toolkit’s celebration of Oct. 7, at least as it applied to the attacks on Israeli military outposts that occurred alongside the massacre of civilians.

“Was there something impressive about it? About people who were put under siege being able to launch such an attack, in terms of military means?” Qasem asked. “That part was lumped together with everything that was committed on that day.”

But he is worried that anger over Israel’s increasingly brutal violence against Palestinians and the lack of an obvious alternative is pushing the Palestinian solidarity movement into the trap of supporting Hamas. And that this could turn off potential supporters.

“I’m sure there are a lot of people — including Jewish Americans — who are standing on the sidelines, and don’t feel that they can belong on either side,” Qasem said. “I want the side we represent to be more welcoming.”

Some current members of SJP say that is easier said than done.

Shortly after National SJP was founded, it embraced the principle of “anti-normalization,” refusing to work with even liberal Zionist groups like J Street. Similarly, Hillel International banned its affiliates from working with anti-Zionist groups in 2010. Canary Mission, an online blacklist that includes many members of SJP, went live eight years ago.

The network’s current leadership believes that there is no version of the toolkit, or any script activists could use during campus demonstrations, that would blunt the backlash. For example, the University of Florida chapter’s statement about Oct. 7 included an expression of mourning for “the loss of innocent Palestinian and Israeli civilian life,” but DeSantis still tried to shut it down.

And so organizers expect the death threats and doxxing — which is sometimes condemned by mainstream pro-Israel groups — to continue regardless of their rhetoric. They think the legal pressure, too, including chapters being shut down, will continue.

“We will be attacked no matter what,” R. said of the network’s growing roster of opponents. “The core of what they’re attacking is Palestine.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO